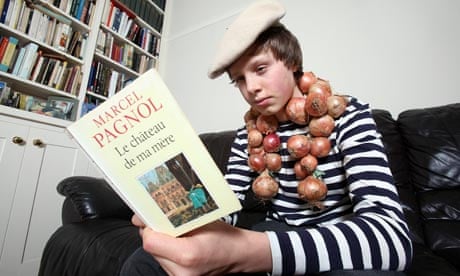

Alex Rawlings was a language teacher's dream. He fell in love with languages when he was eight and learned Greek, then German, then Dutch. Now, an undergraduate at Oxford, he is the UK's most multilingual student, speaking 11 languages. So what's his secret?

"I remember seeing people on the beach in Greece when I was a kid and not being able to talk to them," says Rawlings. "I thought it'd be nice to be able to talk to anyone in the world in their language. That has always stayed with me."

Such enthusiasm is rare: a report by the British Academy this year found there was a growing deficit in foreign language skills. Increasingly, children are choosing not to study languages beyond the compulsory stage – and only 9% of pupils who take French GCSE progress with it to A-level.

This week on the Guardian Teacher Network we are focusing on language learning. Every day, we'll have new pieces exploring topics ranging from changes to the languages curriculum in primary schools to how schools can encourage students to continue with languages beyond key stage 3. What teachers can do to boost engagement with language learning is going to be one of our main themes.

Language pedagogy has come a long way since the days when repetitive grammar-translation methods were regarded as the only way to learn. Today, task-based approaches are widespread in British schools, emphasising communication and the practical uses of language.

For Christelle Bernard, a French and Spanish teacher at St Gemma's high school in Belfast, these methods of teaching allow her to cast aside the textbook whenever she can. "You need a little bit of grammar, but my approach is much more topic-based, with as little grammar as possible," she explains.

Her task-based teaching embraces ideas ranging from lessons using computers to audiovisual and kinesthetic learning. She explains: "For instance, if I'm teaching pets, I'll bring in soft toys to use in the lessons."

"I hardly ever use a textbook – I use Twitter much more," she says, describing lessons where pupils discuss tweets written in French. "ICT allows them to collaborate with others. So they can work together, but it gives them a choice of medium. And because they know how to use computers, it creates a comfort zone where they can focus on the language."

Task-based learning typically involves an information gap: students may have to share knowledge to communicate effectively, or look for language rules themselves before re-applying them. It's an approach favoured by Huw Jarvis, a senior lecturer in the school of humanities, languages and social science at the University of Salford. He says: "We know that people learn better when they struggle to communicate – so that needs to be at the core of the kind of delivery and the methodology."

Some experts believe a conjunction of different ideas is the secret to learning and teaching. Michael Erard studied hyperpolyglots (multilingual speakers) in his book Babel No More. He explains: "They use a mix of methods, with a focus on accomplishing tasks, whether it's communicative tasks or translation tasks.

"What unites them is that they've learned how to learn, and each one has learned how he or she learns best. There is no uniform method or single secret that any one of us can duplicate."

But although Brits have long been famed for being lazy when it comes to learning foreign languages, the problem may partly lie in the number of hours of language education children are given. "We only give about half the amount of time to language teaching that they do in continental countries," says Richard Hudson, emeritus professor of linguistics at University College London.

A report by the European Commission in 2011 listed the UK joint-bottom in major rankings showing the number of languages learned in each country. National curriculum reforms set to be introduced next year – which will see foreign languages taught from the age of seven – may help, but figures show the UK has a long way to catch up with other European countries.

On average, pupils across Europe start learning languages between the ages of six and nine, but for many it starts even younger. In Belgium, learning starts in pre-primary education at the age of just three, and is compulsory until 18. And for children in Spain, Italy and Norway, language classes begin at six. Meanwhile, in Luxembourg, some students learn up to four languages in secondary education.

Bernard says that while methods of language teaching in continental Europe are often still grammar-based, it's the realisation that languages will be useful in later life that helps motivate students. "If we don't tackle the vocational side of languages, it doesn't seem to be that relevant to UK children," she says.

To continue the conversation, join us onlineon Thursday, 6-8pm, for a live chat on language teaching and learning. Our expert panel will be sharing teaching tips, creative lessons and discussing how to develop languages education in UK schools. theguardian.com/teacher-network

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion