Titanis walleri

Quick Facts

Common Name: Waller’s terror bird

Titanis walleri belongs to the family Phorusrhacidae, an extinct group of Tertiary birds otherwise known only from South America. Titanis is the only confirmed member from North America.

They were large, predatory, flightless birds that grew to around 5 feet tall.

Several real fossils of Titanis walleri are on public display in the fossil hall of the Florida Museum of Natural History, along with a full-sized interpretation of the skeleton in metal.

Age Range

- Early Pliocene to early Pleistocene epochs; late Hemphillian (Hh4) to late Blancan land mammal ages

- About 5 to 1.8 million years ago

Scientific Name and Classification

Titanis walleri Brodkorb, 1963

Source of Species Name: for Benjamin I. Waller, who along with Robert Allen, collected the holotype and four other specimens of this species.

Classification: Aves, Neognathae, Neoaves, Gruiformes, Cariamae, Phorusrhacidae

Alternate Scientific Name: none

Overall Geographic Range

Gulf Coastal Plain of the United States, with all known occurrences in Florida and Texas. Type locality is Santa Fe River 1, Columbia County, Florida.

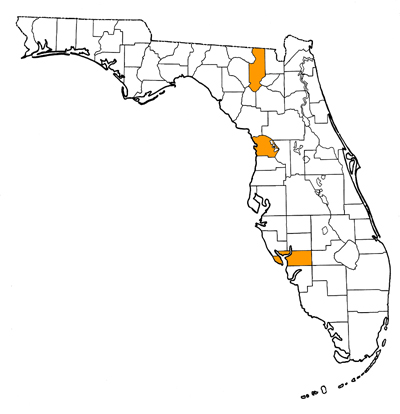

Florida Fossil Occurrences

Florida fossil sites with Titanis walleri:

- Charlotte County—Cocoplum Waterway Canal

- Citrus County—Inglis 1A

- Columbia County—Santa Fe River 1; Santa Fe River 1A; Santa Fe River 1B

- Sarasota County—Dean’s Trucking Pit (not indicated on map)

Discussion

Fossils of Titanis walleri were first discovered in 1961 and 1962 from underwater sites on the Santa Fe River in north-central Florida by two young collectors, Ben Waller and Robert Allen, using scuba gear (Fig. 2). The significance of the fossils and their Blancan age were recognized by then museum curator Clayton Ray (Ray, 2005), who turned the fossils over to Pierce Brodkorb for study. Brodkorb was then a Professor of Biology at the University of Florida and an expert on fossil birds, so this was a logical step on Ray’s part, even though at the time the relationship between museum staff and Brodkorb was not good. As recounted by Ray (2005), Brodkorb ignored Ray’s information about the likely Blancan age of the specimens, dismissing that possibility in the initial publication (Brodkorb, 1963), and instead listed its age as late Pleistocene. Brodkorb also mistakenly thought at first that the bones belonged to a close relative of the rhea and ostrich, and not the South American Phorusrhacidae. Ray’s correction of this error was not acknowledged in the 1963 publication that named the new genus and species.

In the middle 1960s, Florida Museum crews began to extensively use scuba gear to prospect for fossils in Florida rivers, and one of the most heavily collected was the Santa Fe River. Several additional specimens of Titanis walleri were recovered from the Santa Fe River 1A and 1B localities, along with other Blancan species. However, these specimens remained undescribed until the publications of Chandler (1994) and Gould and Quitmyer (2005). Altogether, 27 of the known 42 specimens of Titanis walleri were found in the Santa Fe River.

The second region to produce fossils of Titanis walleri was Inglis 1A, a latest Blancan (ca. 1.7 million years old) filled sinkhole exposed as a result of excavations for the Cross-Florida Barge Canal in Citrus County, Florida. This site was initially excavated between 1969 and 1974 by museum crews and UF students, and resulted in the recovery of 12 specimens of Titanis walleri, including the first known carpometacarpus (Fig. 3), along with several phalanges (Fig. 4) and vertebrae. These specimens were initially described in a Ph.D. dissertation (Carr, 1981) on all of the birds from Inglis 1A, but were never formally published. It wasn’t until Chandler (1994) and Gould and Quitmyer (2005) that their description was published.

The southernmost locality in Florida to produce Titanis walleri is from dredged material along the Cocoplum Waterway Canal in the North Port-Port Charlotte Region of Charlotte County. A single phalanx was found by well-known fossil collectors Lelia and William Brayfield. Blancan fossils are common in this region.

Recently, only the second know tarsometatarsus of Titanis walleri was collected from a shell pit in Sarasota County. Like the holotype UF 4108, this specimen only preserves the distal end of the bone. It is about 10% larger than the holotype.

The only record of Titanis walleri from outside of Florida is a phalanx found in a gravel quarry in coastal Texas near Corpus Cristi (Baskin, 1995). Baskin noted that the quarry produced vertebrate fossils of two different ages, early Pliocene (Hemphillian) and late Pleistocene (Rancholabrean). He favored a late Pleistocene age for the Titanis walleri specimen, assuming that it must be younger than the formation of the Panamanian Isthmus at about 2.5 to 3 million years ago. Gould and Quitmyer (2005) took issue with this and suggested that it could have been eroded out of some as yet unfound early Pleistocene deposit, and thus contemporaneous with the Florida specimens. MacFadden et al. (2007) found that the relative concentrations of rare earth elements in the phalanx matched those from the Hemphillian specimens from the quarry and differed from Rancholabrean specimens. They suggested that the Texas specimen of Titanis walleri is older than those from Florida, and that its dispersal from South America occurred prior to the formation of the land bridge, as is the case for several other species (Woodburne, 2010).

Titanis walleri belongs to the family Phorusrhacidae, an extinct group of Tertiary birds otherwise known only from South America. Phorusrhacids were large, predatory, flightless birds, with over 15 known species. In the absence of members of the mammalian order Carnivora such as canids and felids in the Tertiary of South America, the roles of large terrestrial predators were divided among marsupial mammals, land-dwelling crocodiles, and the phorusrhacid birds. Titanis is the only confirmed member of the phorusrhacids from North America. It was one of the family’ Phorusrhacidae’s largest species (about 5 feet or 1.5 meters tall) and the last member to go extinct. The estimate of its height is taken from the detailed study by Gould and Quitmyer (2005), which is less than some previous estimates. Like other phorusrhacids, it had small, ineffective wings that were incapable of flight. Chandler (1994) hypothesized that the wing of Titanis walleri, while small, was actually robust, strong, and bore a functional claw used in attacking prey. Gould and Quitmyer (2005) found little evidence to support this hypothesis and favored a vestigial, weak wing without a claw.

Several real fossils of Titanis walleri are on public display in the fossil hall of the Florida Museum of Natural History, along with a cast of a reconstructed foot that includes a replica of the holotype. But to make a more prominent display, the museum commissioned sculptor Richard Webber to make a full-sized interpretation of the skeleton of Titanis walleri in metal.

Sources

- Original Author(s): Christina Holland

- Original Completion Date: November 28, 2012

- Editor(s) Name(s): Richard C. Hulbert Jr. and Natali Valdes

- Last Updated On: June 23, 2021

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number CSBR 1203222, Jonathan Bloch, Principal Investigator. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright © Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida