Funded by children's sticky nickels and leftover allowances, comic books were initially started as a way to keep presses running. A man named Will Eisner had the radical idea that these books were as important and as artistic as music, or paintings, or books — and he changed them, made them the place where super men and women, marvels, detectives, and the fantastic live.

Comics' existence — like many of the stories they told — wasn't without threats. Censorship, sexism, and racism have worked like vehement supervillains, determined to derail the strides of progress being made. And each time they've been tested, the books have come back faster, stronger, better than before.

Today, comic books command a seat at pop culture's table. They rule the box office and television screens. But most of all, from Superman to Sex Criminals, they're still places where the greatest stories are being told. Here are 50 comic books that explain the vast history, how certain books shaped the medium, and the state of comics today:

-

Action Comics No. 1 (1938): The first superhero

This is where the superhero begins.

Here's Superman lifting a truck over his head with his bare hands. Imagine being a kid and seeing this concept — and this character — for the first time. It must have been amazing. Action Comics No. 1 is the reason we have Batman, Green Lantern, the Avengers, the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, and every other superhero. It's also the reason that when we dream of being super, we dream of having fantastic powers.

"That was the dawn of superpowers," DC Comics publisher Jim Lee told me. "There were pulp characters before that, but no one could lift a car, be bulletproof, and leap over buildings in a single bound. And I think that was the start of superhero-dom and the idea that people could have crazy strange powers that made them gods among men."

-

Captain America Comics No. 1 (1941): The beginning of Jack Kirby's legend

Jack Kirby is a comic book deity. Born Jacob Kurtzberg in 1917, Kirby grew up in Manhattan's Lower East Side. Art was his way of dreaming up better places (the LES of 1917 was a lot grittier than it is now), and his comics did the same for readers.

In Captain America Comics No. 1, one of his earliest works, you can see the force in the way Kirby draws and adds curve to Cap's legs — this would become a Kirby signature. The faces he drew were expressive, too — you can often tell a Kirby face by the character's mouth and nose. And as Kirby began producing more work, he began showing off an innate talent for putting his limitless imagination (think supervillains in intricate, intergalactic headgear) onto paper.

Kirby brought a crackling, kinetic force to his art, along with a searing thoughtfulness when it came to structure, composition, depth, and perspective. Kirby made comic books, and the people who create them, better.

-

The Dark Knight Returns No. 1 (1986): The antihero becomes a legend

The Dark Knight Returns isn't Batman's first appearance, but it's the most epochal. Today, in large part due to Christopher Nolan's cinematic interpretation of the hero in films like The Dark Knight, Batman is seen as a dark, brooding antihero. Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns was the comic book that crystallized that image back in the '80s. Set in a dystopian future, The Dark Knight Returns imagines a world where Superman is an agent of the government and crime is rampant. The series explores the idea of a hero going as dark as any villain. Fear, it argues, can be as inspiring as hope.

"I don't remember any covers with a zillion characters fighting with flame and smoke," Batman artist Greg Capullo told me. "They're beautiful pieces of art. But they're there, and they're gone. They didn't live with me. The Dark Knight Returns is iconic. It sticks in my head because of its simplicity."

-

Giant Size X-Men No. 1 (1975): The comic that saved the X-Men

When they were first introduced, the X-Men were not very popular. In fact, in 1969 the X-Men were the worst-selling title at the company.

That title was eventually halted, and brought back to life with Giant Size X-Men No. 1 in 1975. The roster was expanded to include characters like Storm, Nightcrawler, Wolverine, and Colossus — heroes with different skin colors, traits, and accents than readers were used to seeing. Writer Len Wein (and eventually Chris Claremont) and artist Dave Cockrum carved out personas, voices, and catchphrases for each of these characters, and their stories became immensely popular. Many of these characters have become among the most well-known and well-loved in comic book history.

-

Fantastic Four No. 1 (1961): How Marvel lost its first family

Marvel's movie rights have become their own story within the comics industry. There's no better example of how the fight over those rights have affected the publishing side of the business than the Fantastic Four.

In 1961, when Marvel was on the precipice of failure, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby created the Fantastic Four — a team of space adventurers who each obtain different powers after a mysterious voyage — to tap into the popularity of the Justice League. The team was massively popular not only because of its adventures, but also because of the book's quieter stories about personality and family dynamics. The book's sales saved Marvel, paving the way for heroes like the Avengers, Spider-Man, and the X-Men.

Yet despite the Fantastic Four's importance to Marvel as a whole, the movie rights of this first family belong to Fox. (Marvel is owned by Disney.) And in recent years, the Four haven't been big players in the Marvel universe, leading to speculation that the company was freezing out the characters to spite Fox. In 2014, Marvel announced it would be canceling the title. A new Fantastic Four movie is due in August 2015 — produced by Fox.

-

Spawn No. 1 (1992): The good guys aren't always good

In the 1980s and early part of the '90s, comic book fans were divided into two camps: DC or Marvel. Superman or Wolverine? Joker or Magneto? Wonder Woman or Storm? These battles would divide friendships and split households.

Then Todd McFarlane's Spawn entered the fray. McFarlane, a former Marvel artist, broke off from the company to create Image. Spawn and Image's other titles had rebellion and mud running in their veins. Spawn was ultra-violent, darker and blunter than the heroes at Marvel and DC were. After all, this was a character who made a deal with Satan and killed child murderers and pedophiles. The first issue sold an astronomic 1.7 million copies, proving there was a thirst for something darker and different than DC and Marvel had tapped.

-

Sensation Comics No. 1 (1941): The first lady of DC Comics is born

Wonder Woman, a.k.a. Diana Prince, made her first cover appearance in Sensation Comics No. 1, published in 1942. Her creator was an eccentric man named William Moulton Marston, a psychologist who invented the polygraph. Marston's vision for Wonder Woman was to present an alternative hero who didn't have to triumph with brute strength and violence.

"It seemed to me, from a psychological angle, that the comics' worst offense was their blood-curdling masculinity," Marston wrote in an essay for The American Scholar. "It's smart to be strong. It's big to be generous, but it's sissified according to exclusively male rules to be tender, loving, affectionate. … Not even girls want to be girls as long as their feminine stereotype lacks force."

Wonder Woman was also an anomaly in that many of Marston's stories had her on Paradise Island, where men were not allowed. This was in contrast to popular romance comics and characters like Betty and Veronica, whose sole purpose was to seemingly fight over a boyfriend.

While Wonder Woman is more of a brawler today, it's important to remember Marston's vision of an unconventional hero who didn't need a man to determine her worth and was free to be herself.

-

Daredevil No. 168 (1981): Frank Miller takes us to the dark side

In the comic book world, Daredevil was always a bit of a designer impostor Spider-Man. No matter who was writing the blind hero with super-senses, Daredevil occupied the same city and same space as the web-slinger did. He even borrowed many of the same tricks. And, well, no one really cared.

Enter the aggressively talented Frank Miller (who would go on to create The Dark Knight Returns). He officially took over the book in 1981 and made his debut with No. 168. Miller had already been creating the art, and he was given a shot after writer Roger McKenzie disagreed with Marvel editor Denny O'Neill on the character's editorial direction.

Miller took Daredevil back to the grit and violence of the pre–Comics Code 1950s, a world most comics had left behind. He made the city of New York fearsome, and he grounded the comic in a dark expressionism that would inspire writers and artists in comics industry for years to come. Miller's influence lives with the character to this day.

-

Strange Tales No. 146 (1966): Steve Ditko's strange legacy

Steve Ditko is best known for, along with Stan Lee, creating Spider-Man. But his work in bringing Dr. Strange to life is just as iconic. While Lee and Jack Kirby created characters who dug deep into the more human side of superheroes, Ditko focused even more intimately on the individual.

In Dr. Strange he was given free rein to explore the character, Dr. Stephen Strange, who was, by all means, kind of a jerk. The world Ditko created for Dr. Strange, was trippy, interdimensional, laced with an acid kick. It was loopy in the way the Winchester mansion and Escher drawings are. Nothing made sense, and everything doubled back on itself.

Ditko left the comic and Marvel after No. 146 (he would return in 1979), but not before creating one last iconic cover for the hero.

-

Amazing Spider-Man No. 40 (1966): Spider-Man becomes a mainstream hero

"Amazing Spider-Man number 40: Spidey Saves the Day — it's the first comic I ever bought," Dan Didio, publisher of DC Comics told me when asked to pick one cover that stuck with him throughout his many years as a fan.

"[It's] John Romita art. And I was a comic book fan ever since," he said. Romita's son now works at DC Comics.

Romita was as crucial to Spider-Man as Spider-Man was to his career. With a background in romance comics, Romita was asked to draw Spider-Man after legendary artist and Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko left the title. Romita's style was starkly different from Ditko's work, which was known for its moodiness and relatively grounded realism.

Romita made Peter Parker look more like Hollywood actor, giving him mainstream appeal. This helped increase the book's sales, Sean Howe, author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, explained. One of Romita's most significant moves was giving life to Mary Jane Watson and adding some glamour to Gwen Stacy — two women who would go on to leave their mark on Spider-Man's legacy.

-

Amazing Spider-Man No. 1 (2014): Peter Parker is eternal

Thanks to Dark Knight director Christopher Nolan, the X-Men franchise, and segments of Iron Man and Captain America, the superhero world often seems to belong to grim, ultra-serious heroes. Marvel's flagship superhero, Spider-Man, doesn't fit into that super-dark role. Perhaps that's one of the reasons Sony's Amazing Spider-Man 2 disappointed.

But in the comics, it's a different story. Marvel "killed" Peter Parker in 2012, swapping his brain with that of the villainous Doctor Octopus (anything can happen in comic books). The result was a bad guy in Spider-Man's body and a darker, more sinister hero called "Superior Spider-Man" — it left fans anxiously waiting for Peter Parker's return.

Marvel resurrected Peter Parker in Amazing Spider-Man No. 1 in 2014. The issue went on to become the top-selling comic of 2014, a testament to the power of Peter Parker and the idea that he will never get old.

-

Ms. Marvel No. 1 (2014): This generation's Peter Parker

When a Marvel character has Marvel in his or her name, it's a massive deal. Thus, it was big news when in 2013 Marvel announced that Kamala Khan, a Muslim, Pakistani-American teenage girl with brown skin, was going to take up the title of Ms. Marvel. There have been Muslim superheroes before, and there have been superheroes who are teenage girls. But there's never been anyone quite like Kamala. She's awkward, hopeful, conflicted, altruistic, and she is redefining what heroism means and what a hero looks like.

Plus Ms. Marvel is one of Marvel's top-selling titles. Kamala is very well a new hero for a different generation of readers, much like Peter Parker was.

-

Amazing Spider-Man No. 121(1973): The Night Gwen Stacy Died

Though Peter Parker and Bruce Wayne had similar tragedies affect their lives, their mentalities are different. Wayne's ideology is rooted in the idea that what happened to him shouldn't happen to anyone else. Parker's is deeply personal. It's something he could have stopped.

Gwen Stacy's death in this issue hit Parker, and readers, like a semi. She died while he was trying to save her, shocking readers who thought deaths were only part of origin stories. People, especially Parker's true love, didn't die under a superhero's watch. Her death plunged Parker into a dark hole of grief, leading him to seek revenge.

The absence of Gwen Stacy changed Spider-Man's trajectory and universe, bringing characters like Mary Jane Watson to the forefront and elevating the Green Goblin to legendary status. It also, according to some critics, set a trend of superhero wives and girlfriends being turned into disposable victims of violence because of their relationships to heroes.

-

Uncanny X-Men No. 211 (1986): The crossover that started it all

The Marvel universe is built on crossovers. It's fun seeing the Avengers, X-Men, and everybody else team up to take on some big bad. But more pertinent to Marvel is that crossovers like Avengers vs. X-Men, Axis, and Civil War make money.

The grandparent to Marvel's crossovers is what's called the Mutant Massacre, an arc by Chris Claremont, Louise "Weezy" Simonson, and Walter Simonson, with pencils by John Romita Jr. and Sal Buscema. Though the murder of mutants called Morlocks is the foundation of the arc, we see appearances from Reed Richards (of Fantastic Four fame), Thor, the X-Men, and Dr. Doom in this story. The story took place over three months, 12 issues, and six different comics.

-

Uncanny X-Men No. 135 (1980): The Phoenix is born

Comics haven't always been kind to women. Women were often used solely as love interests (see: Captain Marvel), or they were victims because they had superhero boyfriends and husbands (see: Gwen Stacy). They were grievously injured (see: Batgirl), or they were characters who used manipulation or subterfuge to get ahead and were summarily punished for it (see: Black Widow).

This loaded history is what makes Chris Claremont's partnership with artist/writer John Byrne so special. The two fleshed out various X-Women, giving them dynamic storylines and upgrading their powers. One of these women was Jean Grey, who became the host to — and was eventually overwhelmed by — one of the most powerful cosmic entities in the Marvel Universe: the Phoenix.

Grey went from meek and mild Marvel Girl to the genocidal Phoenix, in a comic wrapped around the idea of awakenings, identity, and empowerment. The story has gone on to change the future of the comic, and turned Grey into a searing figure who defines the X-Men.

-

Crisis on Infinite Earths No. 7 (1985): The last time superhero deaths mattered

Purists consider this comic to be the last time character deaths mattered. In the Crisis arc, we see the deaths of two beloved heroes: Barry Allen (the Flash) and, in this issue, Supergirl.

"The idea that such a popular and beautiful, all-American character could die off from comic books was ground-shaking," Jono Jarrett, a board member of Geeks OUT, a gay geek organization, told me. "This was before it became a cliché that beloved characters would seemingly perish in spectacular, sales-boosting events that undid themselves in time for the next movie."

The art — Superman clutching a battered Supergirl — by George Perez drives that home. Perez's art is an homage or riff on Uncanny X-Men No. 136 by John Byrne, with Superman, not Cyclops, holding a dead Supergirl rather than Jean Grey.

-

The Killing Joke (1988): God loves, and Batman kills

There might not be a more "WTF" moment in comic books than the end of Alan Moore and Brian Bolland's one-shot comic The Killing Joke. In the comic's final panels, readers see Batman come face to face with a cackling Joker. Up until this final scene, the Joker has terrorized Batman — torturing Commissioner Gordon and shooting and sexually assaulting Gordon's daughter, Barbara. With all that pent-up frustration and anger building, Batman, now laughing as well, takes his nemesis by the throat, just as a car pulls up. Two panels later, the laughing and the comic end, as the headlights go out.

Did Batman go against his own beliefs and kill someone? Did he go insane? Are both characters insane? What is Moore trying to say?

The ending has been debated, tossed, turned, lathered, rinsed, and repeated countless times. Moore has said he believes Batman and Joker are "mirror images of each other," lending even more ambiguity to his story. Therein lies the lasting power of Moore's book — the ending is aggressively ambiguous, forcing readers to decide how it ends, and Moore understands that there's beauty in putting absolute control in readers' hands and then forcing them to make a decision.

-

Superman No. 75 (1992): Even Superman can die

The most business the comics industry ever did on one day was on November 18, 1992 — the day DC published The Death of Superman.

An estimated $30 million of business was done that day. The story was nothing to write home about — Superman fights an unstoppable villain named Doomsday and seemingly dies (he was brought back less than a year later) — but the event reflected the growing intersection of pop culture and comic books. In a more cynical view, The Death of Superman's sales and marketing opportunities are also the reason many believe that, story-wise, character deaths are more about a company wanting to make money than about delivering a fantastic story.

-

Uncanny X-Men No. 141 (1981): Days of Future Past

This cover by artist John Byrne, with Wolverine and a brunette woman spotlit and standing in front of a checklist of slain and fallen X-Men, imprinted itself upon fans' brains. Just seeing it makes many comic book readers' hands tremble in anticipation. It's jarring and disorienting, an image artists have paid homage to over and over. The story, by the well-known Chris Claremont and Byrne, is one of the most influential tales ever written, primarily for its lack of justice and goodness.

Claremont and Byrne imagined a futuristic, bleak world where mutants were hunted down amid a landscape of grim grays and broken rubble. To "fix" this, the remaining X-Men bend time and send Kitty Pryde back, while Claremont and Byrne weave a tale that's purposely confusing. The tale's open ending ("Does that mean we changed the future?" Angel asks in the next issue) provides no clue, compass, or hope to readers.

-

Life With Archie No. 36 (2014): How will we remember Archie?

Archie, like a lot of comic book characters, met his own death in 2014 in Life With Archie No. 36. It was strange, in that the tone of the comic book felt grounded in real-life conversations and topics — Archie was shot and killed at a restaurant while trying to defend his gay friend Kevin Keller — but Archie comics are better known for telling escapist, nostalgic feel-good stories, rather than trying to reflect real life back at the reader.

Here Archie was, making a statement on gun violence and gay rights. To some fans, the death reeked of a publicity stunt. After all, Archie lived on in other titles.

But the event does bring up a more valid point about Archie and his place in comics. For years, Archie banked on nostalgia, while newer, innovative, and darker comics became the hot titles. So how can a title like Archie stay relevant? Introducing stories about current events readers are dealing with in their own lives is a tried-and-true tactic.

Perhaps Archie's death, no matter how inelegant, is a way of bringing the Riverdale gang back to relevancy. Two months after Archie's death, Fox announced it would be producing a show based on the comics.

-

Crime Suspenstories No. 16 (1953): A story behind the cover

We're often told not to judge books by their covers. Yet if you think about it, judging a book by its cover is exactly what comic books ask you to do. They want to hook you with that searing cover image. And in order to do that, you need colors that not only make sense with the story but also pop.

Hooking people in was Marie Severin's job. Severin was a colorist at EC Comics, and was tasked with, according to Severin herself, "upgrading the look of the books. He [editor Harvey Kurtzman] wanted them to look more like Prince Valiant in the newspaper."

Severin brought EC's covers and art to vibrant life. She was great for business, vaulting EC to success. Though readers loved her smoldering colors, Severin seemed to always direct credit to the writers and artists.

Severin would eventually showcase her skills as an artist and also work at Marvel, where she got the praise from likes of legends such as Jack Kirby. Severin was the first woman inducted into the Eisner Comics Hall of Fame in 2001.

-

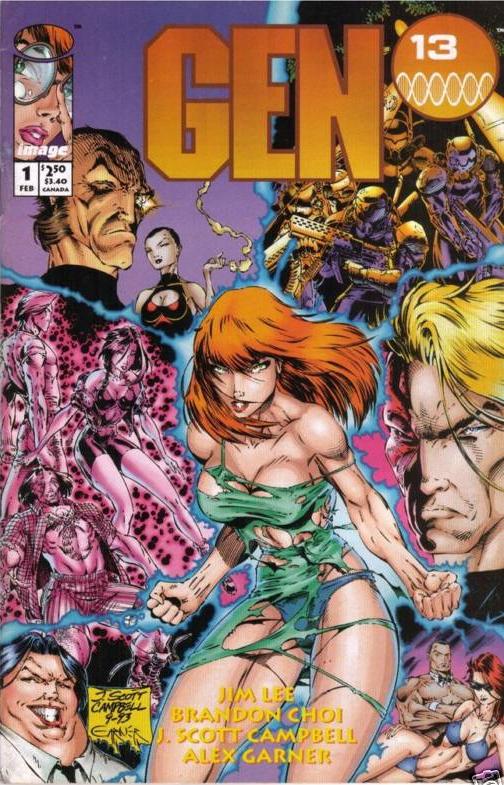

Gen13 No. 1 (1994): How women became super sex objects

Gen13 is a relic of an industry mired in a pattern of creating female characters who existed only to be objectified. The story, created in 1994 at Image Comics and eventually sold to DC, revolved around a young woman named Caitlin Fairchild who had super-strength.

The comic was compelling, riffing on ideas from X-Men, as we followed around "gen-active" teens with superpowers. But the female characters were often shown with their clothes ripping strategically, being subdued, or contorting themselves into seductive "fighting" poses. Yet Gen13 was also pretty successful in the '90s — perhaps because of this overtly sexualized material.

-

Captain Marvel No. 1 (2012): Carol Danvers goes higher, faster, farther

Many characters in the Marvel Universe have been named Captain Marvel. In 2012, Carol Danvers, the former Ms. Marvel, assumed the title under writer Kelly Sue DeConnick and artist Dexter Soy. DeConnick and Soy fleshed out the character's past experience as an officer in the Air Force and space explorer.

In doing so, they gave Marvel Comics a flawed, imperfect, admirable, forthrightly feminist hero, who became a beacon of inspiration for female readers. Danvers's readers and admirers came to call themselves the Carol Corps., and became a vocal feminist movement in the comics community. Danvers's rich story and her fans' devotion came to fruition in 2014, when Marvel announced that Danvers will get her own movie in 2018. -

Astonishing X-Men No. 51 (2012): The gay wedding of a lifetime

Since their inception, the X-Men have been progressive avatars for minorities and the struggles they face. The X-World has seen horrors like the Legacy Virus (a parallel to AIDS) and the Purifiers (a group of mutant-hating religious zealots), as well as small triumphs like mutant acceptance. In 2012, Marvel celebrated the Supreme Court's decision to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act by having hero Northstar marry his boyfriend, Kyle Jinadu, in Astonishing X-Men No. 51. The cover doesn't hide that fact, either, forthrightly depicting the wedding.

-

Miles Morales: The Ultimate Spider-Man No. 6 (2014): A hero who looks like America

The creation of Miles Morales was both a sad triumph and a barometer of how far comics have to go. Superhero comic books represent the best of humankind, but they had never represented all of humankind. Most heroes were, like their creators, straight white men.

In 2011, the world met a Spider-Man named Miles Morales. Morales, a teen who is black and Hispanic, lives in Marvel's Ultimate universe — a parallel universe that has similar heroes to Marvel's regular world but very different storylines. Plenty of fans welcomed the announcement, but there were readers who cried foul that a beloved character like Spider-Man could be black.

Marvel stuck to its guns, and Miles paved the way for characters like the Muslim, Pakistani-American Kamala Khan and the gay X-Man Benjamin Deeds. And if Marvel's 2015 Secret Wars event does combine elements of the Ultimate universe with Marvel's normal universe, as rumored, it isn't too far out there to think Morales will be a big part of the story.

-

Spider-Woman No. 1 variant (2014): Proof that we still have a long way to go

The way women are depicted in comic books has evolved in recent years, but it doesn't mean the industry has done away with the sexism and overt sexualization of female characters than ran rampant in the 1980s and '90s. As a case in point consider Milo Manara's 2014 variant cover for Spider-Woman's solo book.

Known for his erotic comics, Manara bent Spider-Woman, a.k.a. Jessica Drew, into a knees-down, butt-up pose, similar to ones women in his comics are often seen in. It wasn't a good look for Marvel, which has been positioning itself as a publisher that celebrates female and minority empowerment in recent years.

This is not to say that Manara's erotic work shouldn't exist. But the cover raised valid questions as to why Marvel thought it was a good idea to commission a cover from Manara in a book that's supposed to solidify Drew's place as a legitimate hero.

Marvel's editor-in-chief apologized for the cover in August 2014.

-

Storm No. 7 (2015): A superhero trapped in a world that doesn't trust her

In 2014, Storm (Ororo Munroe) was given her own comic book, written by Greg Pak. Pak has an innate, thoughtful sense of the character, but he is equally graceful in crafting a storyline that resonates with the shootings of Mike Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Tamir Rice in Cleveland, Ohio. In the book, Storm is held unlawfully for allegedly trying to crash a plane — it was her word versus a white senator's — and her supporters, most of whom are nonwhite, are nonviolently protesting. Storm breaks free from the building and runs into the crowd, as police wonder whether to shoot.

Al Barrionuevo and Stephanie Hans's (cover) art is intense and arresting — almost surreal. And Pak conveys the tragedy of real-life events and the idea of prejudice in an elevated, respectful way. That they're working with one of the most game-changing characters the comics industry has ever seen, in terms of race, gender, and sexuality, makes it even more effective.

-

Red Sonja No. 7 (2014): Pleasant-smelling women rarely make history

What does progress for women in comic books look like? Maybe it looks like a beautiful, angry warrior named Sonja, who smells so bad that it actively impedes her attempts to get laid. That's the wickedly funny premise of Gail Simone's Red Sonja.

As silly as that might sound, having a stinky, randy warrior woman express sexual frustration is something worth celebrating. Comics have a long history of portraying women solely as sexual objects. But there's been a dearth of comic book women who are in charge of their own sexuality and are drawn that way.

Simone is a veteran of comic books, known for her dazzling run on Birds of Prey as well as for calling out the "women in refrigerators" trope. She's seen a lot of clumsy sexism, railed against it, and inspired other female writers and artists. Her Red Sonja reveals how when women write women in comics, they come up with the sorts of stories men would rarely know how to tell, or even want to tell. And that diversity of perspective is valuable to anyone who loves great storytelling.

-

Bitch Planet No. 2: A love letter for noncompliant women

Kelly Sue DeConnick is a brilliant writer. But her work on Captain Marvel is often accused of pushing an agenda. It's not unlike the way race is brought up with nonwhite writers or queer theory with gay writers. Never mind the many straight white men who write straight white characters but are never accused of having an agenda.

"There’s a certain part of me that’s just like, 'If I’m going to take the heat for it, well … let’s do it then. Let’s steer into the curve,'" DeConnick told the Los Angeles Times in 2014.

That curve is Bitch Planet. It's a classy kiss-off to her critics. DeConnick's "agenda" is out in the open here. It imagines a patriarchal society gone wild. "Noncompliant" women who don't fit society's standards on body type, sexuality, or behavior are sent to a jail in space. On any scale, the comic is as fantastic as it is funny.

"Bitch Planet is as much Val's baby as it is mine," DeConnick told me, referring to her artist Valentine De Landro.

"There's a double-page spread in issue two. And one of the characters — I kept staring at her body type. It's something I don't see in comics," she added. "When we have a scene of them and they're all nude and it's nothing salacious or provocative about it. They're just so human. He just gets across the vulnerability."

-

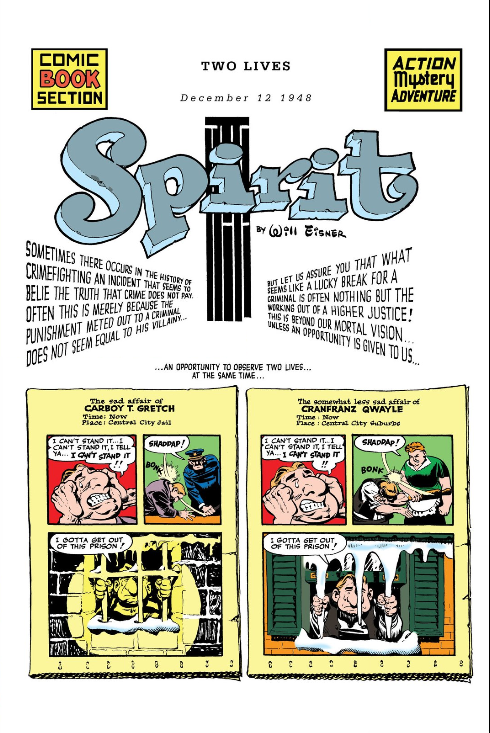

The Spirit No. 446 (1948): How Will Eisner turned comics into an art

Will Eisner's The Spirit isn't technically a comic. It began as a newspaper supplement, a way for broadsheets to get in on the comic book explosion. But if there's anyone worth breaking the rules of this article for, it's Eisner — the grandfather of comic books.

Born in Brooklyn in 1917, Eisner had a vision that comic books could be better. When he began his career, comic books were largely collections of newspaper comic strips and mostly an excuse to keep the printers warm on weekends. Eisner approached comic books as a literary art form meant to be taken seriously.

Eisner wanted to tell great stories and treat his craft with the care it deserved. He truly believed everyone of all ages could appreciate a good story. Eisner's credo is evident in The Spirit, a crime-fighting story absent superhumans, superpowers, or costumes (save for a small mask).

In the story pictured here, "Two Lives," Eisner explores the lives of Carboy Gretch and Cranfranz Qwayle, two men who long for different lives. Gretch wants out of prison, and Qwayle wants out of his marriage. This is not so much a story about crime as it is a reflection of being trapped in a life you can't escape. Eisner continually experimented with form and themes, ultimately making The Spirit one of the most important titles in comic book history and laying the groundwork for all the writers and artists who came after him.

-

Crime and Suspenstories No. 22 (1954): The story that killed comics' Golden Age

Why do superheroes so dominate the comic book world? The answer dates back to 1954, when a Senate hearing was called to discuss the content of comics. At the time, artists and writers were playing with elements like gore and terror, and there was a much-believed (and unfounded) idea that comic books led people down paths of violence and depravity.

The focus of the hearing was on a company called EC Comics, and in particular issue No. 22 of Crime Suspenstories.

"Here is your May 22 issue. This seems to be a man with a bloody ax holding a woman's head up, which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?" Senator Carey Estes Kefauver asked EC Comics editor William Gaines.

From then on, comics suffered from bad press. Horror comics all but disappeared. The industry self-censored its art by creating a Comics Code, and publishers began pumping all of their resources into superheroes and neglecting other forms of comics. The code and its repercussions stunted the creativity of the comic book industry, something the industry is finally working through.

-

Avengers No. 54 (1968): The birth of a new kind of evil

For a long time in comic books, evil was depicted in a superficial, almost cheesy way. Silly villains with silly powers primarily wanted to rob banks. A lot of this was due to the damaging mandate called the Comics Code, which forced publishers to sanitize their books. According to the Comics Code, publishers couldn't have fearsome creatures like vampires or werewolves, cops were always to be trusted, and evil could never win.

The Code forced writers to figure out ways to smuggle in bigger, bulkier themes, to find ways to make them fit the parameters. Or, as writer Roy Thomas did with his introduction of Ultron, some writers found ways to subvert and chip away at the rules.

In this arc, Thomas has Ultron assemble a group of silly villains who call themselves the "Masters of Evil." Their plan is to capture the Avengers and blow them up in a hydrogen bomb over the city of Manhattan. In a world where a villain's chief goal might have been to rob a bank or best a hero in a fight, this kind of evil was unimaginable.

Eventually the Avengers prevail, but not before Thomas symbolically casts these sillier villains aside, making way for a more serious, more vindictive, more insidious threat — the kind of villain we still read about today.

-

The Sandman No. 1 (1989): Neil Gaiman tells us to follow our dreams

Neil Gaiman's Sandman is a book spoken of in the same way some people talk about peak athletes like Michael Jordan or Roger Federer. The book, published by DC's Vertigo imprint in 1988, revitalized the Jack Kirby/Ernie Chua/Joe Simon/Michael Fleisher book from 1974.

The story stars Dream, a.k.a. Morpheus, a.k.a. the Lord of Dreams, in a saga that begins amid the darkness of horror and ascends into surreal, sublime fantasy. But it lacks a traditional superhero. That it did so well against the likes of Superman and Batman is a testament to the idea that comic book readers will gravitate toward great stories.

The Sandman paved the way for more fantastic titles at Vertigo and was one of the most influential in terms of shaping what the modern age of comics would look like.

-

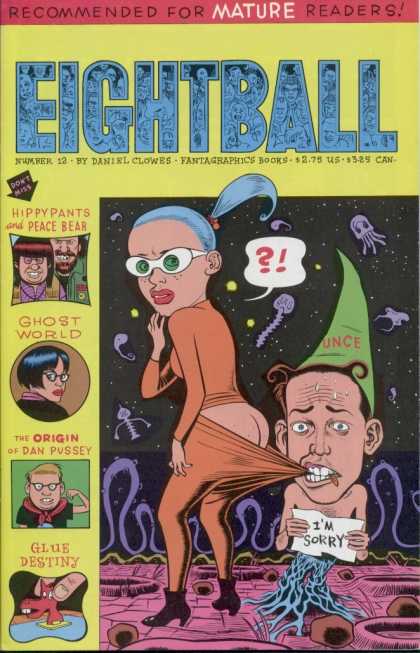

Eightball No. 12 (1993): The alternative answer

Daniel Clowes is one of the most influential cartoonists in history. His works have inspired a generation of artists, writers, and even Shia LaBeouf, who plagiarized one of his comics. Clowes is better-known to mainstream folks as the man who wrote the 2001 film Ghost World, but that story, as well as Art School Confidential, both lived on in his 1989 comic book Eightball.

Eightball was screwy, irreverent, and influenced by punk rock. The art was beguiling, looking childish and dreamy at times, but it carried mature messages and cultural critiques. The characters Clowes built, like Enid Coleslaw (the protagonist of Ghost World), paved the way for many characters to come.

Clowes wanted to create comics that spoke to adults and characters readers would not necessarily aspire to be. He wanted to show genuine, fallible, faulty human beings. In doing so, he opened up a different world and a new kind of comic book to his readers.

-

Love & Rockets No. 31 (1989): Three brothers gave us a whole new world we never wanted to leave

It's hard to pick just one issue of Love and Rockets to feature without feeling like you're not giving the brothers Hernandez — Gilbert, Jaime, Mario — enough credit. That's because one issue can't capture the vast and extensive worlds and characters these brothers created.

Love & Rockets doesn't read like a conventional comic. There are no punchlines or smirky panels. The action is subtle. And the art is efficient — there aren't whirlpools of ink swirling in Jaime's panels. This is what makes it so great.

The stories follow two main throughlines: one about a village in Mexico, another about the punk scene in California as seen through the eyes of Mexican-American characters. The storytelling is rich, imbued with elements of magic, sci-fi, and sexuality. Instead of a story about heroes confined to an ordinary world, L&R showed us ordinary people living in a supernatural world.

-

Watchmen No. 1 (1986): Alan Moore drives us into the darkness

Comics can do some things no other medium can. And the comic book that might best sum this up is Alan Moore's Watchmen. The way you absorb a comic book — your reading pace, how you take in the art, the tone in which you hear a specific line, etc. — is unique to you. And there are certain elements of a comic book, like Dave Gibbons's brilliant art in Watchmen, that will never translate to film. As such, it's not a surprise the Watchmen movie bombed.

But a bad movie can't ruin a comic book as hefty as Watchmen. On one level, this is an intelligent musing on the components of heroism and our cultural obsession with superheroes; on another it captures the suspense of murder and crime, all wrapped up in dense political allegory. At its heart, The Watchmen is Moore's mature and perhaps mortal realization that comic book readers are no longer teenage boys growing up during the Cold War. Readers deserved something different — and thankfully, he gave us just that.

-

Animal Man No. 24 (1990): A comic, and creator, that was all about breaking the rules

Breaking the fourth wall is one of the hardest feats in comic books. It's a gigantic gamble in terms of form and structure. And either you do it really, really well or you fall flat on your face.

Grant Morrison's Animal Man No. 24 is done right, largely because of the meta-story Morrison wants to tell. In it, Morrison provides a blistering critique of the comics industry and its obsession with Watchmen-inspired, "realist" characters through the villain Overman.

Overman is intent on telling the other heroes and Animal Man that he isn't like them. That he's a "real" character, and deserves better, and is somehow more credible than other comic book heroes. And that ultimately becomes his undoing, as he's trapped into a panel that just vanishes.

"We are the creations of sick minds," a shadow in one of the panels says. "The creators … they're not real either."

-

Bone No. 1 (1991): The comic that pushed back against publishers

Jeff Smith created Bone at a time (1991) when creator-owned books barely existed. The interest in comic books was high, but people were mostly interested in titles from corporate juggernauts like Marvel and DC. Readers were drunk on the adventures of the X-Men, Spider-Man, and Superman.

Enter Smith, who created the cute, goofy and aggressively silly Bone cousins and trapped them in a grim world full of death. Bone is as ambitious and cataclysmic as it is funny. What started as a bimonthly comic book ended up becoming a staggering 1,300-plus page, 55-issue, 13-year fantasy saga.

Smith not only gave readers a book that could fill them with childlike wonderment one minute and adult despair the next, but he also helped change the way we — comic book writers and artists included — think about the publishing machine and the stories comic books could tell. Bone, along with other self-published books like Dave Sim's Cerebus, helped shape the terrain of alternative comic books — many of which serve as inspirations for creators today.

-

Chew No. 1 (2009): This is what a renaissance looks like

Chew, along with The Walking Dead, put the publisher Image back on the map. Before the two titles arrived, Image was trapped in an identity crisis. Offering more blatant sex and violence than Marvel and DC wasn't working for the company.

So it began venturing out, taking chances on braver ideas. Chew is a story about a cibopath (a man who can receives psychic visions from whatever he eats, except beets) named Tony (wait for it) Chu, who lives in a world where chicken is banned. Chu solves mysteries by biting things and people. The book showed Image's potential, and it paved the way for the company's current incredible stable of odd and fresh books boasting considerable critical acclaim, like Sex Criminals, East of West, and The Wicked + The Divine.

-

Saga No. 12 (2013): The space opera that became the standard

When Brian K. Vaughn and Fiona Staples's Saga hit shelves in 2012, it elevated the genre. The space opera was sexy and inviting one minute, gorgeously elegiac the next. In its next 11 issues, through decapitations, interspecies love, robot sex, rodent medicals, breastfeeding, and intergalactic ogre genitalia, Saga made clear that this was a book made by and for adults.

And then issue 12 came along, and it was announced that it wasn't going to be sold on Apple devices, because someone thought the issue's depiction of gay sex was somehow too explicit.

That decision was hypocritical, considering how much violence, sex, and nudity had happened in Saga's run until then and how little anyone cared about it. Vaughn, Staples, and Image publisher Eric Stephenson didn't apologize.

"I hope everyone will be able to find an issue that Fiona and I are particularly proud of," Vaughn said. "Fiona and I could always edit the images in question, but everything we put into the book is there to advance our story, not [just] to shock or titillate, so we’re not changing shit."

Their decision wasn't just about sexual equality; it was a brave statement for their art and a promise that they wouldn't back down. That refusal to compromise is part of what makes Saga so great.

-

Sex Criminals No. 5 (2014): Sex sells

Trying to pick one comic book to represent Image Comics' fantastic rise to its current greatness is impossible. You could go with the epic tale that Brian K. Vaughn and Fiona Staples have woven in Saga, or the hip and balletic style in Kieron Gillen and Jamie McKelvie's The Wicked + The Divine. But my pick is Matt Fraction and Chip Zdarsky's Sex Criminals.

Sex Criminals is beautiful, stylish, and hilarious. It's about two people — Suzie and Jon — who can freeze time when they orgasm. Suzie is as thoughtful as Jon is crude (he likes the phrase "cumworld"), and you see their odd, time-freezing relationship through their eyes.

"I think the thing Image wants to be known for is doing things that are new or different," Image publisher Eric Stephenson told me. "The only thing connecting the books we publish is that they’re unique, and I think I’d rather Image’s legacy be that our creators were brave enough to follow their own path rather than simply do the same thing as everyone else."

-

Inhumans No. 12 variant (2015): Phil Noto's art is its own story

One of the most exciting artists working today is Phil Noto, who boasts a ghostly, gauzy, retro style. He's worked for Marvel and DC and is currently bringing Marvel's Black Widow solo series to life.

At New York Comic-Con last year, Marvel announced it had commissioned Noto to create variant covers for several of its titles, and there's probably no better showcase for his artwork than his work for Inhumans, depicting the hero Medusa. It takes your breath away.

Noto's art imagines superheroes in a way that isn't super. There are no bone-crunching fights or giant bubble lettering — the kind of stuff that dominated '60s comic books. Noto's art reimagines heroes as something more understated and less flashy, but his drawings are just as effective and equally stunning. The superhero has taken over pop culture to such a degree that there's increasing room for other interpretations, like Noto's demystification.

-

Multiversity: The Just (2014): An eight-year project that came to life in 2014

Grant Morrison is the mad scientist of comics. He's written about how comic books and superheroes are his religion and inspiration. He's discussed how comic books can elevate the human soul. Those elements are alive in his Multiversity miniseries, which might be the most ambitious project of a hugely expansive career. The comic reportedly took Morrison eight years from conception to execution.

A series of one-shots, Multiversity is a crazy story about an apocalyptic event that threatens all worlds in the DC universe. Worlds bend and fold into one another, and they're all connected by comic books. One world's fiction is another's reality. There are riffs on Marvel, on the golden age of comic books, and even a Watchmen satire. It's so spectacularly wacky that Morrison might be the only person who knows what's truly going on — but it's still fun to hang on for the ride.

-

The Walking Dead No. 100 (2012): The comic that will scar and amaze you

Robert Kirkman's The Walking Dead might be the most successful comic book of the last 10 years, but because it doesn't have a giant movie attached to its name, it's not mentioned in same breath as The Avengers or Superman. It often seems to be trapped in the shadow of its just-got-good television show.

But The Walking Dead comic has been a fantastic, macabre ride. It's richer, more complex, and more brutal than anything the show has offered. It's been a pioneer in elevating the level of gore in the horror genre in comic books.

Issue No. 100 scars you, shakes you up, and asserts that nothing is safe. It guarantees you never will think of the name "Lucille" the same way again.

-

Batman No. 35 "Endgame Pt. 1" (2014): How Batman continues to be a success

For the past few years, Batman enjoyed the kind of success the X-Men did in the 1990s. Month after month, Batman is the top-selling comic, save for special events like character deaths or debuts.

Writer Scott Snyder and artist Greg Capullo's sustained excellence is the motor behind that success. They both have a deep understanding of the character's history — and of where they want to take him next. In Endgame, the two play with a classic idea that makes Batman so popular — he acts as the counterbalance to the rest of the Justice League. But it's also about Batman's relationship to the Joker. The Justice League fighting against Batman is the Joker's evil doing.

"Scott and I both love to death what we're doing on Batman. We have the same love affair with Batman as they [the fans] have," Capullo explained to me about the pressure of working on such a premier title. "You can't control what fans are going to like. What you can do is pour every ounce of yourself into it."

-

Rocket Raccoon No. 1 (2014): Marvel movies can make heroes, too

No comic better speaks to how Marvel's cinematic universe changed the industry than Rocket Raccoon. Before the movie arrived in 2014, the Guardians of the Galaxy comic book had been canceled. Interest was in a death spiral. Then something funny happened.

Marvel announced it was turning the comic into a movie. It rebooted the series, and sales, perhaps unsurprisingly, went through the roof. The popularity of both the comic book and the movie dismantled the existing logic at the time. Before Guardians, it was conventional wisdom that a comic book needed to achieve pop culture relevance (not unlike Batman or Spider-Man) before a movie could be made. Guardians showed the reverse was true: a movie could make a comic book.

Something similar happened to Rocket Raccoon. Debuting after the movie was released, it saw a jaw-dropping 300,000 preorders (100,000 came from a single retailer). Rocket No. 1 finished as the third best-selling comic of 2014, and an example of how Marvel's movie-making and publishing sides can complement each other.

-

The Lumberjanes No. 1 (2014): Proof that there's place for silliness in comic books and in our hearts

There is no more enjoyable comic in existence right now than Lumberjanes. It's part Daria, a twist of Buffy, and a swirl of what teen dreams are made of.

The title tells the story of five badass girls who battle wolves, yetis, gigantic falcons and solve mysteries. It's deeply funny, a breath of fresh air when you get tired of the bone-crunching fights at DC and Marvel. And the Lumberjanes are the perfect counter to anyone tells you serious comics are the only ones that matter.

-

Avengers No. 24 (2013): A 52-year-old saga continues

The most impressive thing about Marvel and DC is that the two companies have continuously maintained some of the longest-running narratives in human history. Each company has handled that burden differently. DC hasn't been afraid of pulling the trigger on reboots and events (its latest, Convergence, is planned for this year), while Marvel has done the opposite. It's leaned into and built on top of its verdant history.

That tradition lives on with Jonathan Hickman's Avengers. Hickman has taken the Avengers to space in the Infinity arc, introduced great, sometimes far out, new characters, and played a game of chess with wave after wave of heroes in Âxis, and is, no doubt, building a house of cards for Marvel's upcoming Secret Wars arc. Hickman's work is intimidating, enveloping, and exponentially richer than anything the movies could give us.

-

Justice League No. 1 (2011): No superhero is safe from a reboot

While Marvel continues to build out its universe and embrace its zany past, DC has had a different approach. In 2011, the company rebooted and relaunched its titles, calling the event the New 52 (52 new series would debut). The thought was that it would make the company's mythology more accessible by trimming the fat while keeping the major storylines that shaped the DC Universe intact.

The first comic to come out of the reboot was Justice League, with writer Geoff Johns and the legendary Jim Lee at the helm. Lee's art is beautiful, and there's something special about seeing characters start over in their relationships. There are some who believe the comic was a letdown, but any comic — no matter how splendid — touted as DC Comics' new beginning would buckle under the years of lore the company built. In 2015, DC announced yet another reboot.

-

Adventure Time No. 5 (2012): You don't need to be serious to be good

There was a time when it was a burn to say comics were for kids. Adventure Time is changing that. The comic is a simple example of how TV cartoons can translate into a new medium, and how comics are a medium, not a genre just made for superhero stories. This issue is about cupcakes, mice kings, rhyming, and a dude named Adventure Tim — though that isn't exactly clear from the cover.

Granted, the source material here is prime stuff, but Adventure Time is showing just how well comics can interpret different kinds of art — and also that kid stuff isn't necessarily a bad thing.

The Superhero

No one is safe: the deaths that shaped comic books

Diversity

The stories that changed the game

The stories being told today

Credits

- Editor Todd VanDerWerff

- Developer Yuri Victor

- Designer Tyson Whiting

- Copy Editor Tanya Pai

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/46020518/50Comics.0.0.jpg)