Television ads for erectile dysfunction, stroke or toenail fungus treatments have been called both a boon and a curse. Drugmakers assert that promoting their products makes patients aware of conditions they can then flag for their doctor.

Yet every developed country except the U.S. and New Zealand prohibits such direct-to-consumer prescription drug ads. It is hard to see educational value in commercials on American TV that show radiant models relaxing before a tryst, accompanied by voice-overs that warn of possible side effects, including difficulty breathing and an unsafe drop in blood pressure.

An ad that conflates an aura of glowing health and the prospect of an amorous liaison with a list of dire cardiovascular symptoms is a paradigm of confused messaging because it does not provide the viewer with a clear guide to weighing both benefits and costs entailed in using a prescription medicine. Absent further interpretation, the underlying message reduces to: Sex or death—which will it be? Of course, the ads always end with an admonition to “ask your doctor....”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

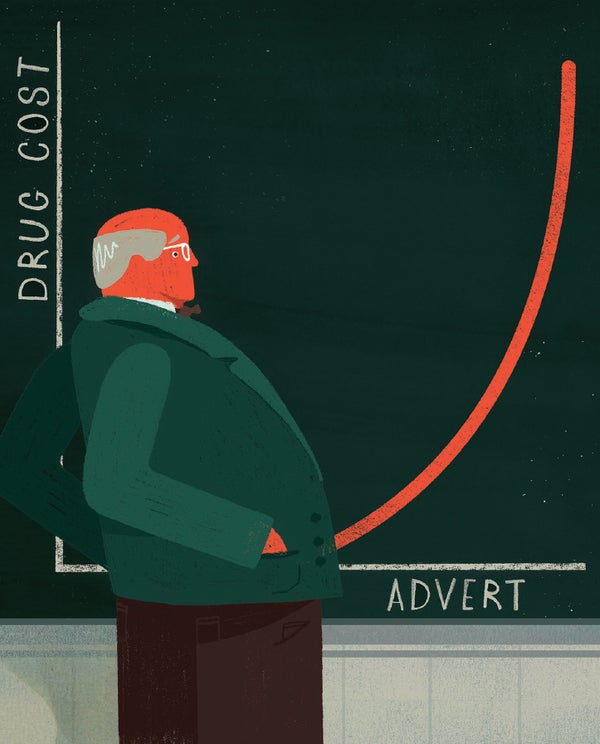

Now, finally, the doctors are giving an answer. In November 2015 the American Medical Association asked for a ban on these ads, saying that they are partially responsible for the skyrocketing costs of drugs. The World Health Organization and other groups have previously endorsed such restrictions.

In 2014 pharmaceutical companies spent $4.5 billion on consumer ads, mostly for television, a 30 percent rise from two years before. The pitches can drum up sales on higher-priced medications that can drive up drug costs when less expensive alternatives are sometimes available.

Many of the newest ads are for premium drugs for life-threatening diseases or rare conditions that can cost tens of thousands of dollars and require large, out-of-pocket patient co-payments. After seeing an ad, patients may press physicians for a prescription without understanding the complex criteria needed to determine eligibility for treatment.

Despite industry rhetoric about educating the consumer, the ads do what ads do—promote the advertiser's product while failing to note these complexities or alternative options. Last October a Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that 28 percent of people who viewed a drug ad subsequently asked a physician about the medicine and that 12 percent walked out with a prescription.

A ban would be a welcome step toward trimming the nation's lofty drug bills—and it would rid the airwaves of purported health messages that baffle more than they inform. It is unclear, though, whether any prohibition passed by Congress would pass muster in the courts. Pharma would undoubtedly mount a legal challenge, claiming that the law violates First Amendment protections for commercial speech.

Steps, however, can be taken short of outright prohibition. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton, who has highlighted inflated drug prices as a campaign issue, wants to eliminate the industry's ad-based tax deduction. There are other options as well. Because drug companies contend that the ads are an educational tool, the Food and Drug Administration might hold them to their word. They could be required to focus consumer ads on the benefits of a particular class of drugs rather than a specific product. The patient could then follow up with a physician who might recommend, say, the best diabetes medicine.

Another constructive move would be for Congress to pass the Responsibility in Drug Advertising Act, introduced in February by Representative Rosa DeLauro of Connecticut. The bill would require a three-year moratorium on ads for new prescription drugs approved by the FDA.

The proposed legislation also could be flexible in its implementation. The bill recognizes that a new approval by the FDA can have substantial public health benefits, and so it provides for the waiving of the restriction case by case. And it would permit extending the ban beyond the three years if concern over a side-effect profile persisted. A break from the up to 30 hours of prescription drug ads that the average TV viewer is exposed to every year—be it temporary or permanent—would be a refreshing relief.