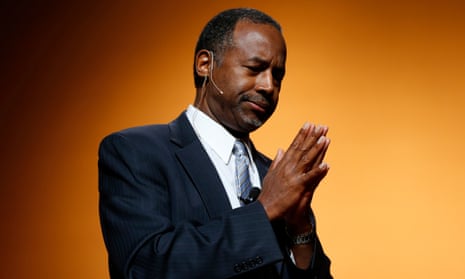

When Donald Trump blasted to the top of the presidential polls in July, it became clear 2016 would be a very unusual election cycle for Republicans trying to nominate someone to win back the White House.

Then things got stranger. Trump fell out of first place, nudged aside by a candidate who is his temperamental opposite but resembles the mogul in one crucial aspect: Dr Ben Carson, a soft-spoken retired pediatric neurosurgeon, has zero background in politics.

So far, the voters love him for it. Carson’s favorability rating among Republicans, at 74%, towers over the field. His devout Christianity has made him a darling among evangelicals, who count for about a third of caucus participants in Iowa, the first state to vote. And in the last quarter the Carson campaign reported contributions of $20m, more than any of his rivals.

Carson now faces a key test, with the Republican candidates convening on Tuesday in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, for their fourth presidential debate. Leading in the polls, Carson will be under new pressure to convince voters he belongs there. A solid outing could bring him closer to an Iowa victory and give him real momentum.

But does Ben Carson really belong there?

He is more than an American success story, brilliant brain surgeon and bestselling author of 10 Christian-themed books. He has also coined some of the most outlandish statements ever uttered on the national stage, a purveyor of bizarre conspiracy theories and a provocateur who compares abortion to slavery and same-sex marriage to pedophilia.

This week, Carson restated his belief that the pyramids were built by the biblical Joseph to store grain, and not by Egyptians to entomb their kings. He believes that Vladimir Putin, Ali Khamenei and Mahmoud Abbas attended school together in Moscow in 1968. He believes that Jews with firearms might have been able to stop the Holocaust, that he personally could stop a mass shooting, that the Earth was created in six days and that Osama bin Laden enjoyed Saudi protection after 9/11.

Democrats and social liberals recoil, but his unpredictability – and at times an inexplicable callousness – has also alarmed Republican party headquarters.

The “political class” – a top Carson phrase – fears him, he says, because he threatens to interrupt business as usual.

The Carson conundrum is not fully captured by a list of his eccentric beliefs, however. He also confounds the traditional demographics of US politics, in which national African American political figures are meant to be Democrats. Not only is Carson a Republican – he is a strong conservative on both social and economic issues, opposing abortion including in cases of rape and incest, and framing welfare programs as a scheme to breed dependence and win votes.

He has visited the riot zones of Ferguson and Baltimore but offered little compassion for black urban poor populations who feel oppressed by mostly white police forces.

Even Carson’s core appeal as a Christian evangelical is complicated by the fact that he is a lifelong adherent to a relatively small sect, the Seventh-Day Adventist church, whose celebration of the sabbath on Saturday instead of Sunday and denial of the doctrine of hell have drawn accusations of heresy from other mainstream Christian groups.

The Adventists’ credo was shaped by the “Great Disappointment” of October 1844, when the second coming notably failed to come to fruition as hoped. For Carson, rocked on Friday by an admission that he had invented a story about being offered a full scholarship to West Point military academy, the challenge is to avoid a similar epithet being attached to his political career.

In Baltimore, where Carson was a top pediatric neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins hospital for 30 years, he seems to inspire both reverence and unease.

Quantae Johnson was just four years old when he met the doctor, after being caught in the crossfire of a gunfight between rival gangs on a summer night in 1991.

“I was sitting in the house with my grandmother, because the neighbors were saying, ‘Tell the kids to go in the house because it’s about to get wild out here’,” Johnson, 28, said this week on the stoop of the home where he lives with his mother in east Baltimore. “I went in the house and jumped in my grandmother’s lap.”

Then the firing started.

“The bullet went through a wooden cross inside a window. It cut through that wooden cross, slowed it down a little, before it impacted my head, going through my brain.”

Johnson’s grandmother picked him up and started running, headed for the emergency room at Johns Hopkins hospital, two blocks away.

“My head was gushing. My grandma was running me to the hospital.”

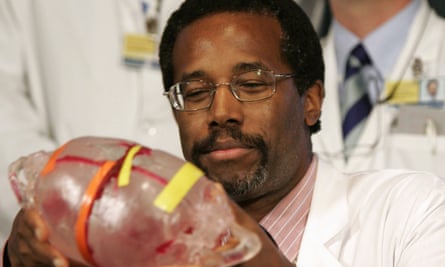

Carson, who in some years performed more than 500 pediatric brain surgeries, received the patient. The bullet had not touched any of the lobes controlling speech or movement. Less than two days later, the boy was joking with doctors and could name all four Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. He became known as Little Miracle Man. Today, Johnson said, he suffers from occasional seizures, but otherwise has no residual impairments.

Johnson supports Carson’s presidential bid.

“I believe he would put the right people in positions, who he perceives were good enough, and that would work out,” Johnson said. “He’s a very inspirational person to look up to.”

Johnson said gun violence in Baltimore had only grown worse since he was shot in the head, and that the city needed more jobs. He said that his own access to medical care “could be better” and that he had stopped taking an anti-seizure medication because the side-effects interrupted his work as a home improvement contractor.

But Johnson had faith in Carson’s ability to address the problems of hard-hit communities, he said, because that’s where Carson comes from. The surgeon’s mother, Sonya Carson, was one of 24 children who was forced into marriage as a teenager and who left her husband after discovering he had a second family. She raised Carson and a brother in poverty in Detroit and then in Boston, working multiple jobs and requiring her sons to read two books a week although she herself was nearly illiterate.

“It seems we don’t have too many people who know about the adversity, and about coming from the bottom row, and seeing it all the way through, and having a vision of a better world, a better outcome,” Johnson said. “And I believe he has that in his mind.”

While Sonya Carson worked hard to avoid what she considered the dangers of government assistance, she occasionally relied on food stamps and other programs to raise Ben and his older brother, Curtis. Carson’s subsequent opposition to welfare programs has left him open to accusations of insensitivity at least, or worse, hypocrisy.

He rebuts the charge in his latest bestseller, A More Perfect Union. “Of course, the progressives will ignore the facts and claim that I am advocating eliminating all governmental safety nets,” he writes. “They will say now that I have ‘made it’, I want to pull up the ladder and keep others from benefiting. This kind of nonsense is typical of the scare tactics they use to maintain support for their failed policies …”

Carson has called for more support of private charities, and runs a highly successful one, the Carson Scholars Fund, which started in 1996 and now awards more than 500 students annually with $1,000 in college tuition. The fund also finances the construction of “Ben Carson reading rooms” for children.

What is indisputable is that Carson has, as he puts it, “made it”, having accrued a fortune from book sales, motivational speeches, positions on the boards of corporations including Kellogg’s and Costco.

In 2001, Carson and his wife, Lacena “Candy” Carson, placed a substantial share of that wealth in real estate, buying a 48-acre property outside of Baltimore in rural Maryland, that boasted Georgian décor, interior corinthian columns with gold-leaf capitals, a palace staircase, eight bedrooms and 12 bathrooms. His mother Sonya lived in the home with the couple and their three sons; the family now mainly resides in Florida.

Numerous profiles of Trump in the last four months have noted his “me-wall”, his in-office shrine to himself. In Carson’s Maryland home, the “me-wall” was a “me-basement”, the walls covered with plaques. Upstairs, Carson’s Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, had pride of place near the front door. A painting of Carson in a surgeon’s coat hung over a mantle where a misspelled Bible verse was engraved. On another wall was a painting of Carson with Jesus Christ – his hand on Carson’s shoulder.

Carson believes in God. But he also believes in himself. One of Carson’s defining moments as a brain surgeon was his decision to attempt a hemispherectomy, the removal of half the brain, to treat a child who suffered from hundreds of chronic seizures a day.

It had been decades since the procedure had been attempted. The consensus of peers said it was dangerous and ineffective. Carson decided to investigate for himself, reading deeply and consulting with colleagues – and then he decided to try it. He rehabilitated the procedure, ultimately salvaging dozens of lives.

Repeatedly in his career, Carson excelled by ignoring others’ advice about what was possible and what was impossible. He distrusted reputed “expertise” and found his own way, often brilliantly. So it is that when confronted on the campaign trail by an issue he hasn’t thought deeply about, such as one aspect of the US policy on Cuba, which stumped him last week, he does not register discomfort.

“I have to admit that I don’t know a great deal about that,” he said, “and I don’t really like to comment until I’ve had a chance to study the issue from both sides.”

On Wednesday night inside the United in Christ Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) church, within walking distance of Johns Hopkins hospital Pastor Gary Adams and two church elders, Greg Manning and Parris Mitchell, sat talking about Ben Carson and the challenges that confront members of congregations like theirs.

While the congregation has been shrinking in recent years, United in Christ is a linchpin for the community offering free food on Wednesday afternoons. That night’s prayer service drew only about a dozen worshippers, however.

They heard a sermon about end times and the need to support those in prison, nursing homes and broken homes. They gave voice to their own prayers, asking God to work his will in a daughter’s troubled marriage and asking protection for “the children and grandbabies”. When the prayer meeting was through, everyone hugged everyone.

“The Seventh Day Adventist church does not support or endorse any politician or political party,” said Mitchell afterward. “We don’t endorse anybody.”

Carson had never visited the church, but he was well known, even beloved in the area, Adams said, for his work as a doctor and his charitable efforts. But the three men expressed reservations about Carson’s social views, and his hard line on social welfare programs.

“[Carson] shouldn’t forget where he came from,” said Adams. “How he came up. He should have a better understanding about people’s struggles.”

In Baltimore City, those struggles include excessive use of force by police, poverty, a lack of jobs, anger and frustration. Thirty-five percent of children in the county live in poverty, and the unemployment rate for black men ages 20-24 is 37%, according to the latest US census data

“I would say that 80 to 90% of the people we baptize into this church are poor people,” Adams said. “And we know that because we have a Lift the Burden fund, and people get into situations where they need financial help, so most of the people we baptize are poor people. And if they cut all of those programs out” – he shook his head – “Oh my goodness. My goodness.”

The three men said the community needs opportunity, attention and help.

“You hear it all the time, these individuals, they come in and they talk about, they’re going to ‘downsize the government’,” said Mitchell. “If you downsize the government, you cripple too many communities.”

“As far as what Dr Carson has done with the Carson scholarships, and his medical profession, it’s admirable, his record speaks for itself,” Manning said. “That’s why people love him, that’s why people respect him. But as far as politics, I can’t really say that people follow him for his political views.”

Adams summarized his view with a line in an email.

“I am disturbed by some of his comments that he has made,” he wrote. “As a physician he was great. As a politician, I have no faith in his ability to run the country.”

Ben Carson’s CV at a glance

Name: Benjamin Solomon “Ben” Carson

Age: 64. Born 18 September 1951, in Detroit, Michigan

Education: BS in psychology, Yale University, 1973; MD, University of Michigan, 1977; residency in neurosurgery, Johns Hopkins hospital

Career: At age 33 became chief of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins hospital, and the youngest-ever head of department.

Led team of 70 to separate twins conjoined at the head in the first-ever surgery of its kind.

Pioneered life-saving brain surgery techniques including hemispherectomies to treat seizure patients.

Achievements: Presidential Medal of Freedom, nation’s highest civilian honor, awarded by George W Bush in 2008

Gifted Hands, the bestselling memoir of his journey from an impoverished childhood to the pinnacle of professional success, adapted for 2009 movie starring Cuba Gooding Jr.

Famous for: Trashing Barack Obama’s healthcare law to the president’s face at the 2013 national prayer breakfast

Key Quote: “My own personal theory is that Joseph built the pyramids in order to store grain.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion