Rapid urbanisation in many parts of the developing world is putting an increasing strain on the ability of cities to deliver critical services such as water and sanitation. More than half of the world’s population – 54% – live in urban areas and some 700 million of them do not use an improved sanitation facility, where human waste is separated from human contact.

But even where there are such facilities, this does not necessarily translate into environmentally safe practices. More than two billion people in urban areas use toilets connected to septic tanks or latrine pits that are not safely emptied or that discharge raw sewage into open drains or surface waters. With another 2.5 billion people expected to live in cities by 2050, authorities urgently need to keep up with the growing urban population, ensure equitable access to improved sanitation, and safeguard the appropriate and environmentally-safe management of human waste.

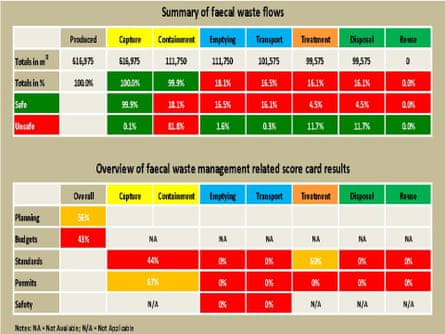

Believe it or not, mapping the journey of faecal waste is an important part of the solution. IRC’s new sanitation assessment tool offers a simple representation of the volumes of sludge safely (and unsafely) dealt with at each stage of the sanitation chain, allowing city planners to determine where the biggest losses are and where to focus their (often limited) budgets.

Although tools to assess faecal sludge management (FSM) do already exist, they are either not able to include qualitative information or the scorecards they provide do not give adequate explanations for a bad score, nor do they provide actual volumes, which makes it difficult to translate the results into action. IRC’s tool, however, analyses the availability and enforcement of policy and legislation, and the presence of and adherence to health and safety through specific scorecards.

The tool works by conducting interviews with relevant city officials and collecting information about the current sanitation situation, which is supplemented by data from existing plans and reports. Teams of sanitation professionals and local support staff will then visit selected neighbourhoods to check the various facilities and validate the data already obtained. Teams will also visit existing wastewater or faecal sludge treatment plants to verify whether the waste actually gets there.

After all this data is collected and validated, it is entered into various spreadsheets that make up IRC’s tool. The tool then processes the calculated volumes and generates score cards, which are reviewed and used for reporting.

The tool was tested in the city of Mataram, the capital of West Nusa Tenggara province in Lombok, central Indonesia. The city has an estimated population of 450,000 people, but within two weeks enough data was collected to give the local government a comprehensive insight into the current sanitation situation. While city authorities were worried about citizens who did not have access to any type of toilet facility, the findings of the rapid assessment revealed a much bigger challenge.

Even though 99% of the population use a toilet, the findings of our rapid assessment show that close to 100% of the faecal waste accumulated was ending up somewhere in the environment. Although it is not clear where exactly the faecal waste that has been collected ends up, it can be safely assumed that most of it pollutes fields, rivers and tourist beaches as most of it never reaches a treatment facility.

These findings from Indonesia are not a cause for pessimism, though. It is a great start for a thorough understanding of where things go wrong, and the results are expected to be a wake-up call for city authorities. Using the results of the rapid assessment, authorities in Mataram now know which problems need to be addressed most urgently, and can start making the necessary plans for incremental change. This kind of assessment can hopefully help more local governments start considering the entire sanitation service chain and treat faecal waste more seriously.

Erick Baetings is a senior sanitation specialist, and Ingeborg Krukkert leads Asia programmes, at IRC, a water sanitation and hygiene think-and-do tank in the Netherlands.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow@GuardianGDP on Twitter, and have your say on issues around water in development using #H2Oideas.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion