James Wood

When I first read WG Sebald's great work, The Emigrants, I kept forgetting whether the book was originally written in German or English. Sebald wrote in German, but lived most of his life in Britain, and it was clear that he worked over the English so that it amounted almost to a collaboration with his translator. Sebald's prose belongs, mysteriously, nowhere. The enigmatic patience of the sentences, the pedantic syntax, the peculiar antiquity of the diction, the strange recessed distance of the writing, in which everything seems milky and sub-aqueous, just beyond reach – all of this gives Sebald his particular flavour, so that sometimes it seems that we are reading not a particular writer but an emanation of literature.

There's an undeniably bookish quality to Sebald's writing; despite his originality, some of his effects come from other writers. He takes his 19th-century Gothic diction from the Austrian writer Adalbert Stifter, and a fair amount of his obsessive extremism from the Austrian novelist Thomas Bernhard. (Sebald mutes Bernhard's suicidal clamour.) The effect is strange – Sebald seems both real and artificial, both alive and dead. In the essay published here, for instance, the author seems to be telling us directly about the time he spent on the island of Saint-Pierre. Yet the self-conscious pedantry – "during which time I passed not a few hours sitting by the window"; "an island with a circumference of some two miles" – makes the author a little distant, and we begin to wonder if the essay is a true account or a literary concoction spun in the study. As Sebald unfolds the story of Rousseau's tribulations ("a dozen years filled with fear and panic"), the essay seems, in its placeless antiquity, like one of Rousseau's own Reveries of a Solitary Walker, and suddenly it's not Rousseau's obsessive inability to stop thinking that is the theme, but Sebald's own obsessive inability ("the thoughts constantly brewing in his head like storm clouds"). In this way – and also, of course, through his use of photographs – Sebald was always asking us to reflect on how we access the past, how we rescue the dead, and how the writer performs that real, but necessarily fictional, reclamation.

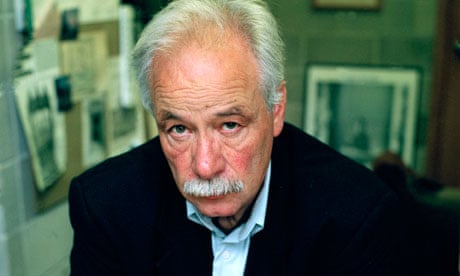

Iain Sinclair

I only set eyes on Max Sebald one time. We shared a descending lift in Broadcasting House, pressed back into our safe corners, silent. He impersonated what I took him to be – writer, walker, culturally burdened European – so beautifully that I wondered if this was an actor, a hireling. I had been reading in one of the broadsheets that morning how Sebald had agreed to give only one interview to publicise his latest project. Now the PR minder sent along by his publisher was running through the programme of the day's events: more radio, coffee conversations, lunch interrogations, readings.

One of the elements that drew me to Sebald was his interest, so elegantly glancing and oblique, in Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau, with his Confessions, his furious pedestrian surges across Paris, his long tramps out in the territory, arguing with memory, fixing the sins of the past, provided the quotation with which I launched my first book in 1970. "My thoughts were calm and peaceful; they were not heavenly or ecstatic. Objects caught my eye. I observed the different landscapes I passed through, I noticed the trees, the houses, and the streams. I deliberated at crossroads. I was afraid of getting lost, but did not lose myself even once. In a word, I was no longer in the clouds. Sometimes I was where I was, sometimes already at my destination, but never did I soar off into the distance."

From the start then, Rousseau catches the elusive essence of Sebaldian dogma: which is to be both elusive and precise, documentary and fabulous. Under the gravity of that silvered moustache, he was more English than the English, more alien.

Robert Macfarlane

In the too-short course of his writing life, WG Sebald remade the novel, and as he did so he also remade the travelogue. Walter Benjamin's observation that all great writers either create a new form or destroy an old one was only part-right in the case of Sebald, for he created multiple new forms. Certainly, almost no one seriously addressing the subjects of place and memory – whether in fiction, film, photography or academia – now does so from beyond Sebald's shadow (his writerly camp followers are legion, immediately identifiable by their melancholy lucubrations, the black-and-white photographs that stud their paragraphs, their flourished fetishes for skulls and for silk …). His four great "prose fictions" (Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn, Austerlitz), might appear regressive in their prolonged sentences, and their nested narrative structures, but really they opened fresh possibilities for the novel, especially in its engagements with trauma and atrocity. Sebald's seemingly passive prose was in fact – to borrow Marianne Moore's memorable phrase – "diction galvanised against inertia". I still remember reading The Rings of Saturn for the first time. It was – the dimming of light, the increase of pressure – like diving far down through historical water. The after-effects were with me for a long time; are with me still. Late in his life, Sebald wrote a short but fascinating essay on the work of Bruce Chatwin. "Just as Chatwin himself ultimately remains an enigma," Sebald remarked.

One never knows how to classify his books. All that is obvious is that their structure and intentions place them in no known genre. Inspired by a kind of avidity for the undiscovered, they move along a line where the points of demarcation are those strange manifestations and objects of which one cannot say whether they are among the phantasms generated in our minds from time immemorial.

Sebald could have been writing about his own astonishing and enigmatic books: haunted by phantasms who might be archetypes, polymorphous in their form, piebald in their appearance, travelling widely in time if not broadly in space, and inspired by an avidity for the undiscovered.

Will Self

WG Sebald, who died in a car crash in 2001, was an inspired essayist, quite as much as he was a novelist; indeed, I often think of his most achieved fictions – Austerlitz, and The Emigrants – as writing that tests the limits of both forms, blending them together at their margins with a kind of vaporous diffusion of their creator's lucidity, so entirely are the invented and the real fused together. This essay on the last years of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's life exhibits all of Sebald's strengths as a writer – and all of his strange, gnomic, secretive foibles. Ostensibly a straightforward account of Rousseau's exiled wanderings, it begins with his first glimpse, in 1965, of the Ile Saint Pierre in Switzerland, where Rousseau spent the first period of his stateless exile, and where he claimed – in his Reveries of a Solitary Walker – that he was happier than he had been anywhere else.

Sebald goes on to recount his own eventual landfall on the island in 1996, then employs this – the parenthetic of his own life – to consider the strange denouement and afterlife of the pre-eminent ideologue of the French revolution. It is a technique we are familiar with in Sebald's fiction: the author is very much present in these lines, and yet simultaneously absent. This is in keeping with Sebald's themes of exile and misappropriation, because, while he may be writing about another speculative thinker who lived 200 years before, as ever he is attempting to discover the hidden connections that bind human thought both to itself, and to the wider world.

Of course, what occurred between 1965 and 1996 for Sebald was his own exile: it was following the revelations of the Frankfurt Auschwitz trials in the summer of the year that Sebald visited the island (trials he witnessed firsthand, and which revealed to him the extent of his parents' generation's complicity in the Holocaust), and it was following this visit that the young academic took steps that led to his eventual domicile on another island, Britain, where he spent the next three decades at the University of East Anglia. Sebald allows this to lie beneath the text – a discoverable and psychic subtext; and just as he neglects to inform us of why Rousseau's paranoid and haunted final years should have had such a resonance for him, so this compulsively peripatetic and ambulatory writer also leaves off the list of distinguished writerly pilgrims to Rousseau's happy isle the greatest British walker-writer of them all, Worsdworth, who tramped all the way there in 1788, en route to his own liaison with revolutionary apotheosis.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion