Taylonn Murphy is sitting in a Harlem beauty salon after hours. Leaning back in his chair and with a calm demeanor, he is talking about keeping young local people out of harm’s way.

Every now and then though, as he speaks, his voice breaks.

In September 2011, his daughter Tayshana, 18, a local basketball superstar and resident of West Harlem’s Grant Houses, was shot dead by two residents of Manhattanville Houses. The killing was described as the result of a rivalry between the two housing projects that dates back decades.

Almost three years after his daughter’s death, on 4 June 2014, helicopters hovered overhead as the first rays of sunlight hit the concrete. At least 400 New York police officers in military gear raided both housing projects, with indictments for the arrest of 103 people.

Starting in January 2010, the community’s children and young adults had been closely watched by police officers – both online and off. The investigation had involved listening in to 40,000 calls from correctional facilities, watching hours of surveillance video, and reviewing over 1m online social media pages.

For Murphy, the revelation of these details was choking: the NYPD had been attentively surveilling both communities for over one and a half years before his daughter was murdered, patiently waiting and observing as the rivalry between crew members escalated.

Online surveillance: the new stop-and-frisk?

In 2013, stop-and-frisk was found unconstitutional by a federal judge for its use of racial profiling. Since then, logged instances have dropped from an astonishing 685,000 in 2011 to just 46,000 in 2014. But celebrations may be premature, with local policing increasingly moving off the streets and migrating online.

In 2012, the NYPD declared a war on gangs across the city with Operation Crew Cut. The linchpin of the operation’s activities is the sweeping online surveillance of individuals as young as 10 years old deemed to be members of crews and gangs.

This move is being criticized by an increasing number of community members and legal scholars, who see it as an insidious way of justifying the monitoring of young men and boys of color in low-income communities.

These days, crews are understood geographically (“turf-based”). They’re no longer “entrepreneurial” – that is, heavily within the organized crime world, like LA gangs were in the 1990s. In other words, New York City crew membership, which mostly appeals to teenagers, is simply related to the block you grew up on, your community and family ties, and perhaps even your interest in partying, dance or graffiti.

Mostly, being a member of a gang or a crew is a fleeting moment of adolescence, and something that people grow out of, explains Jeffrey Lane, a professor in communication at Rutgers University whose research has looked at the way in which adolescent street life is lived online.

What is unquestionably worrying – and what the NYPD is using to justify broad monitoring of large swaths of people – is when these crews turn on each other, and rivalries between crews become violent, or even deadly. And while some of the humiliation and potential violence is avoided by diverting resources away from the physical practice of stop-and-frisk, online surveillance raises a vast series of questions tied to the civil liberties of young men of color.

A life watched online

Aaron De La Rosa, 24, a soft-spoken lifelong Harlem resident who holds two jobs – one in construction and one in the restaurant industry – says he doesn’t get stopped and frisked nearly as much any more.

There was a time, just a couple of years ago, when he says if he was in a group of five friends or more, they couldn’t make it to the end of a single block without being stopped by police.

De La Rosa says he knows to never post anything related to guns or drugs on Facebook or anywhere else online, even in jest. He is aware, he alleges, that the NYPD is watching him and his friends. He has warned his friends that jokingly posting anything even vaguely incriminating online is dangerous (eg “I wanted to strangle that annoying person on the subway!”).

“But some don’t listen. They’re stubborn,” De La Rosa says, worried.

De La Rosa’s worries are not misplaced. In 2013, Babe Howell, a law professor at CUNY, obtained documents revealing 28,000 New Yorkers were named on a centralized internal NYPD gang list. The list appears to be an open secret among prosecutors and police department workers, and the bars of entry are unclear.

The NYPD juvenile justice division’s “youth crew list” was last leaked to the press in 2012, just before the official launch of Operation Crew Cut. At the time of its release, the list already contained the names of over 300 crews across the city – the most conservative estimate would therefore bring online surveillance to include thousands of youth.

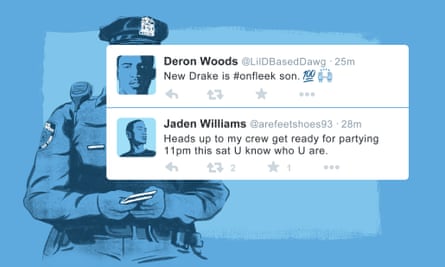

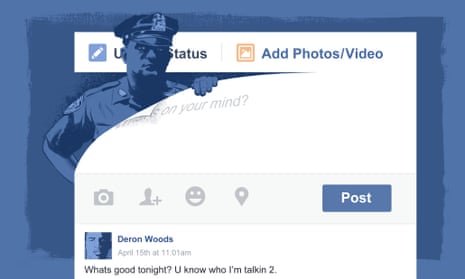

The crews are surveilled offline, but also on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube and other social media channels. When accounts are set to “private”, police officers sometimes gain access to them by sending friend requests posing as young women or club promoters.

As of yet, people added to the gang list are neither notified, nor are they therefore given the possibility of being removed from it. They stay on it for life.

There appears to be no age limitation within the NYPD’s online social media protocol: adult officers seeking to watch alleged crew members as young as 10 by posing as young people are able to do so. There also appears to be no official provision requiring parents or guardians to be notified either.

Bearing direct witness to this widespread online monitoring are the indictments of gang and crew members from the last few years. According to a study by Jeffrey Lane and Fanny Ramirez at Rutgers University, 48% of evidence used in seven separate gang indictments between February 2011 and June 2014 in Harlem related to online social media activity collected through police online surveillance.

Crucially, while crews appear to be referred to as crews when their names are collected for NYPD list purposes, when their members appear on criminal indictments, they graduate to being referred to as gang members. This has heavy consequences in practical and legal terms: bails often skyrocket to impossible levels, and members can be charged as co-conspirators in cases involving, at worst, murders they had no knowledge of and no direct involvement in.

Is racial profiling still at play?

For Dennis Parker, the director of ACLU’s Racial Justice Program, the fact that members seem to overwhelmingly be black and brown youth point to potential racial profiling questions.

“The key to legal policing practices is that you need to proceed on the base of individualized suspicion of criminal activity and that any blanket suspicion on people, either because of where they live or because of their race or ethnicity, is a potential violation of the constitution,” Parker says. “There are ways that you can assure safety in communities, without throwing out these huge nets which capture so many people who are innocent.”

Would a white group of middle-class young men assembled in a college fraternity and stereotyped as being likely to commit sexual assault of women be included on such a list? Current available evidence suggests they would not.

In Harlem, police-community ties have been so compromised by decades of bad relations that residents often do not feel they can call on the police when a crime happens.

De La Rosa, who remembers crying the first time he was arrested when he was 12, says the people he fears the most in the neighborhood by far are police officers, not fellow residents. Even with stop-and-frisk encounters far less frequent, comfort levels are still low. “You can’t even go and hang out in the park with your friends when it’s nice weather. Unless you’re playing baseball, they think you’re up to no good,” he says.

According to Jeffrey Lane, the Rutgers professor who embedded himself in Harlem street life as part of an urban ethnography, police practices sometimes include picking up young crew members on one block, putting them in the back of a police car, questioning them, and then dropping them off, knowingly, in the middle of rival crew territory.

Tayshana’s father, Taylonn Murphy, agrees law enforcement actions do not appear overly concerned with intra-community relations and peace. Despite the fact that two young men were given sentences of 25 years to life for the murder of his daughter in September 2011 (that is, before the raids took place), the case was effectively reopened with the raids.

“What kind of position are you putting my family in that you are locking up 100 kids using my daughter as a premise?” Murphy says, explaining he did not want more arrests, but funding for programs so the community could heal.

“I am lucky people in the community know me and have seen me do good,” Murphy says, referring in part to the reconciliation efforts he has been undertaking across rival crew territories, including with the mother of one of the men convicted in his daughter’s murder. “Otherwise, this would have put me in danger.”

Police proudly point to the fact that there have been no shootings related to the gang rivalry since the raids, something Murphy and his fellow community mobilizer, Derrick Haynes, say is due to the cold weather and a temporary vacuum. “Nothing has been solved,” Murphy says. “You created a void, and you haven’t filled it up with anything.”

Safer now?

Andrew Laufer, a defense attorney in New York City, says he has seen a recent uptick in arrests on mass conspiracy charges made off the back of online social media activity. “They arrest a number of teenagers on a number of serious crimes. Some of them are potentially guilty of them, but most aren’t,” says Laufer, who has represented individuals who were later acquitted in such cases.

Laufer calls the technique both a “roundup” that zooms in on low-income minority communities and a “numbers game”, alluding to the fact that the police department may be looking to make arrests to meet high quotas of fines or arrests.

Mike Loudwy, a South Harlem resident, does not feel any less targeted than he used to. This, despite the fact that illegal activity in Harlem is nowhere near what his older peers tell him it once was. “Drugs are sold out. No one is selling. The game is much safer now. So of course they [the police] are going to find something new to go after,” he says. “The only reason they were raiding that thing [the Grant and Manhattanville houses] is because they can’t catch nobody no more.”

CUNY law professor Babe Howell backs this point up. “Violent crime has declined 80% in the last two decades. Law enforcement doesn’t have much to do. So they’re creating a world in which we are fearful of gangs, and then creating accomplice liability, so that there will be one shooting but we will hold 50 kids accountable for it.”

But when Operation Crew Cut was launched in 2012, the justification for it was that while crime had gone down, it had not gone down in specific pockets of the city, where crews and gangs were running rampant.

While not completely exonerating, actual data may suggest a more complex, less alarming story. In a forthcoming article on the subject, Howell finds that, looking at NYPD crime statistics from every year between 2005 and 2012, the amount of gang-motivated crime in fact only accounts for less than 1% of total crime (close to 0.2% most years, except for 2012 when it was 0.09%).

As for shootings and homicide, the numbers are higher, but still vastly below the 30% or one-third repeatedly advertised by former police commissioner Ray Kelly and current police commissioner, Bill Bratton. Direct gang-related shooting and homicide incidents each mostly hovered around 3% in respective categories over the eight-year period analyzed. Gang-related homicides and shootings were considerably higher, but still well below publicized numbers, ranging from representing 12% and 19% of shootings, and between 15% and 20% of homicides.

According to NYPD charts from 2011 and 2012 where both categories are included, domestic violence is between two and four times more likely to be a cause for homicide than gangs are.

A recipe for injustice

Large cities like Detroit, Chicago, Washington DC and Los Angeles are also experimenting with online social media monitoring, with children as young as three sometimes being found on databases. The Detroit Crime Commission has been seeking to develop algorithms able to cut through millions of tweets to zoom in on those pointing to violent acts or intent.

Desmond Patton, a social work professor at the University of Michigan, says with the right kind of cooperation between law enforcement and people in the know, such as violence interrupters, online social media monitoring could be used to foresee and interrupt violence, rather than just crack down on it.

But Jay Stanley at the ACLU says “wholesale mongering” – or watching people on a mass scale, even when the monitored information is publicly available – is an unacceptable practice.

“Yes, any police officer can read the New York Times, but we are not paying our police officers to read the New York Times, we are not paying police officers to monitor our social media streams,” Stanley says.

“Our technology has created such a risk trail of information about us. At a time where we are also seeing prosecutorial powers and discretion expanding, and privacy protections being eroded. When those three trends dovetail, it’s a recipe for injustice.”

‘They know everything we do’

Mike Loudwy is sipping on a strawberry margarita at one of Harlem’s underground Mexican restaurants. He is comparing notes with his friend about police treatment of black people in the area. The tone is good-humored with a hint of the incensed.

“You can get caught being black on a Friday night and be thrown into jail,” Loudwy quips. Many of his friends are locked up, he says – some for as little as being found with $30 worth of drugs on them. His dinner companion, also a young black Harlem resident, starts counting off the NYPD cameras installed in streets surrounding their homes. “I’m telling you, they’re watching us, man. They know everything we do.”

While ordering some food, Loudwy confides the best way to deal with police randomly stopping you is to stay silent and know your rights. “If you start talking, they’ll find a way to throw you in. Any wrong move could be my life,” he says. “You don’t even have to let them search you. They need a probable cause.”

Loudwy says he learned about his rights by watching a series of videos on YouTube. Technology is changing things, he explains, pointing to the way in which Eric Garner’s killing at the hands of police last summer was filmed and widely shared online.

Is he on Facebook? “Hell no. I call Facebook ‘fed-book’. I don’t do Facebook. They’re watching us on there.”

To some, his words may come across a little paranoid; the result of growing up with cameras on the street corner, police watchtowers a few blocks away; too many years being ordered to the ground by an overzealous police force. Maybe a few too many Snowden-themed movies, too.

And yet, Loudwy’s fears hold up. What is perhaps most alarming is that he and his friends are so used to being treated like suspects that to find out that they are being watched online comes as no surprise. Even without actual proof, it’s something they have just assumed – quite rightly – has been happening all along.

The NYPD was contacted for interview on this story, but declined to make anyone available.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion