MI5 targeted the Nobel prize-winning author Doris Lessing for 20 years, listening to her phone conversations, opening her mail and closely monitoring her movements, previously top secret files reveal. The files show the extent to which MI5, helped by the Met police special branch, spied on the writer, her friends and associates, long after she abandoned communism, disgusted by the crushing of the Hungarian uprising in 1956.

MI5 was concerned about her continuing fierce opposition to colonialism, the files, released at the National Archives on Friday, make clear.

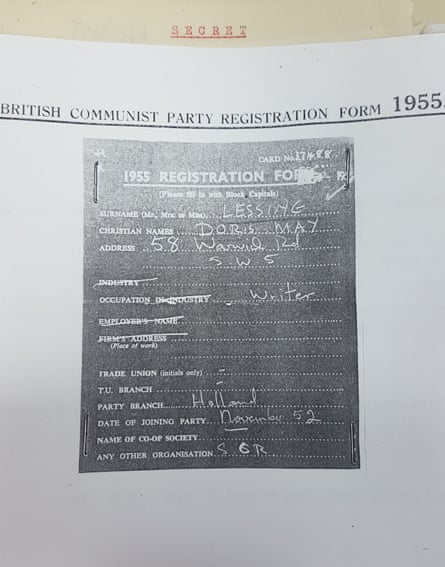

Lessing first came to MI5’s notice in the early 1940s in Southern Rhodesia when, as Doris Tayler, she married Gottfried Lessing, a communist activist and leading figure in the Left Book Club.

She once described marrying Lessing as her “revolutionary duty”. She kept his surname when the marriage ended and she left Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), where she was brought up, and moved to Britain in 1949.

MI5 stepped up its spying on her when, in the course of its permanent bugging of the British Communist party’s headquarters in King Street, Covent Garden, her name (initially misheard as Lacey) came up in a conversation.

In 1952, MI6 passed to MI5 what it called “character sketches” of members of a visit to Moscow by a number of British authors, the files released on Friday reveal. Under the name Miss Doris Lessing, it wrote: “Her communist sympathies have been fanned almost to the point of fanaticism owing to her upbringing in Rhodesia, which has brought out in her a deep hatred of the colour bar.”

MI6 added: “Colonial exploitation is her pet theme and she has now nearly become as irresponsible in her statements as … saying that everything black is wonderful and that all men and all things white are vicious.”

Two years later, MI5 noted that Lessing was “the leader of the Writers Group” of the British Communist party. In 1956, Special Branch informed MI5 that Lessing, whom it described as “of plump build”, had moved into a flat in Warwick Road, London SW5. “Her flat is frequently visited by persons of various nationality,” it reported, “including Americans, Indians, Chinese and Negroes.” The report added: “It is possible that the flat is being used for immoral purposes.”

The special branch later quashed the suggestion, reporting soon afterwards that Lessing had become a supporter of the “European Gathering of Young Women for Peace and Happiness”.

But 1956 proved tumultuous for Lessing. She was banned from South Africa and Rhodesia. Then came Moscow’s violent suppression of the Hungarian uprising. MI5 reported a fraught meeting at the communist party headquarters where Lessing agreed to sign a letter exposing “the grave crimes and abuses of the USSR and the recent revolt of workers and intellectuals against the pseudo Communist bureaucracies and police systems”.

The party’s paper, the Daily Worker, refused to publish the letter, which also referred to “the undesirable culmination of years of distortion of facts”. It was later published by Tribune, the leftwing weekly. Lessing, an MI5 file notes, resigned from the Communist party and rejected an appeal from party officials to change her mind.

Early the following year, 1957, an MI5 source described Lessing as “disgusted with the Russian action in Hungary”, and attacking the attitude of the British communist party as “hopeless and gutless”. The same source described her as “an attractive, forceful, dangerous, woman, ruthless if need be”.

MI5 continued to monitor Lessing’s movements, speeches and writing, and eagerly passed titbits on to the South African police. MI5 officers make clear they chose not to believe that she had “broken completely” with the Communist party, as one file puts it. In 1960, a Special Branch officer told MI5 she attended an “inaugural discussion” of the anti-war group, the Committee of 100, at Friends’ House on the Euston Road, London.

In November 1962, six years after she left the Communist party, an MI5 officer wrote, in a file stamped “secret and personal”: “She is known to have retained extreme leftwing views and she takes an interest in African affairs as an avowed opponent of racial discrimination. In more recent years, she has associated herself with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.”

This is the last entry in the intelligence files on her released on Friday, two years after her death. Official weeders have taken out some pages and passages, partly to protect the name of informants. They may be released at a later date.

In 2007, aged 88, Lessing, who made no secret of her political views, became the oldest winner of the Nobel prize for literature. She died in November 2013, aged 94.

The files released on Friday reveal that MI5 also kept a close watch on prominent figures of the left who were never members of the Communist party. They include the brothers David and Martin Ennals: the former became social services secretary in Callaghan’s 1976 Labour government and was later ennobled, the latter became general secretary of the National Council of Civil Liberties, a founder member of the Anti-Apartheid Movement and secretary general of Amnesty International.

An anxious Foreign Office diplomat wrote shortly after the end of the second world war to Roger Hollis, who later became head of MI5, asking about the pair. MI5 replied that its files on the Ennals brothers had been “in great demand recently”. MI5 was concerned that UN groups, in which it said both brothers were involved, might be infiltrated by the Communist party. MI5 noted that Martin was “well known to Special Branch for his activities in the Anti-Apartheid Movement”.

The MI5 files contain extracts of Harold Laski’s private correspondence that were intercepted because it was worried about his alleged communist connections. His private communications were intercepted, though MI5 reported to the Home Office in 1933 that he was “not a Communist”. Laski was chairman of the Labour party at the time of its landslide victory in the 1945 general election.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion