This is Part 3 of my series, “How to Design a Worker Placement Game.” Most of this piece is applicable to any type of game design, but it draws specific examples from worker placement games. Regardless of the type of game your working on, you may find this useful.

I’ve been very pleased with the response to this series. I’ve also appreciated the additions that accomplished designers have made with their comments. Feel free to tell your own stories and add your own thoughts in the comments section below. We all benefit. The League wants to hear from you!

If you’re new here, check out the first two installments of this series:

How to Design a Worker Placement Game Part 1

How to Design a Worker Placement Game Part 2

How to Design a Worker Placement Game Part 4 – Manhattan Project: Energy Empire

You can find a Chinese translation of these posts at boardgame-record.blogspot.tw

Part 1 and Part 2

REFINING YOUR GAME

The final stage in designing your worker placement game is the refine step. During this stage you take all of your game concepts and drafts and build cohesive prototypes that are good enough to stand on their own. You engage in extensive playtesting and gathering of feedback. You continue to tinker and trim the elements of your game, and like a barrel of good Scotch, you let it age.

HOW, EXACTLY DO YOU REFINE YOUR GAME AND GET IT JUST RIGHT?

THE ANSWER IS, YOU DON’T.

…not alone anyway. The refine step is one that should not be carried out behind closed doors. Good games are like good legislation, they should be crafted in the public eye, with public input, and in the full light of day.

The League of Gamemakers strongly believes in the collaborative spirit of gamemaking. After all, we formed a League!

Refining a game is a vast topic that could fill volumes, but like a good game, this piece will be focused, limited to the following three sections:

- TRIMMING AND TINKERING

- SHARING THE LOAD

- DESIGNER SPOTLIGHT: BUMPING BEARDS AND ORANGE TROBILS

TRIMMING AND TINKERING

Much of a game designer’s work is in the nitty gritty details. We can spend all our waking hours on the precise effects of a card, the number of spaces on a track, or the exchange value of a certain resource. In these matters, a designer must make countless decisions, each one potentially affecting all other aspects of the game. Whenever possible, you should look for the simplest solution that does the job, and the solution that will be most easily conveyed in the rules.

It’s when you actually sit down to write the rules where you’ll really get a feel for the “teachability” of your game. Things that might have made perfect sense during rough play tests can become incredibly contrived when you actually try to explain them in writing. Consequently, waiting until a late stage to write your rules can pose problems. As much as your game “works” during playtests with friends, you still need the printed rules to precisely convey all aspects of the game. I recommend writing down some of your rules as you go along, and to use player reference cards with abbreviated rules.

Playtesting is a massive topic, so I’ll only touch on it briefly here. Ultimately, you want your game to be purchased and enjoyed by many people. You’re never going to please everyone with your game, but you still want to have enough demand for your game that it will sell. Consequently, you want a lot of testing to see how real people interact with your game, and a lot of face time with your potential audience so that you can get a feel for the marketability of your game. Did they like playing it? Did they want to play again? Did they ask when it will be going on Kickstarter or available in stores? Or, are you scaring people away from playtesting your game?

When you run a play test and find a glaring problem that can be fixed, do so right away, rather than charging on. If you continue your play test, that problem may overshadow other aspects of your game. Allow yourself permission to tinker on the fly.

DON’T GO TOO FAR

Don’t go too far. Friends who’ve playtested my games know that I can be guilty of this. Sometimes, I’ll take a criticism, an inspiration, or a suggestion, and I’ll run with it- which is great. But soon I’ve completely overhauled my game to make room for this new concept, and I’ve introduced a whole new set of untested “accommodations.” It’s true that once in a while a big change is what a game really needs, but usually tinkering should be just that – some new allow wheels, a shiny coat of paint, and some chrome. Be cautious of additions or changes that require many other changes in order to make them work. Consider these new ideas, test them, but keep your old stuff close by. Check out this great piece by Kevin Nunn on his blog, Mechanisms and Mechanics on “Using Playtester Feedback.”

Often during the refine step, you’ll need to undergo some trimming. Designers often come up with more ideas than they know what to do with. You might even have twelve expansions in the works for a game you haven’t finished. In an era where three hour games dominate the ratings, it may sound strange to say this, but most games have some fat to trim. Sometimes the fat is an overly complicated mechanism. Sometimes it’s simply the number of different cards or tokens. Sometimes multiple parts of the game really serve the same purpose. Wherever you can make your game efficient, do so. Lighten your load, put a little air in the tires and lean out the fuel mixture.

How long does all this tinkering take? Months, maybe years, and maybe it will never be complete. It’s different for every game, and different for every designer. One thing is clear, you’ll make more progress on your game by getting more people involved, and letting go of trying to solve every problem yourself. Be patient, and be aware that it can take quite some time to publish a game. According to Jeff Cornelius, a boardgame is art, and you can’t rush art.

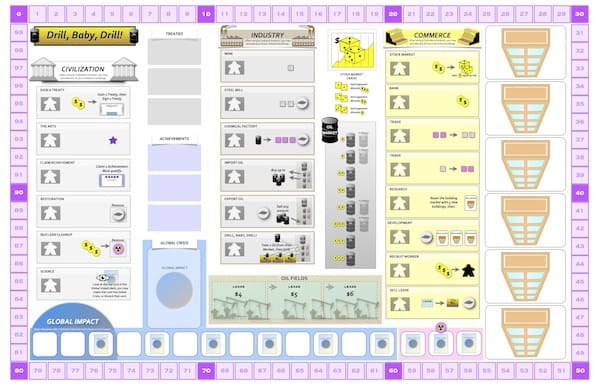

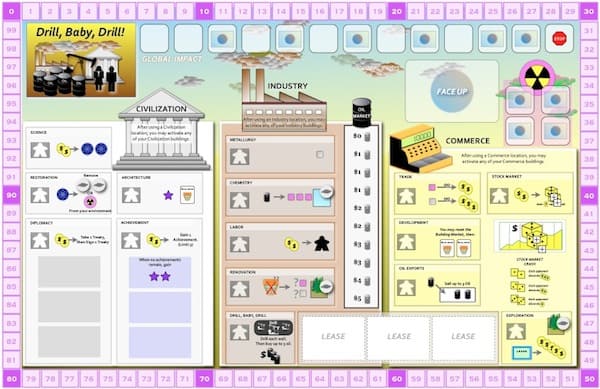

Here’s a trimming and refining example from a current project of mine, Drill, Baby, Drill. Essentially, the only major difference between these two boards is that there are fewer spaces to place workers, yet most of the same options are still available.

DRILL, BABY, DRILL BOARD: VERSION 3

DRILL, BABY, DRILL BOARD: VERSION 4

SHARING THE LOAD

It may sound like something straight out of a scifi novel, but whether you like it or not, you’re part of a collective. Those ingenious ideas you have for your worker placement game are heavily borrowed from your experiences with other games and your interactions with other people. Likewise the entire purpose of your game is to bring people together to share an experience. The simple fact is that your design is not even a game until people play it.

As collectives go, the design community is pretty awesome. Far from being of one mind, we come from a variety of different backgrounds, we hold down all manner of day jobs, and we each bring something unique to the field. Trust us. Join us. We won’t steal your game.

There are many ways to become involved in the community and to get help on your games. In your local area, find out if there is a design group. Look for connections on social media: Facebook, twitter, Boardgamegeek, The Game Designer’s Forum, and Meetup.com.

JOIN THE GUILD

One of the best online communities, with daily conversations on a wide range of design topics is the Facebook Card and Board Game Designer’s Guild, with over 3500 members:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/GameDesignersGuild/

GO TO EVENTS

Attend conventions near and far. If you can, attend a Protospiel event: special workshops where designers, play testers, and publishers gather together to play test and refine games. Many games have been picked up by publishers at Unpub and/or Protospiel events. This Geeklist compiled by Peter Vaughan lists some of them: Published Protospiels

Some League members will be attending this Unpub/Protospiel in California this week: www.boardgamebuilders.com. Look for posts about this event and League members experiences there.

DESIGNER SPOTLIGHT: BUMPING BEARDS AND ORANGE TROBILS

Two of my colleagues are currently hard at work refining worker placement games. Each is an interesting and innovative game, and the two games are quite different from each other.

TREASURE MOUNTAIN

Treasure Mountain is a fantasy-themed worker placement game designed by Dan George in which players control competing clans of dwarves. I asked Dan to talk a bit about his playtesting process after playing Treasure Mountain. I was truly amazed by the high level of quality he put into his prototypes, and his innovative bumping mechanics.

CAN YOU DESCRIBE YOUR INITIAL PROTOTYPES?

“I start my prototyping process by making one copy. I use Corel Draw to create the initial design and construct it by hand. The graphics are just basic and contain lots of white space so I can write notes directly on the game components.”

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN A GAME IS READY FOR BLIND PLAYTESTING?

“It’s a feeling I get when I have played it within my own gaming groups after 20 or more plays. The game feels “interesting” and “fun”. I know that’s not very specific. I can tell you that I design at least four games a year. I would say that only one in 20 get to a point where I feel I want to blind play test them. Most of my designs don’t pass muster but each is a learning opportunity. I know it’s a cliché, but I learn more from my failures than my successes.”

WHAT HAS BEEN THE BIGGEST SURPRISE FOR YOU FROM FEEDBACK ON TREASURE MOUNTAIN?

“I am surprised by the absolute variety of play-test feedback in this game more than my others. Some of my play tests groups loved one aspect of the game while the other did not care for the same aspect. As a designer, I know that good playtesters have strong opinions (most gamers do). A designer can’t take each of these opinions to heart or you will find yourself literally torn apart. I feel the feedback needs to be sifted for truly “broken” mechanics and all options weighed against each other before making hasty game redesigns.”

HOW MUCH DO YOU EXPECT TO CHANGE THE GAME IN RESPONSE TO FEEDBACK?

“It’s too early at this point. I tend to play test a long time. There are some obvious things like the color of one of the gems (it is black in the play test copies because I had no blue gem) or replacing the wood with beer.”

WHAT WOULD YOU ESTIMATE THE COST OF PRODUCING YOUR PROTOTYPES?

“Well, this is a question I hate to even think about. Treasure Mountain is a very component-heavy game, but I had a lot of the parts already laying around in my garage. I made four blind playtest copies and each took me about 2 hours of labor to make at a component cost around $40.” (That cost does not include shipping)

WHERE DID YOU GET ALL OF YOUR COMPONENTS FOR YOUR PROTOTYPES?

“I have four HUGE bins of game parts that I have collected over the last 20 years. However, sometimes I do buy more.”

THE FOLLOWING ARE SITES RECOMMENDED BY DAN GEORGE FOR BUYING GAME PARTS:

- https://www.boardgamedesign.com/

- https://www.printplaygames.com/

- https://www.boardsandbits.com/index.php

- https://www.thegamecrafter.com/

- https://www.admagic.com/

- https://www.meeplesource.com/

- https://maydaygames.com/game-pieces/

- https://www.gameparts.net/

- https://www.rolcogames.com/

ASKING FOR TROBILS

Asking for Trobils is coming to Kickstarter on May 21st. It is being published by Kraken Games, and is designed by Christian Strain and Erin McDonald. It is a worker-placement boardgame in which players are trying their best to rid the star system of Trobils. The game is one color: orange .

Christian describes his playtesting process as follows:

“We playtest in 3 stages. The first stage is just the two designers playing the game 3 or 4 times a day trying out new methods and ways to play to see if we can break the game, and we do, often. That’s the point of the first stage. This is where the game’s metal is initially purified.

The second stage is playtesting with friends and family. This is to test the fun factor. We ask people to play with the widest ranges of experience and likes and dislikes of that particular game. If I’m making a worker placement game and my cousin hates worker placement games, I want him there. Get people who you know will hate it, love it, and pick it to death for you. This is where the game gets forged into the shape most people will see.

Stage 3, my favorite, is blind testing. Go to your local game shops and ask if you can host blind play testing there. They’ll get players who you’ve never met and know nothing about the game to come and play the game. Just hand them the rule book. Don’t teach. At this point they should be experiencing the game just like a regular customer who’s just opened the box. Do this as many times as the store will tolerate you. Don’t allow people who have played to stick around and play twice though. They skew the results for the new table. This is where your game is finally sharpened and crafted to the best game it can be.

When do you know you’re ready? Put your money where your mouth is. In our last blind test for Asking for Trobils, we’re going to offer some prizes to anyone who finds misspellings or errors that need to be corrected. After a few blind testings with no one getting prizes, you’re good to go!”

ASKING FOR TROBILS WILL BE LAUNCHING ON KICKSTARTER MAY 21ST!

I hope you found some of the information and resources useful. I look forward to continuing the dialog on these topics. Feel free to post comments below, and spread the word about the League of Gamemakers!

And now, Part 4 is complete, revealing how this all turned into Manhattan Project: Energy Empire