/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/34738317/167756157.0.jpg)

A major for-profit college chain is poised to sell off or close all of its 107 campuses, a move that would affect more than 70,000 students.

Corinthian Colleges, Inc., would be the first publicly traded for-profit college company to effectively go out of business in more than a decade — and the largest ever, by a factor of seven.

New regulations for for-profit colleges have been contentious. A judge threw out the Education Department's first attempt, and the department is now trying again, drafting a new regulation to hold programs of study accountable for students' debt and earnings.

But in Corinthian's case, it turns out that existing rules were all the Education Department needed to drive a for-profit to the brink of bankruptcy.

Corinthian students have high tuition and high debt

Headquartered in California, Corinthian operates more than 100 for-profit colleges under three brands: Heald College, Everest (which includes Everest College, Everest University and Everest Institutes), and WyoTech.

The company argues that it enrolls students who aren't certain to succeed and graduates them at a higher rate than community colleges. But that comes at a much, much higher cost with lackluster results in the job market.

If you're arguing against for-profit colleges, there's a good chance Corinthian is your go-to example. According to a 2010 analysis from BMO Capital Markets and Education Department data:

- About half of its students drop out.

- Graduates' annual average earnings hovered around $21,000 in 2012.

- Just one-fifth of students were paying down the principal on their student loan, and on average, student debt repayment took up more than one-third of their discretionary income.

- Within three years, one in five students defaulted on their student loans.

- Tuition is high — for a certificate in its medical assistant program, almost $20,000 per year, for one example.

Corinthian stands out among for-profits for how bad it looks in the statistics.

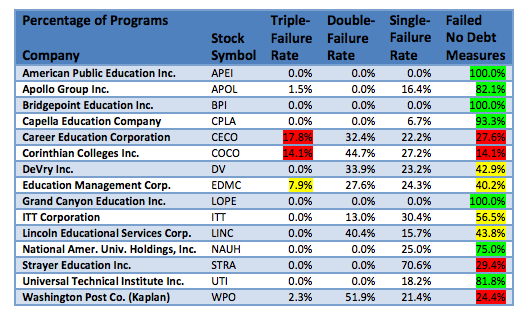

Under proposed federal regulations that never took effect, colleges' programs of study would have had to pass at least one of three tests to participate in financial aid programs. Students' debts should amount to no more more than 12 percent of their earnings or 30 percent of their discretionary earnings, and at least 35 percent of their students' federal loans should be being repaid. (The tests would have been applied to programs, not colleges, so Everest College's medical assistant program would have had to pass separately from its dental assistant program, and so on.)

Most of Corinthian's programs passed at least one test — enough to satisfy the federal government. (The regulations were eventually thrown out in court and not enforced.) But just 14 percent passed all three — a tiny proportion compared to other publicly traded for-profit colleges, which fared much better. This chart from FinAid.org shows how they did:

How did things get this bad?

The Education Department dealt the college its final blow. But it's been struggling financially for years: Enrollment peaked in 2010, when the company's colleges enrolled more than 110,000 students.

Meanwhile, Corinthian is under investigation from state and federal agencies, including:

- Sixteen state attorneys general working together on for-profit college fraud

- Lawsuits from California and Massachusetts attorneys general over alleged false advertising and lying about job-placement rates

- The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which is investigating Corinthian's student loan business

- The Securities and Exchange Commission

And Corinthian's stock has fallen — and fallen and fallen. At its peak 10 years ago, it traded at $33 per share. On the morning of June 24, the day after reaching an agreement with the Education Department to avert bankruptcy, it traded at 33 cents.

Did the Education Department push Corinthian over the edge?

Corinthian also had serious cash flow problems. And that's what finally almost pushed it into bankruptcy.

Like most for-profit colleges, and many nonprofit colleges without large endowments, Corinthian is heavily dependent on federal money. Including student loans, grants and veterans' benefits, 83 percent of Corinthian's revenue came from the federal government in 2010, according to a report from Senate Democrats.

Usually, when students getting federal grants and loans enroll at a college, the money shows up quickly. The Education Department on Friday put a 21-day delay on sending students' Pell Grants and loan dollars to colleges Corinthian owns, saying the company hadn't responded to inquiries about its job placement rates and marketing practices.

That was enough to cause a crisis. Corinthian is so dependent on federal student aid that even a three-week delay in receiving it would have shut the college down.

On Monday, the Education Department agreed to release $16 million in federal aid — just enough to keep Corinthian operating so that it can plan to sell off or close its campuses in a more orderly fashion.

What happens when a college shuts down or sells campuses?

It's not clear how many of Corinthian's campuses will be sold versus shut down, or whether anyone is interested in purchasing the campuses and continuing to operate them without interruption. (Corinthian itself purchased colleges from other struggling companies in the past.)

The company has to create a plan to allow its 72,000 students to finish their education, and the Education Department will appoint an independent monitor to make sure they can do so without interruption.

But unless the closure and sale are on a very, very slow timeline, this will be a challenge. Some campuses are geographically remote, leaving students with few practical options. There is no guarantee that other colleges will accept their credits, particularly from Heald, Everest or WyoTech campuses that didn't have regional accreditation. And in California, where Corinthian is based and has more than a dozen campuses, community colleges are overcrowded — one reason that for-profits have succeeded in the first place.

Until that plan is in place, the college is still allowed to enroll new students — even though the timeline for selling or closing campuses is fairly quick, certainly shorter than a two-year associate degree.

Corinthian might not be the last

Even as this unfolds — Corinthian plans to sell or close campuses within six months — another for-profit college company is teetering. The Education Management Corporation owns 110 campuses, including the for-profit Art Institutes.

Like Corinthian, EDMC has suffered an enrollment drop-off and its stock has fallen precipitously. It previously warned investors that it may not be able to make a debt payment on June 30; that date has now been extended to Sept. 15. (The idea of a college notorious for students' debt loads struggling to meet its own loan obligations might seem like poetic justice.) The company's future is far from clear.

If it, too, falters, when the Education Department's new regulation on for-profit colleges is finally released later this year, it might encounter a much different corporate landscape.

Corrections/updates: An earlier version of this article referred imprecisely to the gainful employment rule; it's meant to hold individual programs, not colleges, accountable. The date of a potential EDMC default has also been updated.