Ernest Hemingway, author, exile, and Rimbaud-esque enfant terrible, fully understood the life-enhancing, horizon-broadening significance that Paris and its transplanted New York-owned newspaper, the English-language Paris Herald, held for nouveau-riche middle-class Americans.

In his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises, the first thing the autobiographical hero, Jake Barnes, does on his return to France from Spain is buy the Herald, as the present-day International Herald Tribune was then known, and read it in a cafe with a glass of wine.

Whether Hemingway intended it or not, Barnes struck a contagiously cosmopolitan pose that proved irresistibly attractive to the many would-be emulators who subsequently made the journey across the Atlantic.

For generations of Americans travelling to Europe before, during and after the two world wars, swapping the competitive, tight-laced rigours of the materialist, capitalist, God-fearing USA for the sophisticated languor, louche-ness and chic of the French capital, the Herald reported, reflected and symbolised the quintessential experience of embracing foreignness, and specifically Frenchness.

It provided a link with home while reminding the expatriate of his or her daring plunge into the unknown, slightly dangerous culture of the Old World.

And it became the newspaper of glittering record for what Gertrude Stein, perhaps the original "American in Paris", dubbed "la generation perdue", the lost generation, which hailed from America's Gilded Age and came into its own during the first world war. Its denizens included F Scott Fitzgerald, Isadora Duncan, TS Eliot, Waldo Peirce and Alan Seeger as well as Hemingway himself.

Years later, in 1953, Hemingway was still propping up the bar at the Paris Ritz, where he was discovered drinking bloody marys by the Herald's humorist, Art Buchwald.

Hemingway denied a report that he had consumed 15 martinis in 45 minutes at the Dome cafe in Montparnasse. The great man told Buchwald: "First of all, I'd never do such a silly thing, and secondly, I'd like to see anybody drink a dry martini at the Dome."

The exchange was reproduced in a special supplement published on Monday by the International Herald Tribune (IHT) to mark its last day of publication under that name. From Tuesday it will be marketed as the International New York Times, reflecting its present ownership and, presumably, the New York title's desire to project itself as a more recognisable global brand.

Buchwald's anecdotes aside, the supplement unearths old opinion and editorial pieces, historic news reports and front pages, fashion shocks, scientific breakthroughs and fusty photographs of mostly forgotten icons and tyrants, and reprints several of the paper's consistently unfunny cartoons. All were published after the Herald opened for business in Paris in 1887 under the auspices of James Gordon Bennett, owner of the New York Herald.

Like newspapers in the digital age, the transplanted paper was made possible by revolutionary technological advances, including more efficient printing methods and improved communications stemming from the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cables in 1858.

At the same time, according to Charles Robertson, author of a history of the paper, new audiences were being created by the rapid development of steamship travel and the advent of a new class of wealthy Americans eager to discover the Europe of their forebears.

In an editorial for the last edition, the IHT's Serge Schmemann argues bravely that the rebranded paper will remain vital and relevant because "we still need trusted reporters and editors to sort out the vast waves of information sweeping this chaotic world of ours. We need those first rough drafts, the smart commentary, the impartial news, to function in these times."

Not everything was smart, of course. To its credit, the IHT reproduces a May 1932 editorial that bemoans the lack of a strong fascist movement in America. It declares: "The hour has struck for a fascist party to be born in the United States."

Seven years later, reporting the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, the paper's tune changes: "The madman has unsheathed his sword, with Poland as his first victim."

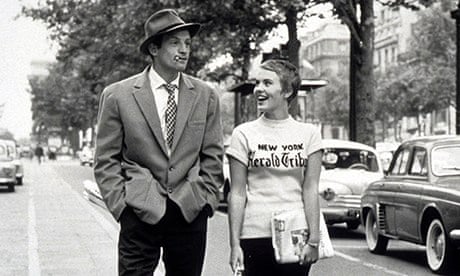

Eye-catching photographs include one of Andy Warhol sitting in Venice in 1977 reading the "Trib" – an unwitting tribute to Breathless, the 1960 film by Jean-Luc Godard that features an American student who takes a job selling the paper on the streets of Paris. Others show Adolf Eichmann at his sentencing in Israel in 1962 and Fidel Castro in full revolutionary fig in 1957. In 1931, but it could be 2013, Walter Lippmann discusses Gandhi's non-violence doctrine and deplores the way Americans, "who want peace but no responsibility", have abandoned a global peacemaking role.

Other reports and photos from the IHT archives record inspirational individuals of different stripes, including Simone de Beauvoir, Greta Garbo, Grace Kelly, the Beatles, and Martin Luther King, in Oslo in 1964 for his Nobel peace prize. One brief item from 1911 sums up the sort of journalistic dedication the rebranded paper will hope to maintain. It concerns a railway accident in which one of its reporters was injured. The reporter, who gets no byline, is quoted as saying: "Please ring up my paper and tell them there is a big story here. I'm sorry I cannot work on it myself." Then he died.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion