Air quality in London on April 3, 2014 fell to a level where it became hard to see normally-visible skyscrapers. Conditions hit a 9/10 risk ranking thanks to a combination of pollution and dust blown in from the Sahara desert. Tackling such pollution could immediately improve people’s health, stresses New York University’s George Thurston. Image copyright David Holt, used via Flickr Creative Commons license.

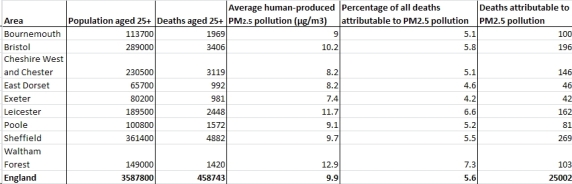

Sometimes when I blow my nose and – inevitably – look into my handkerchief, I see that my snot is black. It doesn’t happen when I’m at home, in the small English city of Exeter, only when I’m in London. It’s a clear sign of the extra pollution I’m inhaling when I’m in the capital – one backed up by data published last week by Public Health England. Its striking report says that in 2010 73 deaths per thousand in the London borough of Waltham Forest, where my girlfriend’s sister lives, could be put down to grimy air. For Exeter, the figure was just 42 per 1000. Across the whole of England, pollution killed 25,002 people in 2010, or 56 of every 1000 deaths nationwide.

But wherever you live, air pollution will become even more important as the climate changes, while fighting this scourge could also help the world bring global warming under control. “There’s more than enough rationale for controlling emissions based on the health effects and the benefits that we get as a society from getting off of fossil fuels,” New York University’s George Thurston told me. “Those are the benefits that are going to accrue to the people who do the clean-up – locally and immediately, not fifty years from now.”

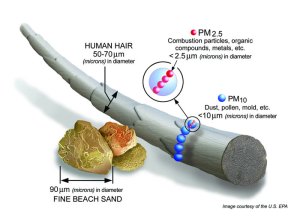

Public Health England is trying to draw attention to ‘particulate matter’, or dust, less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter, too small to see with our naked eye. You won’t find this ‘PM2.5’ pollution listed as people’s cause of death – it’s likely to be down as a heart attack or lung cancer. George has run huge studies in the US to help work out exactly how much such dust worsens people’s health. One study for the American Cancer Society followed 1.2 million men and women originally enrolled in 1982. Another, started in 1995, tracked over 500,000 US retirees over the following decade. And he was also a part of a worldwide project that last year showed ‘global particulate matter pollution is a major avoidable risk to the health of humankind’.

It does particularly matter

Technically dust, dirt, soot, and smoke, are large or dark enough to be seen with the naked eye. “Inhalable coarse particles,” have diameters larger than 2.5 micrometres and smaller than 10 micrometres and “fine particles”, also known as PM2.5 pollution, have diameters that are 2.5 micrometres and smaller. Image credit: US Environmental Protection Agency

By closely scrutinising people’s lifestyles, where they lived and when they died, George and his colleagues could tease out the consequences of higher pollution levels. “Most of the deaths have cardiovascular causes,” he said. “Heart disease is already a big problem, and if you do something that increases the risk of that, then it adds up to a lot of deaths.”

Seemingly tiny amounts of fine particle muck, measured in micrograms – millionths of a gram – per cubic metre (µg/m3), can therefore have far more serious effects than just colouring snot. George and his colleagues had found that just a 10 µg/m3 increase in fine particle concentrations was linked to a one-tenth to one-fifth increase in risk of death from cardiovascular disease. Bodies like Public Health England can then use such figures to work out what proportion of all deaths were down to air pollution, and in turn how many people it’s killed.

Meanwhile, although they’re not greenhouse gases black, sooty carbon particles often produced at the same time as PM2.5 pollution warm the atmosphere by intercepting and absorbing sunlight. Black carbon has been called ‘the second most important individual climate-warming agent after CO2’. Burning fossil fuels – for example in power stations or vehicles – is a major source of both CO2 and black carbon. Bringing black carbon into consideration therefore makes reducing our reliance on fossil fuels even more desirable.

By using climate models, researchers at Environment Canada showed in 2012 that a future scenario that brings climate change under control by 2100 would also cut PM2.5 levels. Looking across North America, they found climate change alone would increase PM2.5 pollution by more than 0.2 µg/m3 between the two periods 1997-2006 and 2041-2050. Over much of the eastern US and the Hudson Bay in northern Canada, levels grew by 0.5-1 µg/m3. But the relatively modest emission cuts that they modelled would generally reduce PM2.5 by as much as 10 µg/m3 in some areas.

Modelling studies show how getting off fossil fuels could benefit PM2.5 pollution in North America. (a) shows 1997-2006 ten year average summer PM2.5 levels. (b) Shows the difference from (a) in PM2.5 by 2041-2050 from climate change alone, with red areas showing the largest increases. (c) Shows the difference from (a) in PM2.5 by 2041-2050 with modest emissions cuts. (d) Is the same chart as (b) redrawn with the scale used in (c) for comparison purposes. The fact there are blue areas, which mean PM2.5 levels are reduced in the later period, in (c) but not (d) shows that steps to bring climate change under control will also help pollution levels. The red areas you see in (b) are missing from (d) because the map is redrawn with a wider scale, needed to fit in the PM2.5 reductions gained by cutting emissions. Copyright Copernicus Publishing/European Geoscience Union used via Flickr Creative Commons license, see Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions reference below.

Getting the message through the smog

New York University’s George Thurston feels the immediate health benefits of getting off fossil fuels are just as powerful as the long-term climate impacts. Image credit: New York University

As well as showing the benefits of cleaning up our fuel supplies, that paper also hints at how climate change would likely worsen the health impact of air pollution. This effect comes because the climate helps determine how pollutants move through and are removed from the air. Likewise, another group of scientists at Stanford University, California, found in 2012 that one likely impact of a warmer world would be more days with stagnant air conditions.

The air would be more stagnant in some regions thanks to decreases in wind and rainfall, which then lets pollution linger, the Stanford team found. In a scenario where CO2 emissions peak around 2050, the eastern US was particularly sensitive to this problem, as were Mediterranean Europe and eastern China. By the end of the 21st century, they project, stagnant days in industrial regions will be an eighth to a quarter more common than at the end of the 20th century.

With even bodies like Public Health England trying to draw attention to air pollution, you’d think the chances were good that something would be done. But here in the UK, we scarcely talked about it until pollution hit the highest level used by the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) earlier this month. Then, dust clouds blown in from the Sahara desert were partly blamed for the air getting a 10/10 ranking for dirtiness, with DEFRA advising the sick and people experiencing sore eyes or throats to limit what they do outside. But that level’s been achieved five times a year on average for the past five years, with DEFRA making hardly any effort to get its warnings out.

Such failures are part of the reason George highlights that we need greater action to get fossil fuel particles out of our noses, lungs, and our health overall. He adds that doctors and climate researchers should combine in pushing our governments to recognise the multiple benefits reducing emissions would provide. “I don’t think the politicians are really going to do this without scientists and physicians stepping forward and saying we need to clean up the air for health reasons as well as climate change reasons,” he said. He also stresses that the health benefits of any cuts would be effectively immediate. “Lowering fossil fuel combustion, changing over our energy use, would cause a reduction in the number of people dying every year,” George emphasises.

Selected air quality and related mortality figures extracted from Public Health England’s report ‘Estimating Local Mortality Burdens associated with Particulate Air Pollution’

Journal references:

Pope, C. (2003). Cardiovascular Mortality and Long-Term Exposure to Particulate Air Pollution: Epidemiological Evidence of General Pathophysiological Pathways of Disease Circulation, 109 (1), 71-77 DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000108927.80044.7F

Smith, K., Jerrett, M., Anderson, H., Burnett, R., Stone, V., Derwent, R., Atkinson, R., Cohen, A., Shonkoff, S., Krewski, D., Pope, C., Thun, M., & Thurston, G. (2009). Public health benefits of strategies to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions: health implications of short-lived greenhouse pollutants The Lancet, 374 (9707), 2091-2103 DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61716-5

Horton, D., Harshvardhan, ., & Diffenbaugh, N. (2012). Response of air stagnation frequency to anthropogenically enhanced radiative forcing Environmental Research Letters, 7 (4) DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/7/4/044034

Kelly, J., Makar, P., & Plummer, D. (2012). Projections of mid-century summer air-quality for North America: effects of changes in climate and precursor emissions Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Discussions, 12 (2), 3875-3940 DOI: 10.5194/acpd-12-3875-2012

Thurston, G. (2013). Mitigation policy: Health co-benefits Nature Climate Change, 3 (10), 863-864 DOI: 10.1038/nclimate2013

Rice, M., Thurston, G., Balmes, J., & Pinkerton, K. (2014). Climate Change. A Global Threat to Cardiopulmonary Health American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 189 (5), 512-519 DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201310-1924PP

April 19, 2014 at 3:23 pm

Reblogged this on JustinBowenZa.

April 19, 2014 at 6:54 pm

People in Spain regularly have dust blowing into their houses. It would be interesting to compare cardiovascular disease rates in Spain, Portugal and other Mediterranean countries exposed to Saharan dust.

April 19, 2014 at 7:39 pm

The IPCC wrote about this cobenefit of tackling climate change quite a bit in WGII and it is a significant benefit. It needs more publicity so I’m glad you’ve written this. The health effects of pollution are a huge burden on global health.

Click to access WGIIAR5-Chap11_FGDall.pdf

April 19, 2014 at 11:15 pm

Absolutely! I’m certain the Chinese could well relate.

April 22, 2014 at 2:04 pm

[…] 2014/04/19: SimpleC: Dump fossil fuels for the health of our hearts […]

April 22, 2014 at 7:18 pm

[…] 2014/04/19: SimpleC: Dump fossil fuels for the health of our hearts […]

May 30, 2014 at 9:19 am

http://wattsupwiththat.com/2014/05/29/then-they-came-for-the-airplanes/ is also relevant here. People don’t talk about airliners much (not enough, in my opinion)

May 30, 2014 at 11:24 am

I agree, it’s not mentioned often enough. At the recent IPCC conference they said that transport will be one of the hardest sectors to decarbonise. Did you see the low carbon airplane option for the Longitude challenge?

Thanks for the link – interesting to use how Watts uses the study as a prompt for outrage.

May 30, 2014 at 11:37 am

No, please point me to the low carbon aeroplane – that would be interesting.

May 30, 2014 at 11:40 am

This is the link to the overview of the idea, you can click through to the deeper explanation of the flight challenge:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-27425224

May 30, 2014 at 8:37 pm

That is going to be tough. 2% of all emissions ! I wonder what is it is for cars, buses, lorries, trains, ships ?