Being Happy With Sugar

Popular media are full of claims that sugar is toxic. And there’s intense disagreement about recommendations to replace table sugar and high-fructose corn syrup with “natural” sweeteners like agave nectar or fruit juice.

What to make of it all?

“Over the past few months, I’ve become increasingly concerned about a sweetener that I’ve recommended on my show in the past,” Mehmet Oz lamented in an apology earlier this year. Oz, the practicing cardiac surgeon and professor at Columbia University who hosts an eponymous daytime-television extravaganza, is given to emphatic food recommendations. Either run and buy something, or throw it away. Throw it as far from you as possible. “After careful consideration of the available research, today I’m asking you to eliminate agave from your kitchen and your diet.”

That’s a stark difference from 2011, when fans of Oz’s show listed their “all-time favorite tips” from Doctor Oz, and number one was “Agave Nectar as a Sugar Substitute.” Number one. Agave flooded “natural” food aisles. By 2012, agave nectar sales were projected to double within the decade, as they had the decade prior. America’s Doctor was at the helm.

“What I like is agave,” Oz said in one of his first-ever appearances on Oprah in 2004.

“Agave? I don’t know what that is, agave.” Winfrey looked to the audience with a puzzled brow, to comedic effect.

“Agave is a natural sugar, but it’s really, really powerful. It’s very sweet to the palate,” Oz explained, recommending it specifically as a substitute for high-fructose corn syrup. “It’s actually a natural product, it’s really, really sweet. You just put a little bit in your tea or whatever you’re eating, so you don’t get many calories.”

Agave has about 60 calories per tablespoon, compared to 48 calories for the same amount of table sugar, though less agave is required to deliver the same sweetness.

In a subsequent 2009 appearance on Oprah, Oz made a strikingly similar recommendation in responding to a question about stevia.

That same year, Oprah’s “Ask Dr. Oz” segment spun off to become The Dr. Oz Show, where agave came up again and again. “The next time that you’re craving something sweet,” Oz said, “try using agave nectar as a natural sugar substitute.”

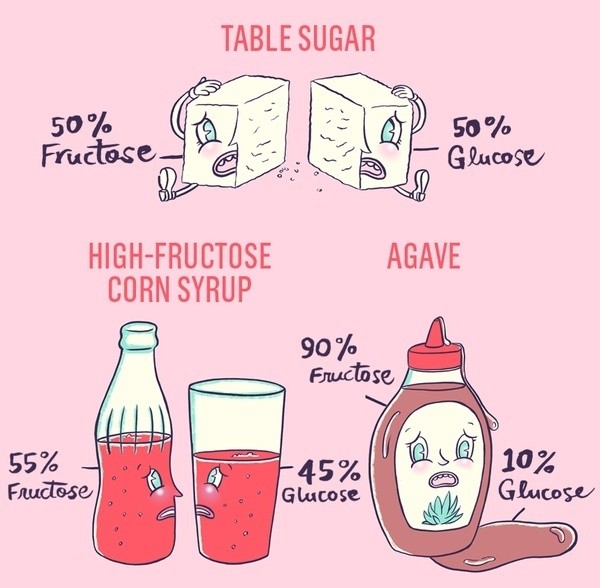

In his recent retraction of these endorsements, Oz offered the explanation, “It turns out that although agave doesn’t contain a lot of glucose, it contains more fructose than any other common sweetener, including high-fructose corn syrup.” Fructose is the sweetest naturally-occurring carbohydrate, so that’s why agave syrup is sweeter-per-volume than competitors.

By that time, other health-media giants had also withdrawn from agave-lauding. “I've stopped using agave myself and no longer recommend it as a healthy sweetener,” Dr. Andrew Weil wrote in a 2012 blog post. His explanation was strikingly similar to Oz’s: “As it turns out, agave has a higher fructose content than any other common sweetener, more even than high fructose corn syrup.”

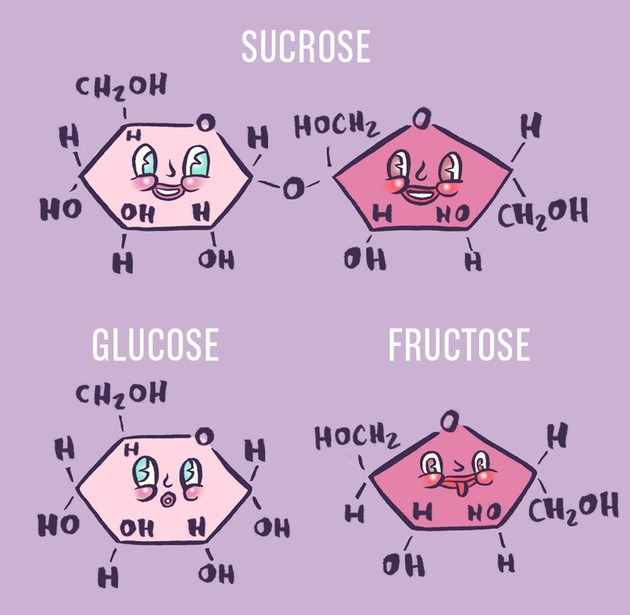

Of course, the fructose content of agave nectar, or syrup, is an empiric piece of data that has long been available. What hasn’t been widely available is a clear understanding of what fructose actually does to our bodies. Doctors like Oz and Weil championed agave not just because it seemed to be “natural,” but because it has a low glycemic index, meaning it increases your blood-glucose levels more slowly than other types of sugars. The glycemic index, introduced by Dr. David Jenkins at the University of Toronto in the 1980s, categorizes carbohydrates based on their impact on our blood-glucose levels and insulin release after eating a particular carb, with less impact long understood to be a virtue. But to put all your stock in glycemic index is to deify fructose. Agave contains between 70 and 90 percent fructose by weight, and fructose has the lowest glycemic index of any sugar.

High-fructose corn syrup, which has been used commercially since the late 1960s, can be misleading as a name in that the fructose content is only high relative to regular old corn syrup. High-fructose corn syrup has fructose content similar to that of table sugar (sucrose)—55 and 50 percent, respectively—so their glycemic indices are higher than that of agave. Since the “natural” food craze took hold, agave has been marketed as an alternative to the laboratory evils of HFCS. Pretty much without fail there’s a picture of a plant or Earth on the label, and you can buy yoga mats in an agave palette.

Agave is a plant, but the syrup we make from it is like any sweetener, a mixture of fructose and glucose. After growing for around seven years, a mature blue agave plant sprouts a pyramidal flower that dangles up to twenty feet in the air, where it can be pollinated by bats. The succulent is a relative of yucca, and it was used by people as far back as the Aztec empire. William H. Prescott described agave’s many uses in 1843’s The History and Conquest of Mexico, “The agave, in short, was meat, drink, clothing, and writing materials for the Aztec!” Today in factories the blue agave plant is crushed and its aguamiel (honey water) collected. The natural plant fiber inulin is processed into fructose and glucose using thermal hydrolysis, which involves quickly heating the juice to a high temperature and then cooling it. (In the case of agave that is sold as “raw,” the hydrolysis happens at a lower temperature for a much longer time.) The process yields a product amber in color, with a consistency like maple syrup and flavor like honey, only more delicate. Despite the processing it undergoes, the plant origins made agave popular as a sweetener in “natural” and “wholesome” nutrition bars, sugary drinks, and other foods.

What turned the media against agave was the recent demonization of fructose.

In a 2010 article headlined, “Shocking! This ‘Tequila’ Sweetener Agave Is Far Worse Than High-Fructose Corn Syrup”—which has been viewed online more than half a million times—the quixotic Dr. Joseph Mercola, proprietor of a “natural health” website that claims to reach millions of readers daily, wrote, “In case you haven't noticed, we have an epidemic of obesity in the U.S. and it wasn't until recently that my eyes opened up to the primary cause: fructose.”

“Excessive fructose consumption deranges liver function and promotes obesity,” Weil declared en blog in his recantation. “The less fructose you consume, the better.”

“Initially, we thought moderate amounts of fructose weren’t unhealthy, but now we know better,” Oz corroborated earlier this year.

On an even larger platform, Dr. Sanjay Gupta said in a grave voice on 60 Minutes, “New research, coming out of some of America’s most respected institutions, is starting to find that sugar, the way many people are eating it today, is a toxin.” Gupta shot straight into the heart of the fructose story to talk with Dr. Robert Lustig, a professor of pediatrics at UCSF whose viral anti-fructose 2009 lecture is credited with the popularization of the idea. Lustig used the terms “toxin” and “poison” 13 times in the 90-minute lecture, which now has 4.5 million views on YouTube.

“Do you ever worry that just sounds a little bit, over the top?” Gupta asked Lustig, of the claim that fructose is toxic.

“Sure, all the time. But it’s the truth.”

He added later, “I think one of the reasons evolutionarily is because there's no food stuff on the planet that has fructose that is poisonous to you. It is all good. So when you taste something that's sweet, it's an evolutionary Darwinian signal this is a safe food.”

Gupta: “We were born this way?”

Lustig: “We were born this way.”

The concern is that when a person consumes too much fructose, their liver gets overwhelmed and converts some of the fructose into fat that ends up in their blood as small dense LDL that lodges in blood vessels, causing atherosclerosis and, subsequently, heart attacks.

Lustig is a gifted talker, and he has his points down. He has called sugar “the Professor Moriarty” of the obesity epidemic, before upping the metaphor and calling fructose “the Darth Vader of this sordid tale, beckoning you to the dark side.” It’s this narrative that emerged as the backbone of the documentary Fed Up, which premiered at Sundance in January and is now in widespread release. Produced and narrated by Katie Couric, the film takes us through interviews with more than 20 nutrition experts, basically a who’s who of New York Times Magazine nutrition articles in the last decade—Marion Nestle, Michael Pollan, Gary Taubes, Michael Moss, Michele Simon, David Ludwig—and others who constitute what Times food columnist Mark Bittman calls “the professional sane eating brigade.”

In building a case that “everything we’ve been told about food and exercise for the past 30 years is dead wrong,” the film’s anti-fructose message came through as Lustig was quoted again and again. The basis of the “We’ve been lied to” conspiracy appeal of Fed Up is what Lustig calls an ongoing, ruinous myth: A calorie is a calorie. As stated on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s site, “A calorie is a calorie, regardless of its source.” That has long been the basic tenet of weight loss. The American Beverage Association, which represents the soda industry, echoes that dismissiveness on its site: “Quite simply, overweight and obesity are a result of an imbalance between calories consumed and calories burned.”

“It’s not about the calories,” Lustig said in his famous lecture, and reiterates in Fed Up. “It has nothing to do with the calories.” The film says that is the myth we’ve been fed. Lustig says fructose “is a poison by itself.”

Many in the sane eating brigade have also written that a calorie is not a calorie, not just because some calories are empty and some are accompanied by valuable antioxidants or vitamins, but because sugars influence satiety, metabolic rate, brain chemistry, and hormone release in different ways than other sugars and other macronutrients. (Marion Nestle is not among them; her recent Why Calories Count argues that a calorie is indeed a calorie.) When researchers have given animals enough pure fructose, their livers convert it to the saturated fatty acid palmitate, which increases LDL cholesterol levels in their blood, increasing their risk for heart attacks. Fat also accumulates in the liver itself, which results (over time) in insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome. Colorado State University biochemist Michael Pagliassotti observed these changes in as little as a week when animals were fed huge amounts of fructose or sucrose. When he stopped giving the animals sugar, their fatty livers and insulin resistance went away.

Kimber Stanhope, a nutritional biologist at the University of California Davis, has produced similarly compelling research that showed subjects who consumed pure fructose as 25 percent of their calorie intake had higher levels of triglycerides in their blood than people who consumed the same amount in pure glucose. That’s more fructose than almost any person would even be able to eat, though Stanhope says around 10 percent of Americans do get at least a quarter of their daily calories from added sugars of one kind or another, which is unsettling. Stanhope said recently that the abundance of epidemiological evidence suggests sugar could be a cause of heart disease. “Do we need to wait for these results [of studies showing a causal relationship] before we revise the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and start educating the public accordingly?”

Probably, because if there is a problem in all of this, it’s that speaking definitively before definitiveness is due can spread more confusion. Some find the “sugar is the enemy” message to be an oversimplification that makes the same mistake as the “fat is the enemy” message it is replacing: Advocating nutrient-focused eating instead of a holistic approach to eating nutritious foods, and less of it.

In "Is Sugar Toxic?," a popular 2011 feature story in The New York Times Magazine, brigade member Gary Taubes offered the provocation, “If what happens in laboratory rodents also happens in humans, and if we are eating enough sugar to make it happen, then we are in trouble.” Reasonable people disagree on the magnitude of those ifs.

“To say that fructose is toxic is a total misconception of the nature of the molecule,” Fred Brouns, a professor of Health Food Innovation at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, recently told me. “If you have too much oxygen, it is toxic. If you get too much water, you have water intoxication. That doesn’t mean we say oxygen is toxic.”

In March, Brouns published a challenge in the journal Nutrition Research Review titled “Misconceptions About Fructose-Containing Sugars and Their Role in the Obesity Epidemic.” It took the fructose story to task, noting the integral role that popular media plays in science:

“Since the recent publications of Lustig and co-workers, in which it was suggested that fructose is toxic and should be ‘treated as alcohol,’ the daily news all over the world highlighted fructose in sugar-sweetened beverages as a potential poison. ... The metabolic effects of fructose presented in ordinary human diets remain poorly investigated and highly controversial. ... One may rather aim at reducing the consumption of energy-dense foods.”

Brouns makes a call for skepticism, not absolution. “There have been studies that show fructose, when consumed in isolation, can be toxic,” he told me, “but we never consume fructose in isolation. It is eaten with glucose.”

Stanhope conceded the same thing when we spoke. Her study also showed that people who consumed a quarter of their daily calorie requirement as high-fructose corn syrup in a laboratory setting (55 percent fructose, 45 percent glucose) did have elevations in triglyceride and cholesterol levels similar to those who ate as much in pure fructose. As for looking at something closer to what people regularly consume, Stanhope has completed forthcoming research (currently under review by the Journal of the American Medical Association) that looks at what happens to our livers at lower levels of consumption. She declined to foreshadow the findings.

Even Barry Popkin, who was investigating fructose long before Lustig, recommends caution. Popkin, a distinguished professor of nutrition at the University of North Carolina, co-authored a widely-read academic article in 2004 titled “Consumption of High-Fructose Corn Syrup in Beverages May Play a Role in the Epidemic of Obesity.” That paper was followed by many popular articles that cited it, and a lot of research down this road. But he didn’t mean for it to lead to all-out fructose terror.

All that Popkin really wrote in the original article was that metabolism of fructose, unlike glucose, favors production of fat in our livers. That leads to a fatty liver, a condition that affected at least 70 million Americans at the time, and affects many more now. Fatty liver is linked to insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease.

Popkin also noted that eating fructose doesn’t induce a chemical signal that tells our brains we’re full. “Unlike glucose, fructose does not stimulate insulin secretion or enhance leptin production,” Popkin explained in 2004. “Because insulin and leptin act as key afferent signals in the regulation of food intake and body weight (to control appetite), this suggests that dietary fructose may contribute to increased energy intake and weight gain.”

A recent review of many large meta-analysis studies did find that calories from sugar are all the same in terms of obesity outcomes. Be it bread, pasta, or pixie sticks, the researchers found that at least when it comes to carbs and weight, a calorie is a calorie. “Intake of sugars is a determinant of body weight in free living people consuming ad libitum diets,” authors led by Jim Mann, professor of human nutrition and medicine at the University of Otago in New Zealand, write, referring to the fact that people advised to eat less sugar all seem to lose an average of two pounds. The study’s conclusion corroborated the traditional wisdom about calories and weight loss: “Change in body fatness that occurs with modifying intake of sugars results from an alteration in energy balance,” not from metabolic consequence of particular sugars. They found that replacing sugars with other carbohydrates “did not result in any change in body weight.” Roughly translated, for body weight, a calorie of carbs is a calorie of carbs. Though, this didn’t take into account fatty liver or heart disease that Lustig notes can well be present in the skinniest of people.

But even Popkin says the evidence isn’t really clear that high-fructose sweeteners are worse than others. “Our article was really a call for research,” Popkin told me recently, “and it’s led to years of intensive research on the effects of fructose in our diets.”

The amount of sugar Americans consumed before the late twentieth century was trivial compared to what we eat today, Popkin noted. “We’re in a whole new world of sugar consumption. It’s not just beverages; it’s in all the foods. And we don’t really know what that means to our health. We know that we face an epidemic of things like fatty liver disease. Not just obesity, not just diabetes, but many other problems that could potentially be related to all the sugar. We think from some studies that fructose could be responsible, but we don’t have slam-dunk evidence on any of it.”

Popkin cautioned me that arguments downplaying the dangers of sugar may be swayed by soda-industry lobbying. Suspicion of industry influence intrude on many discussions of what should be basic biochemical science. Popkin assured me, unprompted, that he advocates taxing sugar-sweetened beverages (and fruit juices alike) and is “still seen as a scholar not bought off by industry.”*

When Brouns makes comments, as he did when we spoke, like “fructose is not the enemy; the main cause of obesity is overall lifestyle and eating too much of everything,” he is marked as a potential industry shill, perpetuating the same myth that the government purportedly force-fed us for years. In fact, Brouns did work with Cargill until 2008, but he maintains no ties.

Skepticism about the safety of processed food lends an air of nobility to the anti-HFCS crowd, and gives a health halo to “natural” sugars. In “Five Reasons High-Fructose Corn Syrup Will Kill You” [29,000 Facebook likes], Dr. Mark Hyman, chairman of the Institute for Functional Medicine, recently noted, “The average American increased their consumption of HFCS (mostly from sugar sweetened drinks and processed food) from zero to over 60 pounds per person per year. During that time period, obesity rates have more than tripled and diabetes incidence has increased more than seven fold. Not perhaps the only cause, but a fact that cannot be ignored.” Hyman likens the corn industry calling its product corn sugar to calling tobacco in cigarettes a natural herbal medicine. (The Corn Refiners Association applied to officially rebrand high-fructose corn syrup "corn sugar" in 2010, but the request was denied by the FDA in 2012, to the applause of natural-food advocates.)

“I don't think there's any doubt that Americans consume much too much fructose, an average of 55 grams per day (compared to about 15 grams 100 years ago, mostly from fruits and vegetables),” Weil wrote in his definitive agave takedown on DrWeil.com. “The biggest problem is cheap HFCS, ubiquitous in processed food.”

“The rates of shark attacks in Australia also increase with the rates of ice eating,” Brouns told me. “Because when it is hot out, more people go swimming. There is also a correlation between grey hair and osteoporosis.”

High-fructose corn syrup can’t be a particular driver of the obesity epidemic in the U.S., Brouns says, “because obesity has grown just as quickly in countries that barely use HFCS. It is a misconception.” For one example, Coca-Cola in Mexico famously contains sucrose in place of high-fructose corn syrup. “Natural” sodas at places like Whole Foods advertise that they, too, have sucrose or fruit-juice concentrate instead of HFCS. But Mexico has recently been jockeying with the United States for claim to the most obese country in the world.

Others argue that HFCS is worse than table sugar because the fructose in table sugar is “actually attached to other sugars and molecules and needs to be broken down before it is absorbed, which limits the damage it causes,” as Mercola wrote in his popular anti-agave article. “In HFCS, it is a free fructose molecule, just as the glucose. Because these sugars are in their free forms their absorption is radically increased and you actually absorb far more of them than had they been in their natural joined state.”

Popkin told me that is not a well-substantiated claim. “Clinical trials haven’t shown that mattered one iota. People might make those arguments. But there’s no clinical trial showing a difference.”

Popkin’s real concern at the moment is the use of fruit-juice concentrate as a purportedly healthy natural sweetener. “Starting about six or seven years ago, we started seeing a huge spike in the amount of fruit-juice concentrate that was added to foods. Is that because people think it’s quote-unquote natural?”

In Spike Jonze’s film Her, the proselytizing neighbor-character Charles reminded Joaquin Phoenix’s character Theodore Twombly, “By juicing the fruits, you lose all the fibers, and that’s what your body wants. That’s the important part. Otherwise, it’s just all sugar, Theodore.”

Not everyone who juices will spiral into technophilic romantic turpitude, but from an overall health standpoint, it can’t hurt your odds to stop. Though it definitely does take eating a lot of fresh fruit to consume the amount of sugar that’s in fruit juice. “Nobody has shown that we have any reason to worry about the fructose that naturally occurs in fruit,” Stanhope told me. It’s true that the fiber that comes along with the sugar in fruit slows its sugars’ digestion to a “natural” rate. It’s extremely difficult to eat enough fruit for the sugar to become nutritionally consequential. Dr. David Katz, director of Yale’s Prevention Research Center, wrote in a 2012 U.S. News and World Report column, “You find me the person who can blame obesity or diabetes on an excess of carrots or apples, and I will give up my day job and become a hula dancer!” He is still director of Yale’s Prevention Research Center.

One day in her lab, Stanhope actually had her staff try to eat enough fruit to get 25 percent of their daily calories from sugar (the quantity she has shown to be harmful). She said four of the seven people were unable to complete the task. “It was more fruit than they could bear to eat.”

As Stanhope puts it, “Nature provided fructose in quite dilute packages compared to what we’ve done with our food.” Even raw sugar cane is only about ten percent sucrose. So, chomp on sugar-cane stalks all you like. “We have concentrated that fructose in ways I suspect nature never meant us to eat it.”

That line of reasoning that merits an important distinction. Agave nectar and fruit-juice concentrate are not “natural” in the sense that whole fruit is natural, but they defend themselves the same way. The recently proposed FDA nutrition labels include the suggestion that the nutrition information panel add in a line that notes how many “added sugars” are used in a product. Many food companies, especially those that operate in the organic and “natural” space, are lobbying that fruit-juice concentrate should not be included as an added sugar on labels. Popkin says fruit juices are at least as dangerous as any other kind of sweetener. To even consider not including it as an added sugar on labels concerns Popkin deeply.

Brouns, similarly, says that industry can help by cutting down on added sugars, but “blaming added sugar as the main cause of obesity is totally wrong. I think that is misleading the public. Pretty soon everybody will be focusing on sugars in the same way that, years ago, everybody was focusing on fat.”

The glycemic index concept told us that foods high on the scale (high in glucose or anything that quickly breaks down into glucose) cause our blood sugar to spike and fall, to ill effect. It was this same glycemic-index that led Oz to recommend agave nectar to Oprah. The glycemic index has proven to be a very rough indicator of a food’s quality—for example, carrots have a high glycemic index, and lard has a glycemic index of zero. Isolated metrics can justify one way of eating or another, to make claims on packages and in commercials. Trends in nutrient-based eating come and go.

Yesterday agave was in, and today it’s out. “Natural” has little meaning for health outside of produce aisles. Eliminating sugars from a diet can’t constitute playing it safe, in that it means getting calories elsewhere—just as the advice to cut out fat in the 1980s is blamed for making people increase their consumption of sugar. Too much fat is bad, too much protein is bad, and too much starch is bad. Everything is good, and everything is bad. Even looking back, the basic tenets of the original 1980 USDA nutrition guidelines really do seem to hold up: “Eat a variety of foods; avoid too much fat, saturated fat, and cholesterol; eat foods with adequate starch and fiber; avoid too much sugar; avoid too much sodium.” And, of course, “Food alone cannot make you healthy.”

In Fed Up, Katie Couric refers to the 1992 food pyramid, which was all carbs at the bottom, but also to the popular practice of calorie balancing, which she says is based in misunderstanding. “What if the solutions weren’t really solutions at all? What if they were making things worse? What if our whole approach to this whole epidemic has been dead wrong?”

Rhetorical questions are the currency of extraordinary implications in documentaries. What if our whole approach to this epidemic has been part of an ongoing investigation into understanding the complex nature of human metabolism and nutrition, and it's all building on itself, and there’s some validity to most of it?

*An earlier version of this article indicated that Barry Popkin opposes a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. He favors a tax—based on sugar content, not on volume of the beverage.