In his Arthur Miller Freedom to Write lecture, delivered in New York in 2007 – a lecture that should be read by anyone interested in undertaking the emotional labour of making any kind of true art – the great Israeli novelist David Grossman said: "The consciousness of the disaster that befell me upon the death of my son Uri in the second Lebanon war now permeates every minute of my life. The power of memory is indeed great and heavy, and at times has a paralysing effect. Nevertheless, the act of writing creates for me a 'space' of sorts, an emotional expanse that I have never known before, where death is more than the absolute, unambiguous opposite of life." Falling Out of Time is the work of space and expanse produced in the aftermath of Grossman's terrible loss. It is not perhaps his best novel, because it is not a novel: it is a work of mourning. One of Grossman's earlier books was called The Book of Intimate Grammar: this is his Intimate Book of Grief.

On the page the book resembles a play, or a prose poem, possessing at times the qualities of a religious or mystical text – wandering, sprawling, repeating itself like a cry or a prayer, returning again and again to questions about the meaning and nature of loss. Comparable books are perhaps Imre Kertész's Kaddish for an Unborn Child, or the much-overlooked and underrated works of Charles Reznikoff: works of recitation and testimony. Characters give speeches; there is much rumination and reflection; but Grossman is also a storyteller, and Falling Out of Time does not entirely fall out of time. It goes inward, and around, but it also goes forwards. It has a narrative that reads as much like a parable as an autobiography.

An unnamed man announces to his wife one day that he is leaving to go "there", to find their dead son:

I have to go.

Where?

To him.

Where?

To him, there.

To the place where it happened?'

No, no. There.

What do you mean, there?

I don't know.

You're scaring me.

Just to see him once more.

But what could you see now? What is left to see?

I might be able to see him there. Maybe even talk to him?

Talk?!

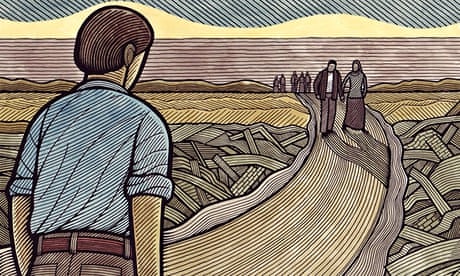

And so the man sets off and begins walking, circling his town; he becomes simply "the Walking Man". He is seeking a way out of the void, through the void. On his journey, he meets others – the cobbler, the midwife, the net-mender, the elderly maths teacher, the duke, the town-chronicler and his wife – who have also lost their children and who are also lost in grief. They walk together and begin to share an identity. They become a kind of entity – the "Walkers". At times they are guided by a fire – "a small fire, the constant flame" – and eventually they reach a boundary, "a massive wall of rock bisected", which "cut the world right through".

Readers will of course recognise biblical parallels here: the wandering in the wilderness, the pillar of fire. They might also recognise the presence of those other books and that other place that haunts so much of Grossman's work – the world described in the stories of Sholem Aleichem, the world of the eastern European shtetl, a place alive with cobblers and matchmakers, and alive also with the presence of the dead, and the living dead. "Under a street lamp," writes Grossman, "that glows with a yellowish light stands an elderly man writing in chalk on the wall of a house. A white halo of hair hovers around his head, his walrus moustache is silver, and my soul alights when I realise it is my teacher, my maths teacher from elementary school, a likable man who suffered a tragedy years ago, I cannot recall what, and disappeared. I thought he was dead, yet here he is …"

If there is a lack of specificity in Grossman's description of the town and the walkers, and if the story perhaps sometimes becomes lost and confusing, then it is because the landscape and its inhabitants are really shadows, creatures of an interior world, whose journey and whose quest are within.

Falling Out of Time is short, and clearly a deeply personal book, but its importance and impact ought not to be underestimated. The great miracle of writing, Grossman concluded in his Freedom to Write lecture, is that "from the moment we take pen in hand or put fingers to keyboard, we have already ceased to be a victim at the mercy of all that enslaved and restricted us before we began writing. We write. How fortunate we are: the world does not close in on us. The world does not grow smaller."

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion