Why Parents Need to Let Their Children Fail

A new study explores what happens to students who aren't allowed to suffer through setbacks.

A new study explores what happens to students who aren't allowed to suffer through setbacks.

Thirteen years ago, when I was a relatively new teacher, stumbling around my classroom on wobbly legs, I had to call a student's mother to inform her that I would be initiating disciplinary proceedings against her daughter for plagiarism, and that furthermore, her daughter would receive a zero for the plagiarized paper.

"You can't do that. She didn't do anything wrong," the mother informed me, enraged.

"But she did. I was able to find entire paragraphs lifted off of web sites," I stammered.

"No, I mean she didn't do it. I did. I wrote her paper."

I don't remember what I said in response, but I'm fairly confident I had to take a moment to digest what I had just heard. And what would I do, anyway? Suspend the mother? Keep her in for lunch detention and make her write "I will not write my daughter's papers using articles plagiarized from the Internet" one hundred times on the board? In all fairness, the mother submitted a defense: her daughter had been stressed out, and she did not want her to get sick or overwhelmed.

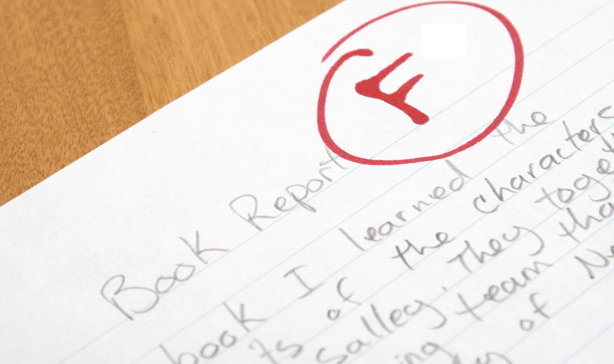

In the end, my student received a zero and I made sure she re-wrote the paper. Herself. Sure, I didn't have the authority to discipline the student's mother, but I have done so many times in my dreams.

While I am not sure what the mother gained from the experience, the daughter gained an understanding of consequences, and I gained a war story. I don't even bother with the old reliables anymore: the mother who "helps" a bit too much with the child's math homework, the father who builds the student's science project. Please. Don't waste my time.

The stories teachers exchange these days reveal a whole new level of overprotectiveness: parents who raise their children in a state of helplessness and powerlessness, children destined to an anxious adulthood, lacking the emotional resources they will need to cope with inevitable setback and failure.

I believed my accumulated compendium of teacher war stories were pretty good -- until I read a study out of Queensland University of Technology, by Judith Locke, et. al., a self-described "examination by parenting professionals of the concept of overparenting."

Overparenting is characterized in the study as parents' "misguided attempt to improve their child's current and future personal and academic success." In an attempt to understand such behaviors, the authors surveyed psychologists, guidance counselors, and teachers. The authors asked these professionals if they had witnessed examples of overparenting, and left space for descriptions of said examples. While the relatively small sample size and questionable method of subjective self-reporting cast a shadow on the study's statistical significance, the examples cited in the report provide enough ammunition for a year of dinner parties.

Some of the examples are the usual fare: a child isn't allowed to go to camp or learn to drive, a parent cuts up a 10 year-old's food or brings separate plates to parties for a 16 year-old because he's a picky eater. Yawn. These barely rank a "Tsk, tsk" among my colleagues. And while I pity those kids, I'm not that worried. They will go out on their own someday and recover from their overprotective childhoods.

What worry me most are the examples of overparenting that have the potential to ruin a child's confidence and undermine an education in independence. According to the authors, parents guilty of this kind of overparenting "take their child's perception as truth, regardless of the facts," and are "quick to believe their child over the adult and deny the possibility that their child was at fault or would even do something of that nature."

This is what we teachers see most often: what the authors term "high responsiveness and low demandingness" parents." These parents are highly responsive to the perceived needs and issues of their children, and don't give their children the chance to solve their own problems. These parents "rush to school at the whim of a phone call from their child to deliver items such as forgotten lunches, forgotten assignments, forgotten uniforms" and "demand better grades on the final semester reports or threaten withdrawal from school." One study participant described the problem this way:

I have worked with quite a number of parents who are so overprotective of their children that the children do not learn to take responsibility (and the natural consequences) of their actions. The children may develop a sense of entitlement and the parents then find it difficult to work with the school in a trusting, cooperative and solution focused manner, which would benefit both child and school.

These are the parents who worry me the most -- parents who won't let their child learn. You see, teachers don't just teach reading, writing, and arithmetic. We teach responsibility, organization, manners, restraint, and foresight. These skills may not get assessed on standardized testing, but as children plot their journey into adulthood, they are, by far, the most important life skills I teach.

I'm not suggesting that parents place blind trust in their children's teachers; I would never do such a thing myself. But children make mistakes, and when they do, it's vital that parents remember that the educational benefits of consequences are a gift, not a dereliction of duty. Year after year, my "best" students -- the ones who are happiest and successful in their lives -- are the students who were allowed to fail, held responsible for missteps, and challenged to be the best people they could be in the face of their mistakes.

I'm done fantasizing about ways to make that mom from 13 years ago see the light. That ship has sailed, and I did the best I could for her daughter. Every year, I reassure some parent, "This setback will be the best thing that ever happened to your child," and I've long since accepted that most parents won't believe me. That's fine. I'm patient. The lessons I teach in middle school don't typically pay off for years, and I don't expect thank-you cards.

I have learned to enjoy and find satisfaction in these day-to-day lessons, and in the time I get to spend with children in need of an education. But I fantasize about the day I will be trusted to teach my students how to roll with the punches, find their way through the gauntlet of adolescence, and stand firm in the face of the challenges -- challenges that have the power to transform today's children into resourceful, competent, and confident adults.