Employees work at strengthening the Mosul Dam in northern Iraq, February 3, 2016.

Azad Lashkari/REUTERS

Iraq, is facing an unprecedented threat from the giant Mosul Dam, upstream from its biggest cities, which U.S. experts warn is in danger of bursting and unleashing a catastrophic tsunami-like wave.

The country, under attack from Islamic State extremists and still reeling from a U.S. invasion and sectarian war, must now contend with a scenario that could be more deadly than all of these combined.

The U.S. embassy in Baghdad has warned that the 31/2-kilometre-long earthen dike holding back more than 11 billion cubic metres of the Tigris river "faces a serious and unprecedented risk of catastrophic failure."

Should it blow, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers says, it would create a wave some 25 metres high that would race down the middle of Iraq's most populated and developed areas sweeping downstream anything in its path, including bodies, livestock, buildings, cars, unexploded ordnances and hazardous chemicals.

The embassy report warned it "would result in severe loss of life, mass population displacement and destruction of the majority of the infrastructure within the path of the projected flood wave."

Studies by U.S., Iraqi and European engineers estimate that between 500,000 and 1.5 million people would likely be killed by such a flood and its aftermath. It would be "a humanitarian catastrophe of epic proportions," Samantha Power, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, said last month as she called on UN member states to press for "urgently needed" action.

Earlier this year, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry is reported to have delivered a confidential note to Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi from U.S. President Barack Obama. In it, the U.S. leader is said to have pleaded with Mr. al-Abadi to take immediate action to protect the lives of the many Iraqis at risk.

The President's personal intervention makes it clear Washington fears a breach in the dam may be imminent and would jeopardize efforts to stabilize the Abadi government and confound the war against the Islamic State.

The Mosul Dam was largely a vanity project ordered by Saddam Hussein in 1981, even as the Iran-Iraq war was raging. It was finished and put into use in 1986, providing electricity to more than two million people in Mosul and the surrounding area.

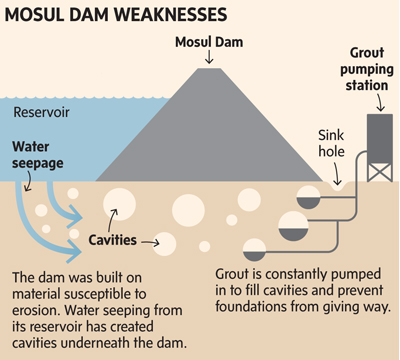

The problem, however, is that little thought was given to its location and it was constructed atop a bed of gypsum, a mineral that dissolves in water.

In August, 2014, Islamic State forces overran the area and took charge of the dam. The dam workers fled.

Alert to the possibility that IS fighters might sabotage the dam, a joint force of Iraqi Kurds and Arabs regained control of the structure and continue to jointly guard it against IS forces only a few kilometres away. The IS fighters, however, looted the facility before they left, taking with them much of the grouting equipment and leaving the dam vulnerable.

Sensors planted by U.S. Army engineers in December show growing crevices in the gypsum base that holds up the earthen dike.

Despite the warnings, however, little has been done to safeguard the people, the infrastructure, the industry and the farmland that are at stake.

Meanwhile, the spring runoff from the mountains north of the dam is beginning to build on the Tigris.

"The dam is in a very dangerous situation now," said Dr. Nasrat Adamo, who oversaw the dam for several years until 2014. The floods of March and April "will definitely raise the water to alarming levels," he told the BBC. "My feeling is the dam will fail some time in the [near] future."

"If this dam were in the United States, we would have drained the lake behind it," Lieutenant-General Sean MacFarland, commander of U.S. forces in Iraq, told reporters in Baghdad when the embassy warning was released on Feb. 29.

To make matters worse, the embassy noted, the underwater safety gates that can be opened to release water and reduce pressure are not working properly.

Iraqi officials have known about the dangerous situation with the gypsum base since before the completion of the dam. As early as 1984, Swiss consultants retained by the Iraqi government cautioned it would be a serious problem and they warned of the disastrous consequences of a breach.

An Iraqi Kurdish Peshmerga stands guard near the Mosul Dam in northern Iraq, February 3, 2016.

Azad Lashkari/REUTERS

Their report was kept a closely guarded secret while officials dismissed any suggestion of possible leaks. They utilized hundreds of men and special grouting equipment to pump cement into the fissures on a daily basis to mend the cracks.

The constant grouting held it together for a number of years. (Known then as the Saddam Dam, the regime made sure the structure got all the attention it needed.)

When the U.S.-led invasion forced Mr. Hussein from office, U.S. Army engineers took charge of the massive dam and knew to continue the extensive grouting. When handing it back to Iraqi control in 2011, they warned that "a failure of the Mosul Dam could cost 500,000 civilian lives in the immediate aftermath."

Iraqis kept up the maintenance, too. But now, with the war against the Islamic State so close, the Iraqi authorities seem unable to get sufficient equipment or workers to properly maintain the site.

The approximately 1.5 million Iraqis residing along the Tigris are at the highest risk from the flood wave and will require prompt evacuation orders if they are to survive, experts warn.

Nadhir al-Ansari, an Iraqi-born professor of geotechnical engineering and water management at Lulea University in Sweden, wrote in November that he had reviewed all the scientific research on the dam and found broad agreement on the impact of such a flood wave.

On the first day, Mosul would be hit hard and suffer the direst consequences, Prof. al-Ansari wrote, and residents would have to move at least six km from the current banks of the Tigris to avoid the flood wave.

On the second day, residents of Tikrit would need to retreat at least five km from the riverbank to be safe, while Samarra residents on the west bank of the Tigris probably could reach safety by moving about six km away from the river bank.

Those living on the east bank, however, would need to flee farther – probably around 16 km – to avoid being cut off by multiple channels of water when the major irrigation canals flood.

By the third day, flood waters would reach Baghdad, leaving many parts of the capital, including Baghdad International Airport, beneath half a metre of water, with the airport unusable.

Because the Baghdad area is so flat, the water settling there would likely remain for several weeks or even months, making a return to normality greatly delayed.

Timely and effective evacuation warnings are essential to save hundreds of thousands of lives, U.S. officials have emphasized.

Employees work at strengthening the Mosul Dam in northern Iraq, February 3, 2016.

Azad Lashkari/REUTERS

In the north, in particular, there is only a narrow window between the time a breach is detected and the impact of a flood wave. To make matters worse, the Mosul area remains largely under the control of Islamic State forces, who may not carry out methodical retreats from the river, perhaps fearing that their enemies – the U.S.- and Iranian-backed Kurdish and Arab Iraqi forces – would use the opportunity to retake Iraq's second-largest city.

Communities further downstream may have greater warning but, by then, Iraq will be subject to widespread, perhaps nationwide electrical blackouts, making communication difficult and movement slow.

In many areas, officials note, people may not grasp the urgency and scope of the threat they face and will be too slow to respond. Indeed, populations living anywhere in Iraq's politicized media environment may find warnings of a tsunami-like wave difficult to believe and likely are unaware of the possibility, scale and quickness of flooding that would result from a breach.

"The Flood is how civilizations rise and fall in Iraq," said Michael Knights, an Iraq specialist at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. "It is a recurring theme in Iraqi history." But, he added, the "probability of the Mosul Dam breaking is very low."

Should it break, he acknowledged, it would have "a very high impact." But the U.S. and Iraqi governments are co-operating on this issue, he says, and he believes they will be able to avert a breach in the dam.

What will happen if the dam fails

If a breach were to occur, it would start with the collapse of the dam's porous foundation, then quickly spread and wash away much of the earthen dike. An inland "tsunami" more than 25 metres high would rush downstream at about 20 kilometres an hour.

Mosul

Within four hours, much of the city of Mosul, nestled in the Tigris River valley, would be under water. Only those who fled the flood zone would be likely to survive. To escape the water, residents would need to move back about six kilometres from the riverbank.

Much of this area is controlled by Islamic State, so an evacuation directed by the authorities is unlikely and some evacuees would not have the freedom of movement needed to escape.

The flood wave would carry bodies, automobiles, livestock and unexploded bombs downstream. (About 15 centimetres of moving water can knock a person off his feet and 40 centimetres can carry away most automobiles.)

Central Iraq

The wave would reach the cities of Tikrit and Samarra within 25 hours, covering larger expanses in the flatter terrain.

To be safe, residents of Tikrit would have to move back about five kilometres from the riverbank.

Residents of Samarra on the west bank of the Tigris would need to move back at least six kilometres from the riverbank. Those on the east bank would need to move 16 kilometres away to avoid being cut off by flooded irrigation canals.

Samarra's historic sites, such as the ninth-century spiral minaret and the shrine of the 10th and 11th Shia imams, could be damaged or washed away, as would be many homes and businesses.

The capital

Floodwater would reach Baghdad within 48 hours, with a depth of as much as 10 metres in the river channel. Much of the city, including the international airport, would be under as much as 50 centimetres of water.

A majority of Baghdad's 6.6 million residents would be adversely affected – experiencing dislocation, increased health hazards, limited mobility and the loss of homes, buildings and services.

Although water in areas north of Samarra would likely recede quickly, Baghdad would experience several weeks or months of standing water, which would delay recovery efforts.