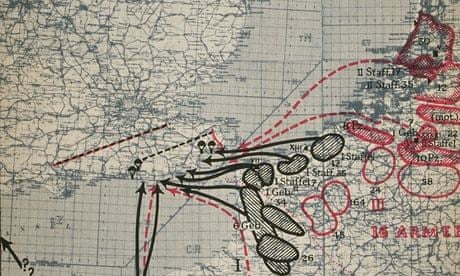

The Nazi spies arrived on the shores of Britain under the cover of night, by parachute, by rowing boat and by rubber dinghy. In their suitcases each carried a morse code transmitter, a map of the UK, a handgun and some invisible ink. Their mission: to pave the way for an invasion.

But the spies chosen for the mission had neither convincing fluency in English nor basic knowledge of British customs. One spy was arrested after trying to order a pint of cider at 10am, unaware that during wartime landlords weren't allowed to serve alcohol before lunchtime. Another pair were stopped while cycling through Scotland on the wrong side of the road: once the police discovered German sausages and Nivea hand cream in their luggage, their cover was blown.

Of the 12 spies who landed in Britain as part of Operation Lena in September 1940, most were arrested without having come closing to fulfilling their mission, and "because of their own stupidity", as British official records put it. Why Germany sent such inept agents on one of the most important missions of the second world war has remained an enduring mystery.

A book published in Germany this summer comes up with a new explanation. In Operation Sealion: Resistance inside the Secret Service, the historian Monika Siedentopf argues that the botched spying mission was not the result of German incompetence, but a deliberate act of sabotage by a cadre of intelligence officials opposed to Hitler's plans.

Siedentopf first became interested in the story of Operation Sealion – the German plan to invade Britain – while researching a book on the role of female spies during the war. For many other missions, German spies had been meticulously well-prepared, she noticed, so why not in 1940?

Her research led her to a circle of people around Herbert Wichmann, the officer in charge of the Hamburg intelligence unit, one of Nazi Germany's biggest secret service posts.

Wichmann had close ties not only to Wilhelm Canaris, the spy chief once dubbed the "Hamlet of conservative resistance" by Hugh Trevor-Roper, but also to the Stauffenberg group which planned to assassinate Hitler in July 1944.

At the end of the war, Wichmann was given a key role in rebuilding Hamburg's shipping industry, upon express orders of the British. MI5 described him and his circle as "good Germans, but bad Nazis".

After six years of research in the National Archives and using Wichmann's own writing, Siedentopf deduced that the spy chief had deliberately sent agents on Operation Lena who had neither particularly good knowledge of the country nor the language.

Instead, his preference appears to have been for individuals with low levels of intelligence but resounding enthusiasm for National Socialism, many of them petty criminals and members of far-right organisations in the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark.

Wichmann's motives, Siedentopf told the Guardian, were mixed. He feared not only that Operation Sealion was badly planned and would come at a considerable human and material cost to Germany, but also that an attack on England would escalate the conflict into a proper world war – but preventing that was an objective that even its most inept spies could achieve.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion