Can you hate part of yourself so much that you want to kill people like you? And is that a hate crime?

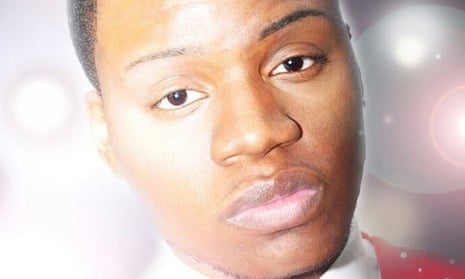

Those are the questions being whispered at gay bars, asked behind tears in family living rooms, and maybe even being answered by the police force here – on the other side of Missouri from Ferguson – after the shocking and complicated death of 22-year-old Dionte Greene, who was shot and killed on the morning of Halloween in his still-running car, possibly by a “straight” man who may have agreed to meet him for sex.

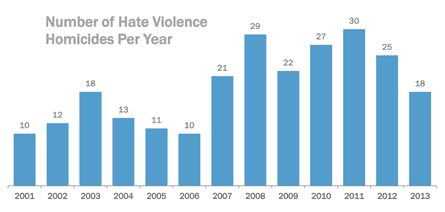

In the minds of Greene’s family and friends, there is no doubt that he was murdered because he was gay – probably, they say, by the man he decided to meet. But in the eyes of the law – or at least law enforcement – that man’s alleged sexual interest in Greene means this killing and others like it cannot be considered hate crimes. One human’s self-doubt can be the end of another’s life, and even with hate crimes on the rise across the US, that letter of our lethargic law means we’ll never know about violence we’re already not doing enough to prevent.

“My son ... he was quiet – not a problem child,” Coshelle Greene told me late last month, as a nation began to confront what justice looks like for young black lives lost too soon. “Being that he wasn’t a street person, and didn’t have enemies, I lean towards it having to be someone who was on the down-low or someone so against gay people that they would do this.”

Greene’s mother and many of the other people I interviewed in Kansas City fear that since Greene’s body was discovered in a low-income, high-crime area that is predominantly black, his case will merely be classified as another crime against a black person by a black person – rather than a modern kind of true crime against a gay man who was also black, by a man who may have been afraid of the truth.

And they should be worried, because justice vanishes too often with cases that force police departments and even the most progressive communities to consider victims who lived at the intersection of multiple sexual and gender identities – the complex people who are at a much higher risk of facing hate-motivated violence, or even perpetrating it.

Especially when you’re black. Especially when the cops would rather not check an extra box.

On 30 October, Dionte Greene finished work before midnight to attend a “turn-about” party, where people show up dressed as a different gender. But before the party, Greene had plans with some “trade” he had been talking to online, several of his friends told me. “Trade” is a version of “on the down-low” – terms used within black LGBT communities to describe a man who doesn’t “appear gay” but who engages in sex with men unbeknownst to his family and most of his friends. Trade is a man you don’t necessarily trust – more of a risk than many are willing to take.

According to friends who saw his private messages, Greene had been in correspondence online with this “trade” for some time prior to their meeting, as the man apparently tried to decide whether or not they should meet up. The “trade” was very much on the fence about having sex with men, according to accounts of these messages, and he very much did not want his sexual secret to be found out. But something changed, and the “trade” agreed to meet up that night, Greene’s friends said.

When Greene arrived at the pre-arranged meeting spot in a quiet residential area just miles north of his home, he was on the phone with a friend who could sense that Greene was a little nervous about the meeting. As they spoke, according to other friends with knowledge of this conversation, the man started walking towards Greene’s car. “He looks just like his Facebook picture,” Greene allegedly said.

Moments later, Dionte Greene’s friend heard yelling. The phone line went dead. And Dionte Greene ended up with a gunshot to the face in the driver’s seat of his car.

In a slowly increasing trend for American law enforcement, the Kansas City police department recently appointed its first LGBT liaison, Rebecca Caster, an affable, blond-haired, out-lesbian cop who’s proud to work for a “very progressive” city “that is willing to push the envelope and create change”. There have been no charges or arrests yet in the Greene case – the homicide investigation is very much still active – but Officer Caster still doesn’t necessarily see circumstances like the ones alleged by Greene’s friends: a hate-based sexual killing, spontaneous murder driven by identity politics as much as rage. Several of these friends have been interviewed by the cops, too, but the cops still won’t – can’t – call Greene’s killing a hate crime.

Even the most visibly gay cop in Missouri’s biggest city is not allowed to put this case in the class of crimes that, when acknowledged as they were with Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr in 1998, can actually help address the root causes of the very real violence that people are facing based on their identities, especially when they’re black and gay.

“If someone is actually engaged in ‘the act’, then these are not hate crimes,” Caster told me.

But according to the Kansas City Anti-Violence Project, which organized a meeting on 11 November between Greene’s friends and the police, Greene’s case is one of at least seven murders of LGBT people in Kansas City since 2010 – and three of those strike community leaders as eerily similar crimes of passion.

I pressed Officer Caster about the case of Henry Scott IV, who was stabbed and burned alive four years ago. Birmingham White pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter in the case in 2011 and was sentenced to 15 years, plus an additional seven on a weapons charge. Multiple people in Kansas City’s LGBT community alleged that White was Scott’s lover but that White never came out as gay and that he killed Scott to keep him from outing him. Officer Caster told me that Scott’s death was also never considered a hate crime – and so one bias-motivated killing got swept under the rug, instead of helping to prevent another.

“It was motivated by his fear of being out,” Caster said of White’s motive for the killing. “The thing is, hate crimes need to be, ‘I can’t stand the fact that you are gay so I am going to drag you behind a truck. I don’t know you, I don’t care.’”

It makes your stomach turn, hearing a cop so matter-of-factly say something like that. It’s enough to make you think that Dionte Green’s case might follow the same path: young black man murdered without the protocol to investigate the terrible, complicated bias potentially behind the whole familiar crime, nothing changes, another black man dies tomorrow.

A spokesperson for the KCPD told me on Monday afternoon that “savvy” detectives were on the case reviewing all evidence and that “some tips were received after the initial news reports”. But by the time that police work plays out, history may have already repeated itself again with the same tragic consequences.

The morning her son was shot and killed was Halloween, and Coshelle Greene had been “fussing at” Dionte through the walls of their ranch-style home, from a room away, about cleaning up around the house. When he didn’t respond, she checked the living room where Dionte had been sleeping since moving back home. But Dionte never came home on Halloween. So she called his phone, which went to voicemail.

And then came a knock on the door. “[I]t was the police and they asked me, ‘Does Dionte Greene live here?’” They didn’t tell her why – they just asked questions about the last time she’d seen her son, what kind of car he drove, if she had any photos of Dionte, like that. Questions about his sexuality never came up; they were never answered because they were never asked.

As the questions continued, Coshelle got flustered and finally refused to answer any more of them until the two officers told her that they had found her “baby”.

They had.

The last available hate-crime statistics from the FBI show that 46.9% of these reported crimes in the US were motivated by race and 20.8% were motivated by sexual orientation. They do not account for when race and sexuality overlap. In 2013, more than 2,000 incidents nationwide reported incidents of LGBT violence; of the 18 anti-LGBT incidents classified as homicides, 16 of the victims were people of color and 13 were transgender, and two-thirds were transgender women of color. That’s a lot of overlap – and that’s almost certainly an undercount, because police departments in places a lot worse than Kansas City aren’t all that interested in counting.

Hate crimes are crucially important to our broken criminal justice system. They differentiate from unbiased motivated crimes, and not just by reminding us, officially, that we do not live in some sort of post-racist or post-gay utopia. When the cops investigate and lawyers prosecute something as a hate crime, it teaches us quite the opposite: that we cannot afford to ignore systems like racism and homophobia – that we will not, officially.

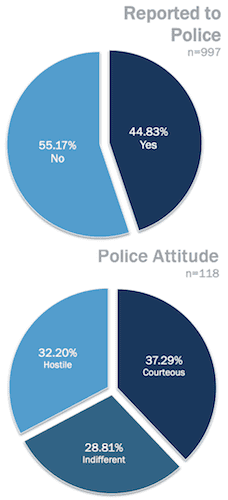

Hate crimes and bias-motivated crimes are some of the most underreported to police, right up there with sexual and domestic assault, even though they are so clearly based on the sheer hatred of someone for who they are – even though they should be reported the most. But even when hate crimes are reported, they’re often handled inappropriately, if not downright ignored.

“With biased crimes, it seems like pulling teeth to get them to check that extra box in the paperwork,” says Justin Shaw, executive director of the Kansas City Anti-Violence Project. “We hear so many incidents that happen and get labeled simple assault when there is an obvious hate component – it feels as if we are stuck in a paperwork cycle with people’s lives.”

Shaw suggests that many officers take a laid-back approach to filing cases like Greene’s – that they tend to skip marking any potential bias on police reports, because it is easier for cops to chalk up situations to “unfavorable neighborhoods” like the one in which Greene’s body was found.

If the aftermath of the very public killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson has taught us anything, it’s that cops should never default to their worst instincts when it comes to young black bodies in a “bad” part of town. That just makes it easier to keep chalking up the sidewalks, with the outline of another dead man.

The Kansas City police spokesperson told me Green’s death would be prosecuted as a hate crime if there is “enough evidence”, but even when cops do check the hate-crime box, a case tends to be imagined as an encounter between strangers. “When two people have a relationship and there is a grudge or jealousy or betrayal,” says Jack Levin, professor of sociology and criminology at Northeastern University, “then the court is reluctant to charge as a hate offense.”

The primary premise of hate-crime law, Levin explained, is determined by a “difference” between the victim and the suspect – by the very lack of a relationship. So when bias-motivated crimes occur between people who share an identity to some extent and know each other, prosecuting them as such becomes that much more difficult.

“Hate crimes are message crimes,” Levin says, “and hate-crime laws send a message back. They send a message to the perpetrator that we do not encourage or support him – that we don’t agree with his intolerance.”

Dionte Greene was 16 when he told his mother he was gay, and she blamed herself – for not allowing his own father or other potential role models to come around. “I wasn’t so much against it,” Coshelle Greene told me, sitting on the couch Dionte used to call a bed. “I just didn’t want it for mine. I just knew how society looks at it, and how it’s so frowned upon.”

Greene’s mother knew what the world thought of gay men – what it still thinks of us – and she knew that her son already had so much stacked against him as a black man trying to stay off the streets. Being gay was just another strike against him.

But Coshelle Greene didn’t turn her back on her son then – and she still won’t, even as police quietly continue their investigation and the case gets barely a few paragraphs on local television station websites. As its investigation continues, Greene continues to call the Kansas City police department several times each week to make sure her “baby” isn’t pushed aside – so that the police accept what Coshelle Greene already believes: Dionte was murdered because he was gay, and his murderer wasn’t sure if he wanted to be.

What breaks Coshelle’s heart even more is that not even Dionte – a quiet, smart, well-dressed kid whose mom made sure he went to school and church – could escape the same plight of so many black men in America who face such exorbitant violence from police and from their communities. The heartbreaking thing is that she has been made into just another mother who lost just another son.

Because there were already too many strikes against him.

“There is a lot of work to be done,” Officer Caster told me over coffee in the mostly white Westport neighborhood of Kansas City, about 10 miles from Greene’s home in the predominantly black southern part of town. “But I am excited about it. I am excited about bridging the gap between the police department and the LGBTQ community, but also ourselves.”

It’s a sentiment you hear more and more as same-sex marriage continues its roll across America. Many within the LGBT community are asking: OK, what can we do for ourselves next? But self-reflection isn’t productive when we don’t know who “ourselves” even are.

To be black and gay and transgender and poor, for example, is to be a more colorful rainbow, for sure. But each of those definitions of self multiplies the systemic violence attached to each of them – every extra sliver of the rainbow widens that gap between safety and danger.

It’s a gap that reveals how a law enforcement system can fail not just black people, but black people who are also gay – simply because cops can’t immediately start investigating hate crimes, even if they have immediate evidence about the sex lives of our Dionte Greenes.

It’s a gap that exposes homophobia as not just something that makes someone drag you behind a truck, but as a sickness that can make someone kiss and then kill – simply because someone didn’t want their secret to get out.

And it’s a gap that tells all of us we need to start checking those boxes. That is the work to be done.

Missie B’s is a gay bar that’s usually full of white people, but two Fridays ago, as the grand jury in Ferguson announced it needed another weekend to announce its decision, a couple dozen black LGBT people milled around watching a drag show.

“It’s been really tough,” said Star Palmer, a 34-year-old black lesbian woman, looking exhausted. “This shouldn’t have happened to him. Not Dionte.”

There are deep divides between the police and the large LGBT community in Kansas City, but also within the gay community itself. “These bars will maybe let us throw an event here or there,” Palmer says of nightlife in the city, “but we always have to be gone by 10 so the white patrons can have the bar back.”

So Palmer and friends throw club nights around town for black LGBT people who want a safe space – who need a place where they are welcomed, rather than having to meet up with strangers on late-night street corners.

Dionte Greene was a member of the House of Cavalli, a kind of second “family” of the type that has emerged especially within black LGBT communities – often to create support systems for people who have been rejected by their biological parents. (Members of the house attended the November joint meeting with police investigating the killing.)

Hooking up with “trade” is a hot topic in houses across the country – but the dangers of the trend often get left to whispers as faint as a police officer who would rather not find out if a homicide victim was gay.

“We need to educate the kids,” Palmer says – that it’s never a victim’s fault, that it’s OK to hook up with someone who’s unsure of his sexuality (“It’s a conquer thing,” she tells me), as long as you take the necessary precautions. Given the deep racial segregations in the LGBT community of this city and so many like it, leaders like Palmer and Korea Kelly, the mother of the House of Cavalli, need to lead in safely navigating a culture that is open about sex but protective about the potential risks of certain practices. Because American cops sure aren’t doing enough to lead.

As a transgender woman, Kelly knows all too well the potential violence people face when you’re LGBT and you’re having sex with someone who doesn’t identify with that community. “You’re playing with fire,” Kelly told me over lunch. “This is someone who is not cool with this, so you’re taking a chance. Yes, it could be death, [or] he could think, ‘Ah, he’ll just bop me’, or it could be more. You never know.”

As little as parents and police choose not to know about the sometimes dangerous subcultures of America’s gay community, trust me: this is not a black thing.

While the subculture of the “down-low” has predominantly been framed within the context of black men, trust me: having sex with men who don’t identify as gay is not a black thing. All sorts of men do it.

I have actively pursued men – black and white, young and old – who don’t necessarily identify as gay or bisexual. If you give it enough time, sometimes they engage on the “down-low”. And there is something about having a man choose you that fulfills the very self-hatred – deep down in many gay men – that homophobia seeks to maintain.

LGBT people grow up in a world that says “no” all the time. No, you’re not worthy. No, your desires are unnatural. And we hear a lot of this from men. So when a man does come to you and he’s willing to explore everything he has said “no” to for so long, many of us say “yes” to that man – even if he’s a murderer.

That totally natural instinct does not make the dangerous fallout from our complicated desires our fault – Dionte Greene is not to blame for his own death – but it does mean we need to account for the danger. It means that crimes of confused passion must be hate crimes, just like cases that involve someone being dragged behind a truck, as in Officer Caster’s banal fantasy of violence, because both have to do with being LGBT. The complex hate crime and its rulebook cousin are both motivated by the insidious ways in which homophobia still exists – that someone would rather kill than be outed or caught getting a blowjob from another guy in the front seat of his car.

That is what a “very progressive” city should do. That’s what “pushing the envelope” means. That’s what justice looks like to Coshelle Greene, a modern mother who rose above stereotypes and circumstances that have pushed so many other parents to turn their backs on people like her son.

Sitting there with Coshelle on the couch where Dionte slept, I thought about my own mother, who never cast me out of her own life, and how we both had mothers who loved us, Dionte and me, and families that took care of us, and how we as black gay men can do everything right – and still end up dead for being gay and black anyway.

- Comments will remain closed on this article.