Few in China knew the truth two years ago, when then-president Hu Jintao travelled to a naval base in the northeastern city of Dalian to mark a signal moment in the rise of Chinese power: the unveiling of the Liaoning, the first aircraft carrier commissioned by Beijing's navy.

More than a decade earlier, a penniless Ukraine government had sold the aging carrier at a fire-sale price to a Chinese company pledging to turn it into a floating casino. When it was towed out of the port of Nikolayevsk in 2001, everyone thought it was headed for the gambling haven of Macau. In fact, it was destined to become not only the symbol of China's ambition to dominate the seas around it, but to project power thousands of miles from its coasts.

Sitting in Moscow, Russian president Vladimir Putin knew the truth, and it had to chafe: Here was yet another tangible symbol of the decline of what had been the second-most powerful navy on earth—that of the former Soviet Union. He was determined to reverse that trend. And so he has—most recently by seizing what was left of the Ukrainian navy in Sevastopol.

China and Russia—the United States's two biggest strategic rivals—have made it plain they plan to challenge America's monopoly of sea power. In Beijing, spending on the navy (known as the PLAN—the People's Liberation Army's Navy) has surged.

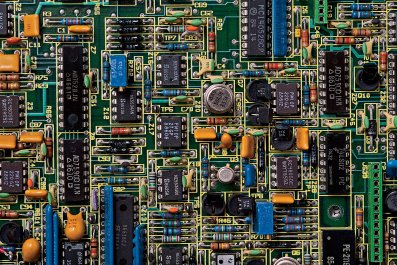

Beijing has been banging out three submarines a year—it now has 28 active nuclear submarines and 51 submarines overall. PLAN has commissioned 80 surface ships since 2000, compared with about 48 vessels commissioned in the 1990s. By 2020, Beijing plans to have three aircraft carrier–led battle groups—meaning that two aircraft carriers are under production.

China's ambitions go far beyond this increase in naval hardware. Chinese leaders now routinely refer to "blue national soil"—the oceans that extend off its coast line—which they demarcate far beyond the 200 nautical miles that are its "exclusive economic zone" under the U.N.'s Law of the Sea Treaty. Beijing has even issued a map—known as the "nine dash line"—which purports to show China's waters lapping against the Philippines and Vietnam. "China," write Toshi Yoshihara and James Holmes, of the U.S. Naval War College, "is on the brink of commanding the seas with Chinese characteristics."

To date, those "Chinese characteristics" mainly consist of an increased capacity to drive the U.S. out of Beijing's waters. The strategy aims to create a buffer zone to prevent an enemy's approach. The lynchpin is the submarine fleet, but the plan also includes fast-attack vessels equipped with anti-ship missiles, which distresses U.S. navy war planners.

According to Christian Le Miere, an analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, China has deployed between 65 and 85 of these vessels so far, "suggesting that the strategy behind their use is to deploy rapidly, perhaps in small flotillas, to harry larger vessels with difficult to intercept missiles."

China's naval buildup reflects several geopolitical goals. As Robert Kaplan writes in Asia's Cauldron: The South China Sea and the End of a Stable Pacific, it gives Beijing what defense analyst Li Mingjiang calls a "strategic hinterland" that stretches over 1,000 miles—one that would act as a "restraining factor" for the U.S. Navy's Seventh Fleet in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

Another motivation is energy: The South China Sea is replete with oil and gas reserves, for which Beijing has a voracious appetite. It is now the world's largest importer of hydrocarbons. The fundamental tensions that Beijing's maritime ambitions bring are now on full display within Vietnam's exclusive economic zone, where the Chinese National Offshore Oil Company is drilling for oil from a rig it just deployed there—over Hanoi's furious but fruitless objections.

"What's the difference between an oil rig and a naval base or an aircraft carrier? Very little, politically, in the eyes of China," says Dean Cheng, defense analyst at Washington's Heritage Foundation. Beijing is extending reach, daring Vietnam (or anyone else) to do something about it, confident in its ability to project sufficient naval force to defend what it sees as its interests.

To date, in extending its economic interest in the South and East China seas, China hasn't always relied on its navy per se, as the current clash with Hanoi illustrates. In 2012, Chinese fishing vessels travelled to the Scarborough Shoal, a disputed set of tiny outcrops 124 miles west of Subic Bay. They were caught fishing illegally for giant clams and sharks and were detained by the Philippine coast guard. Beijing reacted furiously—sending its own ships to defend the fishermen—and dispatching warships to linger menacingly on the horizon.

A tense, 10-week standoff ensued, until Manila blinked. Beijing today occupies the Scarborough Shoal and Chinese officials have boasted about using the Scarborough Model as a way of intimidating regional neighbors.

Indeed, China has dispatched fishing vessels near the disputed Senkaku Islands (known to the Chinese as the Diaoyu Islands), the flashpoint of Beijing's dangerous standoff with Japan—the only power in east Asia with a military that can stand up to China's. As Ely Ratner, deputy director of Asia Pacific Security Program at the Center for a New American Security in Washington has written, these disputes are Beijing flexing its muscles, thanks in large measure to an increasingly capable and sophisticated PLAN.

Russia's naval ambitions are linked closely to China's rise: After all, Beijing's relentless economic growth sent global prices for almost all the commodities Russia has been naturally endowed with soaring—from oil to gas to timber to iron ore. That has stuffed the coffers of Russian state-owned companies and enabled Moscow to again begin funding its military, after nearly two decades of post-Cold War decline.

Putin has pledged $700 billion to boost Russia's military over the next two decades—much of it to go to naval hardware. The Kremlin's shopping list includes half a dozen Admiral Grigorovich–class frigates and as many aircraft carriers; eight Yasen-class attack submarines; and a new generation of ballistic missile submarines designed to carry out nuclear attacks on the U.S. These Borei-class boats carry 16 nuclear-tipped Bulava missiles, each with 10 warheads that can "thwart evolving Western ballistic-missile defense shields," according to U.S. Navy Reserve Lieutenant Commander Tom Spahn. He calls Russia's newest boats and missiles "alarmingly sophisticated."

Russia's navy has become an important symbol of a resurgent Russia. Putin's popularity plummeted early in his reign with the loss of the Kursk, an Oscar-2 class attack sub that went down with all 118 hands after a faulty torpedo burned up in its tube in 2000.

Russia has 68,000 miles of coastline—the third longest, after Canada and the U.S.—and over 80 percent of the supplies to Russia's Far East go by ship, mostly via the Indian Ocean. A third of Russia's nuclear arsenal—more than 600 warheads—is carried on the navy's submarines.

And, of course, it makes for great television. "Putin loves the navy.… There's nothing more impressive than a battleship or submarine with its crew paraded in dress uniforms," says Semyon Vlasov, a former consultant to the Duma's Defense Committee.

Every great Russian ruler has made their mark on the high seas. "Peter the Great announced that Russia was a European power by creating a navy on the Baltic," says St. Petersburg–based historian Andrei Grinev. "Catherine the Great showed Russia was a world power by defeating the Ottoman [Turkish] navy at Cesme in 1770, and colonizing Alaska."

Putin is acutely aware of this historical resonance. He has revived the Russian naval station at Tartus in Syria, the only Russian military facility outside the former Soviet Union. Established in 1971, the "Material-Technical Support Point" is, in reality, a tiny sliver of land less than half a mile long equipped with two 100-yard-long floating piers, neither big enough to accommodate even the smallest of Russia's frigates.

In January 2013, Russia evacuated its last personnel from Tartus, leaving Syrian contractors in charge of a single Amur-class floating workshop. "Tartus exists mostly so that Russian officials can talk about it," says one Western diplomat who visited the port in 2010. A planned visit in 2009 by Russia's only aircraft carrier, the Admiral Kuznetsov, was cancelled after seven of her eight turbines failed and a fire broke out on board. The carrier has only managed four deployments since she was commissioned in 1991. (U.S. naval captains nickname her "Tug-bait.")

Still, Russian defense minister Sergei Shoigu has great plans for Tartus, and in February called for a network of Russian naval bases in Vietnam, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, the Seychelles and Singapore. "Naturally, Russia is interested in having resupply and maintenance bases for our navy in several states," confirmed Russian deputy foreign minister Anatoly Antonov in March. "We are engaged in talks on the issue."

"Russia," Admiral Eduard Baltin, former commander of Russia's Black Sea Fleet, toldRussian Reporter, "is returning to the stage in its power and international relations, which it, regrettably, lost at the end of last century. No one loves the weak."

Putin is also deploying his navy to push Russia's economic interests. Technology is making the rich mineral resources under the Arctic seabed accessible for the first time—and Moscow insists that swathes of the undersea territory are geologically contiguous to Northern Russia, giving it the right of possession under international law.

The question is being adjudicated by the U.N.—but in the meantime the Northern Fleet Admiral Andrei Korablev has announced that Russia will reopen a military base in the Novosibirsk Islands abandoned 20 years ago and reinforce it with 10 warships and four nuclear-powered icebreakers. The navy will also install military infrastructure on almost all the islands and archipelagos of the Arctic Ocean to create what Korablev calls a "unified system of monitoring air, surface and subsurface conditions."

His fleet will also be sent to patrol Franz Josef Land, Severnaya Zemlya, the Novosibirsk archipelago and Wrangel Island to back up the Kremlin's claim to the world's largest untapped oil reserves—control over which is now contested by Russia, the U.S., Denmark, Norway, Canada and, more recently, China.

Of the two, it is China's naval build up that, for now, most concentrates minds in the Pentagon. Beijing's far-reaching claims amount "to an expansionist strategy with profound implications for U.S. power and regional security," says Ratner. At the end of the Cold War, the U.S. had 15 carrier battle groups, compared to 11 today. How much longer Washington's spending on sea power can be limited depends in part on what both Beijing and Moscow do.

And now, the signals are going in one direction. Last December, a PLAN warship attached to the Liaoning's battle group peeled off and sailed straight at the U.S.S. Cowpens, a guided missile cruiser shadowing the aircraft carrier, forcing it into a dangerous game of chicken.

Washington remains the dominant naval power globally. But the gap is closing—quickly.