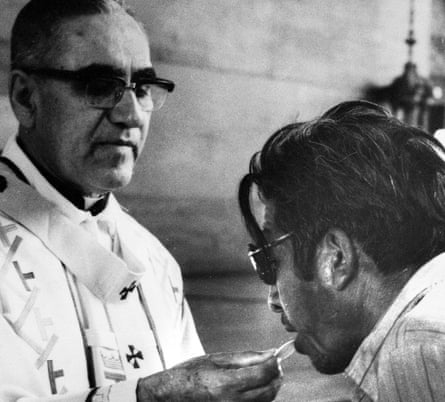

Thirty-five years after he was murdered at the altar, Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero will be beatified in El Salvador on Saturday in a ceremony that aims to at least temporarily unite a conflict-plagued nation.

An envoy of Pope Francis will lead the event, which is expected to draw hundreds of thousands of Catholics to the main square of San Salvador in recognition of a man who was known during the military dictatorship and civil war as a “voice for the voiceless”.

Romero was a deeply divisive figure in life, and his beatification – a step towards his becoming El Salvador’s first saint – was long resisted by rightwing clerics and politicians.

Romero – a conservative who later came to sympathise with the leftwing Liberation Theology movement – was shot through the heart by a sniper during mass at a hospital chapel on 24 March 1980, a day after he admonished the military and called on soldiers to cease killing innocent civilians in the country’s dirty war.

“In the name of God and this suffering population, whose cries reach to the heavens more tumultuous each day, I beg you, I beseech you, I order you, in the name of God, cease the repression,” he said in his final sermon.

At his funeral, the army opened fired on the more than 100,000 mourners, killing dozens.

According to a UN truth commission report in 1993, the officer responsible for ordering the assassination was Roberto d’Aubuisson, who commanded death squads and went on to form the rightwing Arena party.

Like many in El Salvador, the colonel’s family remain divided about the killing and the repercussions. A son, Roberto d’Aubuisson Arrieta, the mayor of the city of Santa Tecla, said the beatification was “good news,” but he continues to dismiss as a “myth” the claim that his father was responsible for the murder that made Romero a martyr.

His aunt Marisa Martinez, however, has a very different view of her brother – and the man he is said to have killed. She is now one of the leaders of the Monseñor Romero Foundation, which promotes the thought and legacy of the defender of the poor.

“When I heard that Monseñor had been assassinated, I knew Roberto must have had something to do with it because of his connections to those [death squad] structures,” she said. “My brother Roberto talked about Monseñor Romero with lots of hatred and anger.”

To the fury of the conservative members of her family, she joined a campaign to have her brother’s name removed from a major Salvadoran thoroughfare. The road, and an international airport, have been named after Romero.

Although many on the right are unhappy about such actions, the momentum behind the drive to make Romero a saint appear unstoppable.

It was a different story in 1990, when the petition was first made by his colleague Rafael Urrutia. The application languished for decades on Vatican shelves.

But in 2012 Pope Benedict XVI – who had previously spearheaded a campaign against Liberation Theology – surprised many by pushing Romero’s case to the Vatican’s office for making saints. Last year, Pope Francis – who has echoed many Liberation Theology tenets in his advocacy for the poor – began the formal beatification process. A Latin American saint reinforces the Argentinian pope’s efforts to restore the church’s influence in the region.

Since the Vatican’s move, even many of Romero’s fiercest former critics have shifted their public opposition and instead tried to re-interpret the message of the martyr. Salvadoran Archbishop José Luis Escobar Alas has organised a campaign called Romero, Martyr of Love, which some believe is an attempt to move the debate about his legacy away from poverty and social justice.

Romero’s younger brother said: “To his last day, my brother believed in God and in God’s calling us to unite in love for the poor, the marginalised and the forgotten.”

History, for the moment at least, appears to be on Romero’s side, but his country has still not found the peace with social justice that he called for.

The civil war ended more than 20 years ago, but El Salvador is trapped in a new kind of civil war, this time fed by political corruption, gang warfare and the US-backed war on drugs. The country now has one of the highest murder rates in the world.

Members of the 18th Street and Mara Salvatrucha gangs – both of which originally grew up among civil war refugees in Los Angeles – are, along with the security forces, responsible for the lion’s share of the killings.

But even the gang members bow their heads to the dead archbishop. “He was criminalised, he was persecuted and he was exterminated by the government, like we are now,” said one gang member.

Romero’s tomb in San Salvador cathedral is now a site of pilgrimage for Catholics across South America, where many already called him a saint.

Political leaders say his message will resonate more loudly after Saturday’s ceremony, which will be attended by six cardinals and more than 100 bishops.

“What does the beatification mean for El Salvador and the world? It means that truth and social justice are now factors that will be present in the life of El Salvador,” said the president, Salvador Sánchez Cerén. Sánchez Cerén is from the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front, which was formed by leftwing rebels the year Romero was killed.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion