When a new space opens in the world, whether it’s the American West or broadcast television, the early era of exploration takes on a legendary status, a frontier myth, as time passes. Unlike previous undiscovered countries, the men and women of the Internet’s early forays are fated to be part of a narrative remembered more for quirkiness than wildness. Just before the dotcom era crumbled, this reporter remembers one sachem of early tech journalism commenting that only T-shirts and matchmaking sites actually made money online.

There was at least one other venture showing signs that it could work in those days, though: webcomics, the business of posting strips online for free and monetizing once an audience formed. It started in the 80s, with Witches and Stitches and T.H.E. Fox.

Starting in the late ’90s and early 2000s, a small handful of cartoonists were able to turn that success into a living, and some of them were even able to turn it into a very good living. Yet, after the Observer talked to K.C. Green about his decision to end the webcomic that had made him famous, Gun Show, it became apparent that the ground was shifting under this industry.

So the Observer reached out to many of the most widely read webcomics out there. We connected to giants of the field, and they shared insights into the forces that are changing their business and how they are adapting. Nearly everyone that remains is actively diversifying their income streams. Many have deemphasized comics, but we focused on practitioners that haven’t abandoned it.

In four parts, we’ll examine the lessons learned by entrepreneur artists, starting with this broad overview. From business strategy, to paying rent, to trends on the Internet and creative perspective, each part should stand alone, yet fit together.

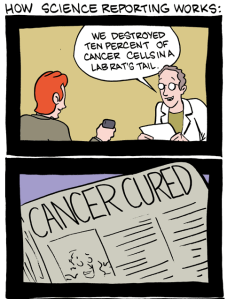

Quality, consistent work is the secret sauce of any content creation online. Advertising and merchandising have been the webcomic industry’s monetization constants since the early days, while social media has proved to be more threat than ally.

Winston Rowntree, the creator of Subnormality, told the Observer via phone that he is doing everything he can to stick to the way he’s always done business since he discovered webcomics. The former zinester said he wants to keep making his as long as he can. “That’s what I think about when I wake up in the morning. My priority is to keep that alive, like watering a plant,” he said. While others might be refining their strategy to keep up with the times, Mr. Rowntree only wants to focus on the quality of the work, adding “Reality has to go to the side.”

Mr. Rowntree’s approach was unique in our discussions. Not only is he not trying to adapt, he’s even eschewing most artists’ monetization standby of going to conventions and selling T-shirts and books. Meanwhile, everyone else we spoke to seemed to believe that their webcomics had created a sort of base of notoriety for them, but also that the less each of them relied on that original source for financial support, the better off they would all be over time.

“‘Webcomics’ is a pretty dated term. I have been a comics professional for 12 years,” John Allison told us via email.

Mr. Allison first started with a comic called “Bobbins” in 1998; he remains one of the most prominent talents posting stories online. He currently posts his comedic paranormal mysteries on his website, Scary Go Round.

How strategy is shifting

“I think I’ve changed my business strategy every year since 2003,” Mr. Allison wrote. “You have to be watching the horizon constantly. The rug has been pulled out from under our feet so many times.”

The consensus among these artists is that new technology has forced change. That said, not all of the strategic corrections artists we spoke to have made were out of necessity. In many cases, they had been looking for new opportunities regardless, as much to grow as creators as to keep roofs over their heads.

Cyanide & Happiness started in 2005. Its table at New York Comic-Con had one of the longest lines we saw. One of its creators, Dave McElfatrick, spoke for a lot of the artists we talked to when he wrote the Observer in an email, via a spokesperson, “Right now, our comics are no longer our primary income stream. They used to be for many years, but since then our business has had to change and adapt to the shifting tides of the Internet—it’s been a difficult transition at times, but we’re still able to do what we love doing, which is the ultimate blessing, really.”

Mr. McElfatrick’s team has moved into animations as well as comics. NBCU will be running Season 2 of The Cyanide & Happiness Show on its new platform, SeeSo, a $3.99 per month comedy video service, he wrote.

The ‘10s seem to be offering creators more possibilities than the ‘00’s did. Yet those are also remembered as boom times, by some. “When webcomics started out, the only way to really get people to pay was by making merchandise, which fostered the T-shirt economy,” Mr. Allison wrote. It ended with the financial crisis, Cat and Girl creator Dorothy Gambrell explained. She wrote, “The business of webcomics rolled along smoothly until the great T-shirt crash of 2008.”

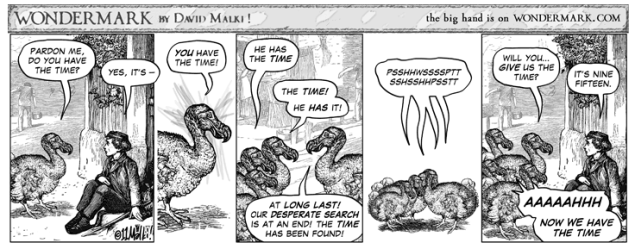

Ms. Gambrell is not the only one who has noticed that printed clothes don’t earn returns like they used to. David Malki, who makes Wondermark but also works for Topatoco, the industry’s favorite distributor of stuff, said the company started looking to provide more than shirts seriously around 2010 or 2011. “Part of that was just realizing that people like lots of things, not just T-shirts,” he told us in a phone call.

For example, the company recently began accepting orders for a “Fat Pony Plush,” a toy based on a favorite character by mainstream breakout Kate Beaton, creator of Hark! A Vagrant.

Meanwhile, Ryan North, the creator of Dinosaur Comics, diversified his business out of boredom. He created Project Wonderful, an advertising service that started with an emphasis on webcomics. Mr. North’s comics don’t require any drawing and seldom even any image manipulation to speak of, yet they were earning him a living when, trained in computer science, he told the Observer that he started the service because he felt underemployed. We’ll go a bit more into Mr. North’s thinking here in our second installment in this series.

The ad service is not the only one he’s started, and he’s also taken on other writing projects for other publishers, recently.

Not everyone has had quite so smooth a ride.

“A hit webcomic in the early 2000s during the online ads boom could become a very healthy living,” Mr. McElfatrick’s said. But web ads are a fickle patron. “Advertising waxes and wanes.” Mr. Allison wrote. In the age of ad blockers, it may almost wholly evaporate.

Between ads and merch, popular webcomics could make a profit or even thrive, until the financial crisis shocked the system, though all of the creators we spoke to seemed to have weathered it well. “I never boomed too much during the boom times so I didn’t bust much during the bust.” Ms. Gambrell, who has always been transparent about her revenue streams, wrote. She opted for a classic approach to diversifying her income stream: a job.

She’s not alone. Mr. Malki said that he’s met a lot of creators who had a great decade in webcomics, but now are looking at working for someone. In a way, he includes himself in that group. He handles Topatoco’s book business (both the ones it publishes and the ones they assist through its crowdfunding fulfilmment service, Make That Thing), a job the skills and contacts he made publishing his own books prepared him for.

The Observer also recently spoke to the two guys behind Amazing Super Powers. They have shifted almost all of their effort over to making video games that share their comics’ outlook, as we previously reported.

Even Topatoco, which was founded by another cartoonist, Jeffrey Rowland, is looking to diversify, seeking work with game makers, podcasters, fine artists and more. “I think Topatoco wants to be in the place where it can provide opportunities to creative people that they may not have thought of before,” Mr. Malki said.

Meanwhile, Drew Fairweather, the creator of the disarming Toothpaste for Dinner and co-creator of Married to the Sea, has largely moved on from webcomics, strategically. “In 2010 I hired a trio of illustrators (located in China) who are insanely great artists, and they’ve illustrated Toothpaste For Dinner since then,” he wrote the Observer.

Webcomics were always just one piece of Mr. Fairweather’s business, a prolific creator of various entertaining media online. From 2003 to 2011, he said, the comics were his most successful part of his business. Today, he’s putting most of his mental energies into writing articles for his blog, The Worst Things For Sale, and and his rap career, as Crudbump (here’s one of his tracks relevant to our coverage).

He keeps the webcomics going, but he said that he’s turned much of the work over to contractors who take ideas he seeds them with.

Meanwhile, Zack Weinersmith of Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal continues to see his webcomic as the backbone of his business, but even he is also trying new ventures. Mr. Weinersmith turned to Kickstarter to fund a new project, Single Use Monocles (We’ll have a lot more to say about Internet funding tomorrow).

How does a monocle business relate to webcomics? As Mr. Malki explained, many of these creators are moving well beyond the intellectual property that made them famous. Ira Glass likes to talk about how Terry Gross once asked composer Philipp Glass if he ever tries to write a song that doesn’t sound like a Philipp Glass song; the composer answered that he tries to do it every time and always fails.

In the same way, everything these creators do will reflect their sensibility, a sensibility that for each one struck a chord in webcomics’ form. If you’ve read very many SMBC strips, a monocle company makes sense in its funny way. In other words, Mr. Weinersmith is, along with many of in his small peer group, letting that sensibility stand—and sell—on its own.

Three more parts in this series will come out over the course of this week:

11/17: Patreon, Webcomics and Getting By

11/18: The Changing Internet Through Webcomics

11/19: Lessons in Creativity from Successful Webcomic Artists

All images used by permission.