I’m an epileptic.

It’s not how I define myself, but I am writing about epilepsy, so I think pointing out the fact that I am speaking from experience is acceptable.

I may not define myself by my epilepsy but it’s a big part of my life. It affects my life on a daily basis. Because of the epilepsy I can’t drive, can’t pull all-nighters or get up really early just in case I have a seizure. It’s frustrating at times, though I will gladly milk the not getting up early thing when I can, eg bin day.

But whereas I’ve grown up with it, having been diagnosed when I was 17, most people I’ve met don’t understand it. You mention the fact that you’re epileptic to some people and they look at you like they’re a robot you’ve just asked to explain the concept of love; they adopt a sort of “DOES NOT COMPUTE!” expression.

They often don’t know what to say, or do, or even what epilepsy is and often spend the rest of the conversation searching their data banks for information on what to do if I have a seizure, like “Do I … put a spoon in his mouth?”

For the record: no, you don’t. If putting a spoon in an epileptics mouth helped, then we would be prescribed a constant supply of Fruit Corners.

So let me put you at ease. No one expects you to know that much about epilepsy (unless you’re responsible for treating it). There are many different types, with many different causes. Not everyone has seizures and often those who do, when given the correct meds, can live pretty much fit-free lives.

I have tonic-clonic epilepsy. It used to be called grand mal epilepsy which was a much better name for it, I mean Big Bad Epilepsy? It sounds brilliant. It’s the type of epilepsy that causes full-blown seizures – falling over, convulsing, chewing of the tongue and the like. Some are worse than others, but they always make me feel like I’ve had a full work-out. To someone watching, it must be deeply disturbing; to me it’s just annoying, though I have damaged furniture more often than I’ve damaged myself.

How a seizure works is a bit weird. As I understand it, it’s like your brain is a computer of sorts. It runs on electricity that follows the path of the circuitry. Occasionally a short circuit will send that electricity down the wrong pathway, which causes your brain to activate everything before shutting down and rebooting. However, this computer is connected to everything you own, so when the blue screen of doom hits it, everything stops what it was doing and then starts again. It doesn’t matter that you were half way through printing a 100-page document, it’s going to start printing test pages, playing cartoons and sending pointless emails to easily confused family members.

Unlike your computer, though, you can’t take it apart to find out what’s wrong with it.

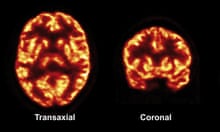

Brain mapping technology has come on leaps and bounds since I first had wires glued to my head and a light flashed at me. You can scan your brain, have an MRI or an EEG and get a really good picture of the landscape of your brain.

The problem is, these machines are best at showing you if there’s something obvious wrong with your brain. Any damaged bits, any hot spots, the machines have a good chance of picking it up. Often though, and in my case as I have generalised epilepsy, there is no obvious cause, so there’s no obvious cure/treatment. You can’t pinpoint one part of the brain and aim your treatment there (not that it’s that simple anyway). If the brain is functioning all right most of the time, doctors are loathe to poke about with if they can avoid it, and rightly so.

So they give you medicine. The problem with a medicine that is aimed at a nonspecific area of the brain is that it is going to affect all of it. It has to. So there are dozens of potential side effects, from hair growth to hair loss, liver damage to seizures (the irony is not lost on me). So you have to weigh up whether the benefit of not having seizures is worth these side effects.

So is it worth it? Having a seizure is a weird feeling. It begins with a sensation in the mind. A glitch in my brain. I can feel that I’m going to have a seizure, but I have no control of my body. The fall seems like a physical stutter, a very disconcerting sensation, almost like watching myself fall, mentally trying to stop myself.

Then I’m unconscious, unaware of what my body is doing. What it is doing is tensing and relaxing, flexing and flailing, gripping and releasing. It usually doesn’t last long, and then I’ll wake up in a mental fog and carry on with what I was up to. I’ll have conversations, take out the bins, have breakfast (sometimes for the second time in close succession) but I won’t remember a thing. My brain has activated all of my muscles, made them work hard for a couple of minutes and now both my body and brain are exhausted. So I sleep for as long as needed.

But I have found unforeseen bonuses. That shake-up of the mind, that brainstorm (yes, I’m co-opting the term) often gives me strange ideas, vivid images, words connected bizarrely – as if someone had emptied the toy box of my mind and joined together bits of mental Lego and a Rubik’s cube and produced something that no one had seen before. As a writer and comedian, it has given me some bizarre nuggets of comedy such as doing stand-up as a seagull, dancing wearing a grotesquely massive Ainsley Harriot mask and surreal gags about everyday things like eggs. I even got to the finals of ITV comedy competition Show Me the Funny, mostly due to material created in the aftermath of seizures.

Having controlled my epilepsy myself for years, without medication and with reasonable success, I recently made the decision to start taking medication again. And it worked. More or less. I’ve had a couple of seizure in the past couple of years, but only under extreme pressure.

But the big ideas have also stopped. The weird and wonderful connections that made my work different have seemingly dried up. It could be writers block or it could be coincidence, but I suspect that it has something to with the meds.

The question is, am I willing to risk stability for wild ideas? The ability to get up early for bleary-eyed gibberish? And the truth is – I don’t know.

Dan Mitchell is a comedian and actor, and is on Twitter as @specileptic

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion