1) What’s the problem?

There are 46,139,900 voters in the UK. But getting all of them on to the electoral register isn’t easy.

Labour has claimed there are 950,845 fewer electors now than there were in last year’s registers and could miss out on voting on 7 May. The data comes from 373 local authorities across England and Wales.

That’s almost 1 million voters who have dropped off the electoral roll.

2) Are young voters at greater risk?

There is a correlation between areas of high student population and low electoral registration, according to elections watchdog the Electoral Commission.

Labour warns that many of the missing voters include young people, particularly students who are likely move more frequently, rent from a private landlord, and less likely to have an up-to-date record on the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) database.

The party blames the missing voters on the coalition government’s “hasty introduction” of electoral registration reforms in the past 12 months.

3) How has electoral registration changed?

In June 2014, a new system was introduced allowing each person to register their vote individually. For the first time ever, the electorate can register online.

The individual electoral registration (IER) system replaces the old system in which one person – traditionally the head of the household – was responsible for registering the votes of everyone else who lived at the address.

Campaigners described household registration as Victorian and there was a perception that this system was vulnerable to fraud. The shift to individual registration is the biggest change to the electoral registration system in 100 years.

But it means voter details have to be transferred to the new register.

4) How are voter details transferred to the new system?

Existing voter details are checked against the DWP database or local data. If there’s a match the voter details are “confirmed” – and then automatically transferred to the new IER system and sent a letter. The transfer of current registered voters in England and Wales to the new electoral registration system began last summer, while the new system went live in Scotland in September 2014.

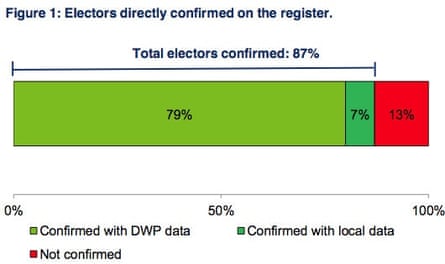

- So a total of 42.4 million electoral register entries were sent for matching against the DWP database.

- About 36.9 million electoral register entries – 87% of the total number of electoral records – automatically transferred to the new system during the live-run since June 2014, according to latest report by the Electoral Commission.

- However, it seems as though 5.5 million existing electors had not been automatically transferred. This is 13% of the total number of electoral records.

- But that’s not all. Between the matched and non-matched groups, there are 7.5 million people who were not registered at their current address (but may still be registered at a previous address), or may not be on the register at all.

Voters whose details could not be transferred automatically need to re-register. There has been a drive to get more people registered in recent months.

Those who have fallen off the electoral roll have until 20 April to register in order to be able to vote in the 7 May general election.

But it’s important to note that voters on the register before the transition will stay on the December 2014 register and will not lose their vote at the 2015 general election, even if records have not been confirmed. But an unconfirmed voter will drop off the register if a new application is not made by December 2015.

By January 2016, the transition to IER will be complete, according to the government.

5) What about students?

Since the electoral reforms, 100,000 registered voters have been lost in London, 25,000 in Cardiff, 20,000 in Liverpool and 18,000 in Newcastle, according to Labour’s calculations.

Ed Miliband, the Labour leader, has claimed that the greatest decline in the number of registered voters are in cities with high student populations such as as Cardiff (-8.9%), Liverpool (-6.4%), Newcastle (-9.0%), Southampton (-7.9%), Leicester (-5.6%), Nottingham (-6.4%), Brighton (-10.5%), and Hull (-6.6%).

These are also areas where Labour hopes to get the most gains from the Lib Dems and Tories.

One of the key components of the reforms is that universities and colleges can no longer block register students living in halls of residences to vote, which Miliband calls a “democratic scandal”.

6) What about people who have just turned 18?

It looks as though only 52% of people who turn 18 during the latest electoral register – “attainers” as they are called – were transferred to the new individual electoral register during the live-run. This is down from 86% of attainers being included in the 2013 register, according to the Electoral Commission.

7) So what’s being done to make sure young people can vote?

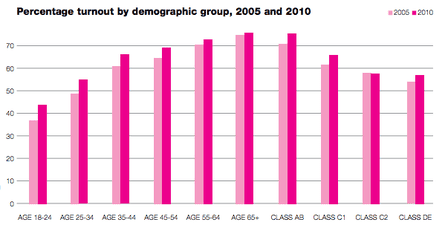

In 2010, just 44% of people aged 18 to 24 voted in Britain’s general election, compared with 65% of people of all ages. There are many factors to this, such as not identifying with the main parties or not registering to vote.

So in efforts to improve voter engagement, the government made £4.2mn available to maximise registration during the transition to the new IER system.

On top of this, last week the government announced £9.8mn in extra funding. Sam Gyimah a Tory cabinet minster, said: “The government today will give local authorities the resources they need to make sure they can invite people to register to vote.”

On the other hand, parliament has just rejected a proposal to project an image on to Big Ben of a vote going into ballot box to draw attention to National Voter Registration Day on 5 February without explanation.

Graham Allen MP, chair of the parliamentary political and constitutional reform committee, said this decision makes parts of parliament look like it’s run by “old farts”.

He said: “With more people not voting than voted for both main parties added together in 2010, our democracy is in crisis. We need new and exciting ways to encourage people to register to vote.”

8) What are campaigners saying?

Well, campaigners such as Bite the Ballot and the National Unions of Students (NUS) have been calling on the government to make voter registration as easy, engaging and accessible as possible during the transition to IER.

There’s been a huge drive by student organisations, and the NUS has even set up a general election hub that enables students to register and see who the candidates in their constituency are.

Students, according to the NUS, “hold the key to the next general election” and the body said that its recent poll shows that 73% of students that they represent were registered to vote by the end of last year, compared with only two-thirds in February 2014. Yet only 4% of students strongly identify with any political party.

The impact of student voting is that it could swing the result in just over 10 constituencies, according to thinktank the Higher Education Policy Institute.

9) Is it the same story across England and Wales?

No, there’s some variation in the transferring to individual electoral registration across England and Wales. It ranged from 59% in Hackney to 97% in Epping Forest. And in wards, the rate ranged from 7% in Oxford’s Holywell ward to 100% in Lancaster’s University ward.

10) What about the varying electoral sizes in different areas?

Yes, it’s true that confirmation rates alone don’t tell the whole story. For example, although Leeds achieved a 86% confirmation rate leaving it with 76,000 unconfirmed electors, Birmingham also had a high confirmation rate at 81% but with 143,000 unconfirmed electors. That’s a lot.