Autism

Autistic vs. Psychotic Spectrums: Overlapping or Opposite?

Evidence of both opposite and overlapping factors emerges from a new study.

Posted May 2, 2016

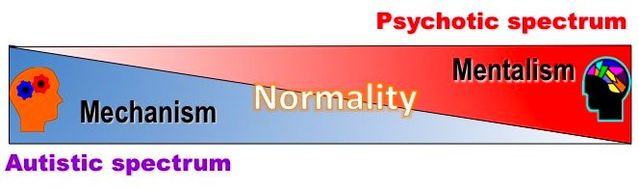

The idea that, rather than being discreet entities, mental illnesses may lie on a spectrum of some kind is gradually gaining ground, but the question of exactly how they relate remains. Conventional views have some autistic and psychotic symptoms overlapping but, according to the diametric model of mental illness illustrated below, autism and psychosis are opposites.

Up to now, a major frustration has been that, because it represents a completely new and original paradigm, the diametric model has not been applied in research in the way in which conventional ideas inevitably have been. But now, a dozen or so years after I first published them online (2002), Guillaume Sierro, Jerome Rossier and Christine Mohr have explicitly set out to test these “independent notions.”

According to the diametric model, both autistic and psychotic disorders lie on common but anti-correlated continuums of mentalism and mechanism illustrated above. In other words, more of one normally means less of the other. As these authors put it:

Mentalism refers to a cognitive style characterized by enhanced abilities in perspective taking, mentalizing (i.e. theory of mind, mindreading), and sensitivity to gaze (allowing efficient interpersonal interactions). Mechanism refers to a cognitive style characterized by enhanced abilities in perception, memory and attention to detail (allowing efficient interaction with the physical world).

Sierro, Rossier, and Mohr add that the autism spectrum “would be characterized by diminished mentalizing (hypo-mentalism) and increased interactions with the physical world (hyper-mechanism). What they term the "schizophrenia"—but I would call the psychotic—spectrum, on the other hand, “would be characterized by increased positive symptoms (hyper-mentalism) and diminished interactions with the physical world (hypo-mechanism).” (Authors’ emphasis.)

The diagram above is purely an illustration of this and of what is in reality a much more subtle situation, and one where mechanism basically equates to the brain and mentalism to the mind. (A table in a recent post lists diametric contrasts between the two modes in detail, and those between the symptoms of autistic and psychotic spectrum disorders are listed in another.) Cognitively speaking, the picture above represents diametric savantism: in other words, only a very few remarkable people are found at the extremes with such skewed cognitive profiles. But they do exist. Kim Peek, featured in the previous post, quite closely approximated to the hyper-mechanistic, hypo-mentalistic, autistic savant extreme. Indeed, my point in that post was that a machine mind might easily be mistaken for a human one if it presented itself as such a savant. By contrast, what I would call psychotic savants such as Bruno Bettelheim or Trofim Lysenko, described in earlier posts, approximate to the other, mentalistic extreme.

However, as these examples of diametrically opposite savantism suggest, mentalistic deficits are much more socially stigmatizing than mechanistic ones, simply because mentalism is primarily a social adaptation. Mechanistic deficits, although now seen as part of the so-called psychotic endophenotype, are much more easily concealed, and nothing like as socially- or personally-disabling as mentalistic ones (even if they can do enormous harm, as Bettelheim for example did with his hyper-mentalistic, "refrigerator mother" theory of autism or Lysenko did on an even greater scale with his mentalization of biology in the USSR). So in practice the situation is not as simple as this diagram suggests, and as a result many people diagnosed as autistic have not only mentalistic, but mechanistic deficits too. Furthermore, these cases of comprehensive retardation vastly outnumber the few savants, and true genius—outstanding gifts in both directions—is even more rare.

Clearly, and unlike any existing model, the diametric one offers a simple explanation of the entire range of cognitive configurations from retardation to genius, autism to psychosis, and everything in between: notably normality. But models are one thing; proof is another!

By way of testing the model, Sierro, Rossier, and Mohr used data from 921 French-speaking Swiss undergraduates (of whom 665 were female) to validate the French Autism Spectrum Questionnaire (AQ), identifying an optimal factor structure. Additionally, they assessed relationships between this AQ structure and schizotypic—or high-functioning psychotic—personality traits.

Results from correlational and principal component analyses replicated previous research these authors cite in suggesting both overlapping and opposing relationships: in other words, both contradicting and confirming the diametric model. However, as the authors point out, the picture with regard to overlap between autistic and psychotic spectrums is complicated, and some measures they used have their limitations: for example, they comment that autistic and schizotypic profiles “may not be distinguishable using short instruments representing a broader personality.”

Again, they point out that overlap “may reflect a genuine shared phenotype (e.g. a bias for unusual information/interests), or confounded phenotypes:” for example “apparently similar interest in unusual features resulting from opposite hyper-mechanistic or hyper-mentalistic cognitive styles (e.g. respectively, a mathematical versus numerological interest in numbers” (authors’ emphasis). Indeed, this is something that strikingly illustrates Isaac Newton’s genius: he was both a supreme mathematician (and co-discoverer of calculus along with Leibnitz) and a brilliant Biblical numerologist (who, among other things, thought that he had discovered that the Second Coming would occur in 2060!).

The authors report that they replicated “the overlapping relationships between ‘positive’ and ‘negative’ traits” in both the autistic and psychotic spectrums, along with “opposing relationships between ‘positive’ schizotypic and autistic traits…” The positive traits the authors have in mind here include delusions, hallucinations, compulsions, and pathological elaborations or exaggerations of normal behaviour. According to the diametric model, all of these are products of hyper-mentalism in one way or another. So-called “negative” traits, as the term suggests, describe a lack of emotional response, apathy, withdrawal, avoidance of social contact, and depression. And also according to the diametric model, these are often products of hypo-mentalism and of specific mentalistic deficits, such as an inability to socialize appropriately or to empathize with others.

However, most of these negative traits can also develop as secondary symptoms of psychosis for the simple reason that both excessive and deficient mentalizing can result in a person becoming socially isolated, depressed, avoidant, and apathetic. Unfortunately, most of the measures used by researchers today cannot distinguish between autistic as opposed to psychotic negative secondary symptoms, so the finding that there is a seeming overlap in this respect is hardly surprising. Indeed, in my personal view, such negative symptoms are like fever: not an illness in itself, but symptomatic of many different disorders.

Not surprisingly then, Sierro, Rossier, and Mohr comment that “the psychometric measurement of the diametrical model remains a challenging task.” By way of improving things they make a number of suggestions including adding personality items accounting for hyper-mentalism (e.g. mentalizing-related positive schizotypic traits along with manic, impulsive and attention-seeking traits, and paranormal beliefs). They also recommend including items accounting for hypo- and hyper-mechanistic cognition, adding that it is likely that future studies will be able to distinguish between autistic and psychotic spectrum disorders on a mechanistic continuum as well as on a mentalistic one—just as the diametric model has always proposed.

(With thanks to Christine Mohr for providing me with an advance copy of this paper.)