The following is excerpted from Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations with Today's Top Comedy Writers by Mike Sacks.

Will Ferrell doesn’t mince words when describing Adam McKay, his longtime friend and comedy collaborator. “He’s kind of a dangerous individual,” Ferrell says. “He’s extremely funny; there’s no doubt about it. But he’s dangerous. I wouldn’t stay in a room with him, one on one, for any longer than I had to. There’s a criminal tendency there. We have a great working relationship because I don’t ask him much about his past. He just frightens me.” Ferrell is joking, obviously. But there was a time, years before McKay found Hollywood success directing and co-writing films such as Talladega Nights: The Ballad of Ricky Bobby (2006) and The Other Guys (2010), when he might very well have been the most dangerous man in comedy.

In June of 1995, McKay was making history at Chicago’s legendary Second City, in a sketch revue called Piñata Full of Bees. It would prove to be one of the most seminal and groundbreaking productions in the theater’s history. Set apart by its aggressive approach to political and social satire, Piñata tackled such seemingly unfunny subjects as wealth corruption, racism, and the massacre of Native Americans. McKay is often given sole credit for masterminding its strong political point of view.

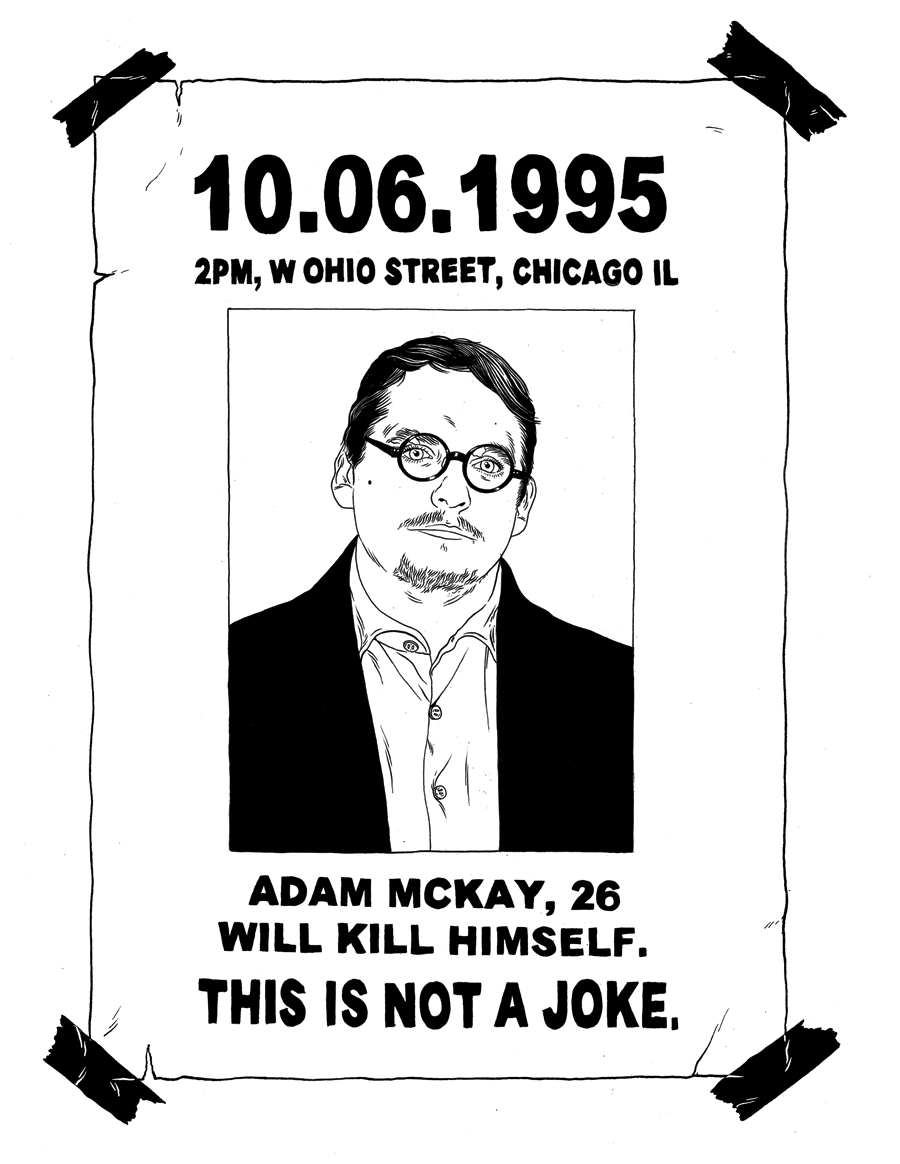

Is it true that in the mid-nineties, while you were in the Chicago improv scene, you publicly improvised your own suicide?

Yes, that happened. I had an actor’s photo, a horrible eight-by-ten glossy, that I inserted into a poster. And the poster read: “On such-and-such-a-date, Adam McKay, 26, will kill himself. This is not a joke.” I put up the poster everywhere, and on the assigned location and date, there was a huge turnout. I went to the roof of a five-story building and yelled down to the crowd. We had a CPR dummy dressed exactly as I was dressed, and we threw it off the roof. Someone else was playing the character of the Grim Reaper, and he collected the dummy and hauled it away. Meanwhile, I ran downstairs and “came to life,” and we all ended up back in the theater where we finished the show.

Good luck not getting arrested in New York with that stunt.

[Laughs] It was the type of thing you could only get away with in Chicago. Anywhere else, I’d have immediately been hauled away. But it was also the perfect time. Nowadays with the Internet, people would just go, “Oh, it’s performance art” or “It’s a flash mob” or whatever. But it wasn’t commonplace back then. There weren’t as many hidden camera shows. Nowadays, this stuff is so common, you can’t truly surprise people.

There was just this freedom. There was just a freedom to try to get away with whatever you felt you could get away with. Del Close encouraged that.

So Del would actually encourage improv that took place on the streets, in front of unsuspecting people?

Oh my God, he loved it! You know, when I faked my own suicide, Del was on the street literally screaming, “Jump! Jump!” He had always thought our improv group was pretty good, but once we started doing these kind of stunts—we once even staged a fake street revolution, with audience members hitting the streets with lit torches and fake guns—an extra fondness came in. That’s when Del really started knowing our names and caring about what we were doing.

Do you think you ever went too far with these stunts?

I might have done things differently if I could do them over again. There was one time when Scott Adsit [the actor who later played Pete Hornberger on 30 Rock] and I and the rest of our group were performing in front of an audience. This was when Bill Clinton was president. Scott came out and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, I have some terrible news. President Clinton has just been assassinated.” Scott’s a really good actor and he played it very real. The whole crowd completely believed it. We then wheeled out a television to watch the most up-to-date news coverage. We turned it on and NFL bloopers came on—we had already inserted a VHS tape. One of us yelled, “Wait, don’t change it!” The whole cast came out and hunkered down and just started laughing at these football bloopers. The people in the audience slowly began to file out, dazed. That was the end of our show.

And you know, that’s the kind of thing you do when you’re twenty-five or twenty-six. Now that I’m a forty-four-year-old, I think, You can’t do that. What happens if someone starts sobbing? What happens if . . . . There are too many what ifs. But at twenty-six, you’re not quite that compassionate. I’ll now bump into members of the improv group and say, “Can you believe we did that?” But that was part of the process. We were pushing things as far as they could go. And the only reason I accept it now is that there was real satire there: entertainment and silly pop culture trumping real information. But we probably should have popped it. There probably should have been some reveal at the end. Something to clue the audience in to the fact that what they had just seen was staged.

Illustration By Louise Pomeroy

This interview is excerpted with permission.

Purchase the book below: