Half-past noon in Burundi once looked the same each day. From the paved streets of the capital city Bujumbura to the countryside’s dusty roads, everyone stopped what they were doing, pulled out their phone, and tuned into the Radio Publique Africaine’s news program.

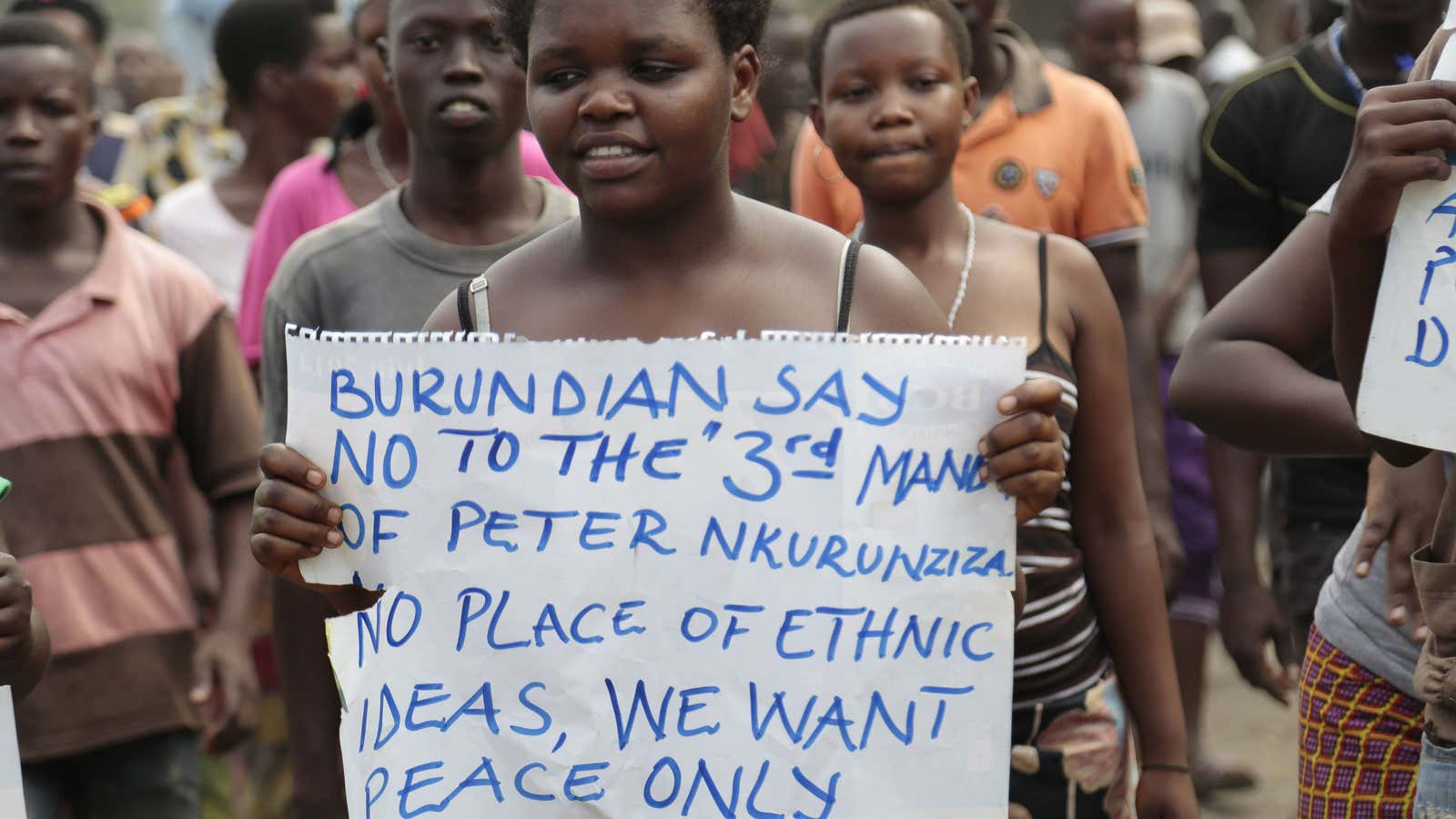

But since political unrest broke out in April, a government crackdown on independent press has left the country in a media blackout. Independent radio studios have been attacked, roughly 50 reporters have fled the country, and Radio Nationale–a government-run station which has denied protests are even taking place–is the only radio left broadcasting.

Until now.

A group of brave journalists–dubbed “SOS Medias”–has gone underground to broadcast the only independent news available in the country. And with military officers physically keeping them from their studios, they are turning to a new platform to broadcast the news: SoundCloud.

“Even if we could get into our studios, a lot of our equipment has been destroyed,” says one member of the team on the condition of anonymity due to security concerns. “The website allows us to continue to broadcast radio reports using whatever recording devices we have.”

The ten-person team formed after May 13th when a coup attempt announced on independent radio led to stricter media repression. The reports on their SoundCloud page range from minute-long interview clips to full-fledged news reports on the current unrest.

In one report a journalist details the recent closure of the office of Air and Border Police. In another, opposition leader Agathon Rwasa explains his qualms with the coming elections at a press conference, the clicks of photographers’ cameras echoing in the background.

There is a long tradition of repressive African regimes shutting down or curtailing the operations of privately-owned media outlets that voice opposition to the government of the day. However, the focus has always been on newspapers, radio and television. While there has been a shift of focus to try and block online social networks, many of these types of regimes still leave plenty of loopholes. SoundCloud, which has 250 million users a month, is predominantly a platform for sharing music but is also used for talk audio such as podcasts.

Limited audience

But SOS Medias’ SoundCloud broadcasts face a major obstacle: poverty. Roughly 68% of Burundians live below the poverty line, and while people can tune into local radio broadcasts using even the cheapest cell phones, few have the smart phones or Internet access needed to listen to the online reports.

“Right now SOS Medias is very limited to certain people, mostly the intellectuals in Bujumbura, who can access it,” says the SOS reporter. “So we’re trying to also post written reports on Facebook because more people use it.”

The difference in audience size between the two platforms is stark. Roughly 11,000 people follow their Facebook page while their SoundCloud reports typically attract only 500-1,000 listeners.

In the last few days the SOS Medias team has expanded their operations on Facebook, publishing feature-length articles in addition to regular news updates.

But after the government briefly blocked access to social media sites including Facebook in April, journalists fear another shut down as elections approach in July. And though SoundCloud was not blocked during the first social media ban, the blackout occurred before SOS Medias started using the site.

“The media climate is just getting worse,” says the SOS reporter, careful to make sure no one else in the restaurant was listening. “I’m not sure if we can keep reporting and posting even a few days from now.”