How can “self-knowledge through numbers” open new spaces for public engagement with health policy, and for the necessary political debate around important issues of personal data and health?

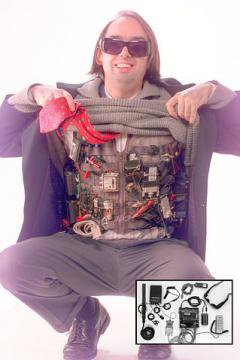

Glogger/Wikimedia Commons. Some rights reserved.Currently there is increasing interest in the phenomenon of self-tracking and quantification, from both the academic research community and from commercial actors. Monitoring fitness, sleep, mood or other kinds of everyday physical activity and logging it with the use of simple spreadsheets and mobile phone applications, or the interfaces provided by commercial or custom-made wearable electronic devices is a trend that is gaining ground in the US and Europe.

Mostly as a means for sports-related physical enhancement, self-tracking is also popular for weight and health management. Although commercial wearable devices such as Jawbone and Fitbit provide some form of social networking function or another, it seems that today individuals who self-track also form their own communities across platforms, and often beyond those prescribed by the devices they use, online and offline.

In what follows, I focus on the political potential of such communities: can they be thought of as new forms of publics? Could they offer opportunities to discuss, deliberate and help organise the future of the welfare state, influence legislation around health and other personal data ownership or legislation regarding privacy?

Quantified Self

One spreading community of “lifelogging” is the Quantified Self. There are numerous online articles about the Quantified Self as a group; the generalised term “quantified self” is also becoming common in the media. Here, however, in using capitals, I am interested in the Quantified Self (QS) - a community of people who incorporate technology such as wearable sensors to log data on various aspects of their everyday lives. They are people who self-monitor (or self-track or lifelog) in between other things, food consumption, mood changes, physical activity. QS now includes 341 meet-ups, 150 groups worldwide, approx. 30,000 members, 115 cities, 37 countries.

A “movement”?

QS has called itself a movement, however there is no statement of the group as such and it should not be confused with a political movement. As a phenomenon born in the San Francisco area, it should perhaps be understood in the context of a larger, ongoing trend of Californian techno-utopianism. This is what Richard Barbrook (referring to WIRED, a leading American technological innovation magazine) described in 1995 as follows: “the social liberalism of New Left and the economic liberalism of New Right have converged into an ambiguous dream of a hi-tech Jeffersonian democracy”. Wired of course is central to how ideas and definitions about the QS have disseminated since 2006. Together with co-editor Kevin Kelly, Gary Wolf co-founder of the Quantified Self, introduced the concept. They did not announce it as a political movement, but as a movement towards self-knowledge and large scale data gathering.

In a recent conversation with Ernesto Ramirez, organiser of the Bay Area meet-ups, he emphasised that QS is not an organisation that is interested in politics and does not make a profit, but is rather a learning community. The group mostly focuses on self-experimentation, but there is encouragement to share this self-knowledge in gatherings such as show-and-tell meet-ups, and annual conferences in the US and Europe.

Fitness buffs or “soft resistance”?

So if QS is not a movement, can it nevertheless be political and enable public engagement? Dawn Nafus & Jamie Sherman from IntelLabs suggest that QS is evidence of what they call “soft resistance” to the hegemony of Big Data - because they are seen as DIY actors who create and hack smaller, fragmented databases. However, nothing stops the industry from using smaller scale databases – in fact wearable sensors, fitness and medical companies mainly harvest these kinds of data. Others take a more dismissive view of the political potential of QS. A loosely organised group, the MIT Review wrote in 2011, QS is:

“part of a rapidly growing movement of fitness buffs, techno-geeks, and patients with chronic conditions who obsessively monitor various personal metrics […] driven by the idea that collecting detailed data can help them make better choices about their health and behavior”.

But the MIT also got it slightly wrong: QS is not just about individual choice and behavioural change. They may have been a techno-geek community in 2008 or 2011, but the progressively lower cost of sensors and the new generation of mobiles (and let's not underestimate the entry of actors such as Google and Apple in the digital health arena) means that things have moved on.

For me, the potential of QS for public participation lies in the show and tell meet-ups that constitute a central feature of this community. Meet-ups enable the exchange of stories about the success or failure of lifelogging practices; they allow people to connect and form synergies around common interests, and to explore wider questions such as personal data management and ownership. QS meet-ups have a diverse constitution; geeks, start-ups, developers, entrepreneurs, visionaries, researchers, patients – everyone has access to a meeting. The talks and demonstrations (show-and-tell) are neither too technical nor too wordy for the uninitiated. But through these sessions, members touch upon key political issues and create temporary spaces of dialogue: what happens to personal data, who has access to these data (is it private individuals, governments or corporations)? For what purposes (medical research)? And how can these data be interpreted (by algorithms, visualisations) and used to tell stories about people?

“This is not about small data or big data, it is about OUR data”

These are important political questions that need to be debated in the public sphere. In the era of Big Data, after the Snowden affair and the Open Data movement, where governments are required to add transparency to their actions by allowing access to a wealth and variety of databases in the US and the EU, questions around data are widely recognised to be a very political issue.

Gary Wolf put this rather succinctly at the San Francisco meet-up in the Exploratorium in March: “This is not about small data or big data, it is about OUR data”. In other words, Wolf suggests that self-tracking and life-logging data may be about us, but they should also be ours to generate, harvest, access, manipulate, interpret, and use - even sell.

Ownership versus open access is of course a big discussion that has been a legal headache for the music industry in the digital age; now it seems discussions about access to and ownership of our most intimate personal data are becoming a similar challenge for governments, companies and researchers alike. Meanwhile, there are developers and individuals who pioneer the setting up or use of platforms for donating genetic data to research repositories, and new pathways to data access and rights.

But what do we do with data?

"We're now capturing more data on what it means to be a human being than at any time in history, and what we're learning isn't just telling us what we are. It's telling us what we can be", says biohacker Dave Asprey – one of the many advocates of extreme regimes of self-monitoring and enhancement that the media have focused on.

The question “what to do with the data” exacts responses from actors with very different stakes in this field. Wolf himself, whose interest is with self-knowledge but on a larger scale, writing about QS in his forthcoming book QS & The Macroscope, invokes the term “macroscope” to refer to a “technological system that radically increases our ability to gather data in nature, and to analyze it for meaning”. Clinical trial Dr. Ravi Bhatia, a professor of haematology and the director of the stem cell and leukemia program at the City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte (Los Angeles County) notes that the detailed personal data collected by a given Quantified Selfer may be of genuine medical utility - but only for that specific individual. I attended a recent discussion about ageing and the Future of Caregiving & Technology at the Institute for the Future, where Rajiv Mehta was keen that health care professionals (HCPs) should be informed by communities of deeply-engaged and knowledgeable patients such as QS (February 26, 2014). Even TV personality Takei wondered recently, in his YouTube podcast, that once we collect this information, all these data, what do we do with it?

Members of the QS community address the challenge in a more informed way. Having had the experience of tracking and self-quantifying for a long time, many of them experimenting with a variety of devices and wearables, they reach a point where they are faced with a huge volume of data and limited means of interpretation. At the same time, they may be unable to harvest “raw” data from their devices (if the device or the application does not allow access). Or, after show and tell meetings, users may want to share personal data and visualisations with other members of the community. Quantified Self Labs works with a community of developers to develop API tools (tools that allow export of data into CSV files) that allow access to such walled gardens, in order to extract data out of devices. Originating from the QS Europe conference in 2013, when a group of developers had a particularly intense conversation about API integration, QS Labs has put together an active Toolmakers list which brings together people involved in building tracking tools and technological devices.

“Smart” and experimental publics?

This combination of experimentation, the show-and-tell mode of operation, and developing tools that respond to the needs of a community and synch with how technologies advance, represents a different mode of public participation and way of producing political voice to those in existing modes of deliberation. The everyday social and material experimentation of QS self-quantifiers with tracking technologies brings them close to the important political issues of data privacy, ownership and sharing – and what is more, it is done in public: in public physical settings, such as meet-ups, or through various social networking sites, or the built-in social platforms of tracing apps.

In this sense, I want to argue that the QS community may be an exemplary community when thinking about publics emerging around “smart” technologies. Such publics are made, constructed, and performed in culture and the media in narratives about smart technologies, and within wider narratives of economic growth, environmental crisis, economic progress and technological innovation. Using digital technologies and media, they potentially engage with common concerns and important political issues beyond the venues of traditional representational politics and bureaucracies.

Clearly, at this point the social and community aspects that are enabled by self-quantifying practices and devices are stronger than its political dimensions. But what are the obstacles that might prevent it growing as a public? And what further support or forms of participation might be needed for this public to develop? Self-experimentation is not sufficient in itself to lead to public engagement with health policy; political questions cannot be addressed with apps and smart phones, and sociopolitical solutions can hardly be provided by Silicon Valley start-ups. As John Dewey argues, a public needs to recognise that their interests are affected in order to express itself as a public. But this is perhaps why the power of QS to participate in political debate around the important issues of personal data and health is strongly linked to how it frames itself in the narratives it generates in the media.

Who decides?

This is not to say that smart technologies and new digital media practices can substitute for ‘real’ politics. But let us think beyond technological objects in a fetishistic way, to a relationship between people and these objects which does not confine them to the role of mere consumers or users. There are other identities people can occupy with and through new technologies - what about citizenship? QS is an early example of how we can and should be members of a public that participates in decision-making about our super “smart” future.

Notes:

The insights in this article come from research undertaken during research secondment (funded by the RCUK Digital Economy NEMODE) at the Research Centre Science and Justice, University of California, Santa Cruz, between January – April 2014.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.