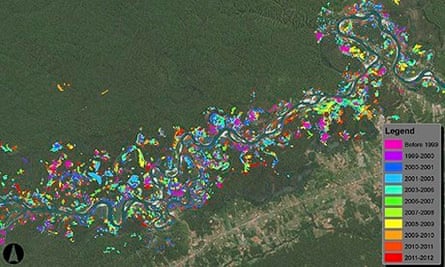

The area affected by illegal gold mining in Peru's south-eastern Amazon region increased by 400% from 1999 to 2012, according to researchers using state-of-the-art mapping technology.

Using airborne mapping and high-satellite monitoring, researchers led by the Carnegie Institution for Science also showed that the rate of forest loss in Madre de Dios has tripled since the 2008 global economic crisis, when the international price of gold began to rise to new highs.

Until this study, thousands of small, clandestine mines that have boomed since the economic crisis went unmonitored, according to the research team, which was led by Carnegie's Greg Asner and worked with Peru's environment ministry.

Crucial technological differences, such as the use of the Carnegie Landsat Analysis System-lite (CLASlite), meant the team was able to map both large and small mining operations.

"The gold miners are working in thousands of small groups, so it takes our high resolution techniques to map their activities," said Asner, who developed the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), technology that uses algorithms to detect changes to the forest in areas as small as 10 square metres (about 100 square feet), allowing scientists to find small-scale disturbances that cannot be detected by traditional satellite methods.

The team collated the satellite results with on-ground field surveys and CAO data. The CAO uses light detection and ranging, a technology that sweeps laser light across the vegetation canopy to produce a 3D image. It can determine the location of single standing trees at a 1.1 metre (3.5 feet) resolution. The field and CAO data confirmed up to 94% of the CLASlite mine detections.

"Our results reveal far more rainforest damage than previously reported by the government, NGOs, or other researchers," Asner said.

"In all, we found that the rate of forest loss from gold mining accelerated from 5,350 acres (2,166 hectares) per year before 2008 to 15,180 acres (6,145 hectares) each year after the 2008 global financial crisis that rocketed gold prices."

"The gold rush in Madre de Dios, Peru, exceeds the combined effects of all other causes of forest loss in the region, including from logging, ranching and agriculture. This is really important because we're talking about a global biodiversity hotspot. The region's incredible flora and fauna is being lost to gold fever."

In addition to wreaking direct havoc on tropical forests, gold mining releases sediment into rivers, with severe effects on aquatic life. Another recent study showed that gold mining has contributed to widespread mercury pollution, affecting the entire food chain but particularly impacting on indigenous populations.

Ernesto Raez Luna, an advisor with the Peruvian environment ministry and co-author of the report, said: "Obtaining good information on illegal gold mining, to guide sound policy and enforcement decisions, has been particularly difficult so far. Finally, we have very detailed and accurate data that we can turn into government action.

"We are using this study to warn Peruvians on the terrible impact of illegal mining in one of the most important enclaves of biodiversity in the world, a place that we have vowed, as a nation, to protect for all humanity. Nobody should buy one gram of this jungle gold. The mining must be stopped."

As of 2012, small illicit mines accounted for more than half of all mining operations in the region. Large mines are heavy polluters but are taking on a subordinate role to thousands of small mines in degrading the tropical forest throughout the region.

The research is published in the online early edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion