Raising the Dead

At the bottom of the biggest underwater cave in the world, diving deeper than almost anyone had ever gone, Dave Shaw found the body of a young man who had disappeared ten years earlier. What happened after Shaw promised to go back is nearly unbelievable—unless you believe in ghosts.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

You’re about to read one of the Outside Classics, a series highlighting the best stories we’ve ever published, along with author interviews, where-are-they-now updates, and other exclusive bonus materials. Get access to all of the Outside Classics when you sign up for Outside+.

Ten minutes into his dive, Dave Shaw started to look for the bottom. Utter blackness pressed in on him from all sides, and he directed his high-intensity light downward, hoping for a flash of rock or mud. Shaw, a 50-year-old Aussie, was in an alien world, more than 800 feet below the surface pool that marks the entrance to Bushman’s Hole, a remote sinkhole in the Northern Cape province of South Africa and the third-deepest freshwater cave known to man.

Shaw’s stocky five-foot-ten body was encased in a black crushed-neoprene drysuit. On his back he carried a closed-circuit rebreather set, which, unlike traditional open-circuit scuba gear, was recycling the gas Shaw breathed, scrubbing out the carbon dioxide he exhaled and adding back oxygen. He carried six cylinders of gas, splayed alongside him like mutant appendages. On the surface, Shaw would barely have been able to move. But in the water, descending the shot line guiding him from the cave’s entrance to the bottom, he was weightless and graceful, a black creature with just a flash of skin showing behind his mask, gliding downward without emitting a single bubble to disrupt the ethereal silence.

Only two divers had ever been to this depth in Bushman’s before. One of them, a South African named Nuno Gomes, had claimed a world record in 1996 when he hit bottom, on open-circuit gear, at 927 feet. Gomes had turned immediately for the surface. But Shaw, a Cathay Pacific Airways pilot based in Hong Kong and a man who had become one of the most audacious explorers in cave diving, didn’t strive for depth alone. He planned to bottom out Bushman’s Hole at a depth that no rebreather had ever been taken, connect a light reel of cave line to the shot line, and then swim off to perform the sublime act of having a look around. At that moment late last October, cocooned in more than a billion gallons of water, Dave Shaw was a very happy man.

Recovering a body from the bottom of Bushman’s Hole was a feat of extraordinary danger, combining extreme depth and physical work, and Shaw and Shirley were just the guys to pull it off.

Shaw touched down on the cave’s sloping bottom well up from where Gomes had landed, clipped off the cave reel, and started swimming. There was no time to waste. Every minute he spent on the bottom—his VR3 dive computer said he was now approaching 886 feet—would add more than an hour of decompression time on the way up. Still, Shaw felt remarkably relaxed, sweeping his light left and right, reveling in the fact that he was the first human ever to lay line at this depth. Suddenly, he stopped. About 50 feet to his left, perfectly illuminated in the gin-clear water, was a human body. It was on its back, the arms reaching toward the surface. Shaw knew immediately who it was: Deon Dreyer, a 20-year-old South African who had blacked out deep in Bushman’s ten years earlier and disappeared. Divers had been keeping an eye out for him ever since.

Shaw turned immediately, unspooling cave line as he went. Up close, he could see that Deon’s tanks and dive harness, snugged around a black-and-tan wetsuit, appeared to be intact. Deon’s head and hands, exposed to the water, were skeletonized, but his mask was eerily in place on the skull. Thinking he should try to bring Deon back to the surface, Shaw wrapped his arms around the corpse and tried to lift. It didn’t move. Shaw knelt down and heaved again. Nothing. Deon’s air tanks and the battery pack for his light appeared to be firmly embedded in the mud underneath him, and Shaw was starting to pant from exertion.

This isn’t wise, he chastised himself. I’m at 270 meters and working too hard. He was also already a minute over his planned bottom time. Shaw quickly tied the cave reel to Deon’s tanks, so the body could be found again, and returned to the shot line to start his ascent.

Approaching 400 feet, almost an hour into the dive, Shaw met up with his close friend Don Shirley, a 48-year-old British expat who runs a technical-diving school in Badplaas, South Africa. After Shirley checked that Shaw was OK and retrieved some spare gas cylinders hanging on the shot line below, Shaw showed him an underwater slate on which he had written 270m, found body. Shirley’s eyebrows shot up inside his mask, and he reached out to shake his friend’s hand.

Shirley left Shaw, who had another eight hours and 40 minutes of decompression to complete. As Shirley ascended, it occurred to him that Shaw would not be able to resist coming back to try to recover Deon. Shirley would have been content to leave the body where it was, but Shaw was a man who dived to expand the limits of the possible. He had just hit a record depth on a rebreather, and now he had the opportunity to return a dead boy to his parents and, in the process, do something equally stunning: make the deepest body recovery in the history of diving.

“Dave felt very connected with Deon,” Shirley says. “He had found him, so it was like a personal thing that he should bring him back.”

When Shaw finally surfaced in the late-afternoon African sun, he removed his mask and said, “I want to try to take him out.”

Deep-water divers have always been the daredevils of the diving community, pushing far into the dark labyrinths of water-filled holes and extreme ocean depths. It’s a small global fraternity—there are no more than a dozen members—and in the history of recreational diving, only six people other than Shaw have ever pulled off successful dives below 820 feet. (More people have walked on the moon, Don Shirley likes to point out.) At least three ran into serious trouble in the process (including Nuno Gomes, who got stuck in the mud on the bottom of Bushman’s Hole for two minutes before escaping). And two have since died: American Sheck Exley, who drowned while diving the world’s deepest sinkhole, Mexico’s 1,080-foot-deep Zacatón, in April 1994; and Britain’s John Bennett, who disappeared while diving a wreck off the coast of South Korea in March 2004.

“Today extreme divers are far exceeding any reasonable physiology capabilities,” says American Tom Mount, a pioneer in technical diving and the owner of the Miami Shores, Florida–headquartered International Association of Nitrox and Technical Divers (IANTD). “Equipment can go to those depths, but your body might not be able to.”

Aside from the dangers of getting trapped or lost, breathing deep-dive gas mixes—usually a combination of helium, nitrogen, and oxygen known as trimix—at extreme underwater pressure can kill you in any number of ways. For example, at depth, oxygen can become toxic, and nitrogen acts like a narcotic—the deeper you go, the stupider you get. Divers compare narcosis to drinking martinis on an empty stomach, and, depending on the gas mix you’re using, at 800-plus feet you can feel like you’ve downed at least four or five of them all at once. Helium is no better; it can send you into nervous, twitching fits. Then, if you don’t breathe slowly and deeply, carbon dioxide can build up in your lungs and you’ll black out. And if you ascend too quickly, all the nitrogen and helium that has been forced into your tissues under pressure can fizz into tiny bubbles, causing a condition known as the bends, which can result in severe pain, paralysis, and death. To try to avoid getting the bends, extreme divers spend hours on ascent, sitting at targeted depths for carefully calculated periods of decompression to allow the gases to flush safely from their bodies. As divers say, if you do the depth, you do the time.

For any diver who can stomach the risks, Bushman’s Hole is world-class. It’s located on the privately owned Mount Carmel game farm, 11,000 acres of rolling, ocher-earthed veldt sparsely thatched with silky bushman grass and dotted with sun-baked termite mounds. Not until you top a small rise a few miles from the farm dwellings do you notice a break in the clean sweep of the land, where the earth starts to fall in on itself as if a giant hammer had come smashing down. The resulting crater is hundreds of feet from rim to rim and walled on one side by a sheer cliff. If you hike down the steep, stony path on the opposite side, you come to a small, swimming-pool-size basin of water, covered in a green carpet of duckweed. This is the entrance to Bushman’s Hole.

No one had any idea how deep Bushman’s was until Nuno Gomes arrived. On his first visit, in 1981, the Johannesburg-based Gomes dived to almost 250 feet, dropping down through a narrow chimney that opens up into an enormous chamber below 150 feet. In 1988, he set an African depth record of just over 400 feet, and Bushman’s reputation as a deep diver’s cave started to spread. In 1993, Sheck Exley showed up. Supported by a team that included Gomes, Exley became the first diver to hit bottom, touching down at 863 feet on the hole’s sloping floor.

During the Exley expedition, Gomes performed a sonar scan of the hole. It revealed Bushman’s to be the largest freshwater cave ever discovered, with a main chamber that was approximately 770 feet by 250 feet across and more than 870 feet deep. (Gomes later found a maximum depth of at least 927 feet.)

Diving Bushman’s is exhilarating. The narrow entrance is claustrophobic, but once you reach the vast main chamber, it’s like spacewalking. For a young cave diver like Deon Dreyer, it must have been irresistible. Deon grew up in the modest town of Vereeniging, about 35 miles south of Johannesburg, and loved adventure in all its forms. He shot his first buck at the age of ten. By 17 he was racing a souped-up car around local tracks, tinkering with his motorcycle, and designing obscenely loud car stereos. Another of his passions was diving. “He couldn’t sit still, never, ever, ever,” says his younger brother, Werner, now 27.

Deon had logged about 200 dives when he was invited to join some South Africa Cave Diving Association divers at Bushman’s Hole over the 1994 Christmas break. They planned a descent to 492 feet and asked Deon to dive support. He was thrilled. Two weeks before the expedition, Deon’s grandfather passed away. Sitting around a barbecue with his family one night, Deon spoke with boyish hubris. “He said if he had a choice of how to go out in life, he’d like to go out diving,” recalls his father, Theo, 51, the owner of a business that sells and services two-way radios.

Verna van Schaik & Peter Herbst

THE BIG DIVE TEAM: Support diver Peter Herbst, right, and Verna van Schaik, left, who ran the recovery expedition from the surface

THE BIG DIVE TEAM: Support diver Peter Herbst, right, and Verna van Schaik, left, who ran the recovery expedition from the surfaceDeon’s mother, Marie, a petite 50-year-old, begged Deon not to go. In 1993, Bushman’s Hole had already taken the life of a diver named Eben Leyden, who blacked out at 200 feet. (A dive buddy rushed him to the surface, but Leyden didn’t survive.) And then, on December 17, 1994, the hole claimed Deon Dreyer.

For Marie and Theo, the nightmare started with a policeman’s knock at the door. They rushed to Mount Carmel, where slowly the story came out. The team had been doing a practice dive. On the way back up, at 196 feet, Deon appeared to be fine, exchanging hand signals with his buddy. The group continued ascending. At 164 feet they suddenly noticed a light below them. A quick, confused diver count came up one short. Team leader Dietloff Giliomee wasn’t sure what was happening. Then another diver, in the eerie glow of his submersible light, dragged his finger across his throat. Giliomee desperately started swimming down but stopped when he realized the light below him was already more than 100 feet deeper and fading fast. “I decided it was a suicide chase,” he wrote in the accident report.

No one knows for sure what killed Deon. The best guess is deep-water blackout from carbon dioxide buildup. Two weeks after the accident, Theo paid to bring in a small, remotely operated sub used by the De Beers mining company. It found Deon’s dive helmet on the vast floor of Bushman’s, but there was no sign of his body. Resigning themselves to the idea that Deon would stay in the hole for eternity, Theo and Marie placed a commemorative plaque on a rock wall above the entry pool. “He had the most majestic grave in the country,” Theo says. “And I said, ‘Well, this will be his final resting place.’ ”

But on October 30, 2004, Dave Shaw called Theo and said, “I will go and fetch your son.” Theo immediately responded, “Yes, absolutely yes.” More than anything, he realized, he wanted to see his boy again.

If recovering Deon from the bottom of Bushman’s Hole was a feat of extraordinary ambition and danger, combining extreme depth with demanding work, Shaw and Shirley were just the guys to pull it off. On his first dive, in 1999, with his then-17-year-old son, Steven, in the Philippines, Shaw had found a sport whose challenges he couldn’t resist. He quickly pushed past the standard reef tours and went wreck diving. Soon enough he discovered the caves, and he was hooked.

As an airline pilot, Shaw could dive all over the world—in Asia, the United States, Mexico, and South Africa. He was born in the small town of Katanning, in Western Australia, and from the age of three, when he built his first toy aircraft out of cardboard, Shaw knew he wanted to fly. By the time he was 18, in 1973, he was working as a crop duster. That same year he met the Melbourne-raised Ann Broughton at a youth camp in Perth. He took her up in an airplane on their first date, and 20 months later they were married. In 1981, Shaw became a missionary pilot, moving with Ann to Papua New Guinea, where Steven was born. A daughter, Lisa, followed in 1983, and the Shaws relocated briefly to Tanzania before moving to New South Wales, Australia, where eventually Shaw began flying corporate jets. In 1989, he settled in with Cathay Pacific, moving his family to Hong Kong.

Shaw loved to poke around deep underwater, so he was committed to the closed-circuit rebreather for its remarkable efficiency and the warm, moist gas recycling produces. The oxygen supply is automatically monitored and adjusted by a digital controller strapped to a forearm, and pretty much the only oxygen consumed is that which the diver metabolizes. In contrast, divers using traditional open-circuit scuba (the majority of divers today) inhale ice-cold mixes and exhale huge volumes of gas into the water. (Rebreather divers like to call them “bubble blowers.”) As a result, extreme open-circuit divers often need a dozen or more gas cylinders, constantly court hypothermia, and, without automatic control of their oxygen levels, end up breathing—and absorbing—more helium and nitrogen, running up a greater decompression tab. When Nuno Gomes went to the bottom of Bushman’s Hole on open circuit in 1996, he didn’t hang around at all, used more than 54,000 liters of gas, and had to spend almost 12 hours in the water. When Shaw went to the bottom on his rebreather, he tooled around exploring, used only 5,800 liters of gas, and got back to the surface in nine hours and 40 minutes.

The chief drawbacks to rebreathers are that they are expensive (upwards of $5,000), require the diver to constantly monitor the digital controller settings (open-circuit divers just have to breathe), and, until Shaw came along, had not been proved at great depths. But Shaw was convinced that rebreathers were the future of diving. In 2003, he purchased a rare Mk15.5 rebreather, developed by the U.S. Navy for deep submarine evacuation, and modified it with a Hammerhead controller that he filled with paraffin oil, as a sort of internal shock absorber that would help the components withstand intense pressures. Then he set about diving his custom rig to successively greater depths.

Don Shirley, an understated man with steel-frame glasses and a scraggly beard, was a kindred spirit. He grew up in Surrey, England, and spent 22 years as an electronics specialist in the British Army, which took him through the Falklands War and to the Persian Gulf. He dived every spare minute he had, specializing in deep wrecks off the coast of Britain. In 1997, he retired from the army and moved to South Africa, looking to start a new life as a technical-diving trainer in an exotic English-speaking land. He and a partner set up the South African franchise of IANTD, alongside a deep, flooded asbestos mine in the beautiful grassy hills a couple hundred miles east of Johannesburg. He dubbed the spot Komati Springs, spent hundreds of hours a year in the water, teaching technical and cave diving, and developed the mine, with its deep shafts, into a premier dive site. In 2003, he married Andre Truter, a feisty 38-year-old Afrikaner with short brown hair and a sly smile. Together they live in a thatch-roofed bungalow, surrounded by a pack of rambunctious dogs with names like Sheck and Argon.

In the fall of 2002, a bearded man with an Australian twang appeared at Shirley’s dive center. “Hi, I’m Dave Shaw,” the man said. “Do you mind if I go dive your hole?” Shirley sized up the bluff Aussie and liked what he saw. Soon Shaw was flying in regularly to dive, and Shirley went with him whenever he had time. In October 2003, at Komati Springs, Shaw set a rebreather cave record of 597 feet, with Shirley diving backup. Two days later, Shirley, with Shaw just behind him, became the first diver to reach the very end of the mine’s deepest shaft, at 610 feet. Shaw and Shirley had logged more than a hundred hours underwater together in the nearly two and a half years they’d known each other. “It was stunning being in the water with Dave, very relaxed,” Shirley says.

Shirley introduced Shaw to the enticing depths of Bushman’s in June 2004. Shaw turned up with his modified Mk15.5 and dived it to 725 feet, another world record for a closed-circuit rebreather in a cave. His DUI drysuit and Thinsulate underwear kept him warm. He peed happily into the water via a valve in his drysuit that had a catheter running to a condom (informally known as “the Urinator”), and topped up, intermittently pulling his regulator out of his mouth, on candy bars and water lowered in a string bag at shallow decompression stops. He fell in love with the place.

In November 2004, back home in his apartment in Hong Kong, Shaw was in almost daily e-mail and phone contact with Shirley. The Big Dive, as they started to call it, was set for early January, and one of the most elusive questions was the condition of Deon’s body. The forensics experts they consulted weren’t sure but guessed the corpse would be mostly bone. Shaw decided he’d better try to get it into a body bag for the trip to the surface or risk having it fall apart. Together with Ann, he designed a silk bag with drawstrings, long enough to fit over Deon’s fins.

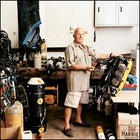

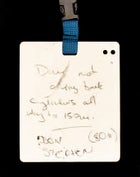

Lo Vingerling

Lo Vingerling, support diver and member of the cave brotherhood, at home with his gear

Lo Vingerling, support diver and member of the cave brotherhood, at home with his gearAnn, a 49-year-old deputy head principal at Hong Kong’s German Swiss International School, was nervous about the dangers her husband faced. “I want someone to ring me as soon as you are on your way up,” she insisted. Shaw agreed but gave Ann the impression the dive would be taking place a day later than scheduled. That way, he could just call her when he was back on the surface and say, “Don’t worry. It’s all over and I’m fine.” If he wasn’t fine, he gently told Ann, he would arrange to have someone call Michael Vickers, their minister at Hong Kong’s Anglican Resurrection Church.

On the evening of Saturday, January 1, Ann made the 45-minute drive to Hong Kong’s Chep Lap Kok airport with 250 pounds of dive gear in her car. Shaw had been flying that day, and she met him at the Cathay Pacific offices and drove him to the departure area for his flight to South Africa. They sat together in a coffee bar. “You’re not crying, are you?” he asked. “No,” Ann replied bravely. Shaw got up to leave for his flight. He didn’t say, “I love you.” He didn’t need to. She knew.

Shaw arrived in Johannesburg six days before the dive. His first stop was Komati Springs, where he practiced getting a body into the bag underwater, with Shirley playing the part of Deon’s corpse. At 66 feet, it went smoothly, taking Shaw only a couple of minutes. A day later, he and Shirley drove to Mount Carmel, where seven South African rebreather divers, handpicked by Shirley, and a police team from Cape Town and Pretoria (since there was a dead body involved) were assembling. The dive would go off on the coming Saturday, January 8, and Shirley’s dive plan was like an underwater symphony. Shaw was looking at a dive that would last roughly 12 hours, and would hit the water around 6 a.m. All the other divers would key off Shaw’s dive time and head for specific target depths either to help look after Shaw or pass Deon’s body to the surface. The first diver Shaw would meet on the way back up was Shirley, at 725 feet. He would hand the body bag over, and, if things went well, Deon would be out of the water about 80 minutes after Shaw’s dive had started.

Shirley had done everything in his power to minimize the risks. He planned to have 35 backup cylinders of gas in the water—enough so that he, Shaw, and even some support divers could survive total rebreather failure. He arranged for a rope-and-sling system to be set up that could haul a diver on a stretcher up the cliffs of the hole to a recompression chamber that the police trucked in. To cope with any medical emergencies, Shirley had recruited a doctor—Jack Meintjies, a specialist in diving physiology at the University of Stellenbosch, outside Cape Town—to be on hand. When Meintjies realized that up to nine divers would be in the water, and learned the depths they would be going to, he almost backed out. “There were too many potential bodies. You are dealing with multiple divers going deep, and that’s serious,” Meintjies says.

Shaw, for one, was quietly confident. At Mount Carmel, he stressed repeatedly that the effort was an “attempted” body recovery. “The dive is huge,” he told a collection of reporters and cameramen gathered a day before the dive. “No one has ever attempted anything even vaguely approximating a body recovery from these sorts of depths.” He also talked about his motivation with the team. “I think what you are doing for the Dreyers is great,” said Peter “Big B” Herbst, a 42-year-old dive instructor and the owner of Reef Divers, a dive shop and tour operator in Pretoria. Shaw looked at him, winked, and said, “Face it, B, we’re doing this for the adventure of it.”

Shaw did have one wrinkle to sort out. He had partnered up with South African documentary filmmaker Gordon Hiles to chronicle the recovery of Deon. Hiles had designed an underwater camera housing for a lightweight, low-light Sony HC20 Handy- cam and attached it to a Petzl climbing helmet. Shaw was not used to wearing a helmet. He liked to carry a high-intensity light on the back of his hand, and if he needed both hands underwater, Shaw would normally sling the light and cable around his neck so it wouldn’t snag on anything. The helmet cam would make it hard to do that. Shaw tried the device in the swimming pool at Mount Carmel and decided he was comfortable with the design and weight. He told Hiles that, instead of slinging his light around his neck, he would occasionally set it out to the side.

“The most important person on this dive is you,” Shaw told the team. “If you have a problem, deal with your problem and forget about me. It’s better to have one person dead than two.”

Three days before the dive, Shaw carried the camera on an acclimatization dive to 500 feet. It came out in perfect running order. “A very impressive bit of gear,” Shaw said to Hiles. “I’m sure you’ll be impressed with my video footage as well.” Everyone laughed.

The divers gathered for one last briefing on Friday. It was a warm, beautiful evening, and Shaw had some final points to make. “The most important person on this dive is you. If you have a problem, deal with your problem and forget about me,” he told the team. “It’s better to have one person dead than two.” He had a separate, private conversation with Shirley, who had upgraded his rebreather for the dive with an oil-filled Hammerhead controller so he could get all the way to the bottom of Bushman’s if he had to. Shirley had asked his friend, “If you have problems, do you want me to come down?”

Shaw considered the question and answered, “Yes, but only come down if I signal.”

Shirley and Shaw had one last message for the gathered team. “If Dave doesn’t make it, if I don’t make it, we stay there,” said Shirley. “That’s the end of the story. We don’t want to be recovered.”

At 4 A.M. on Saturday, January 8, Shaw and Shirley rose in the dark to prepare for the dive. It had been a rough night for Shirley. The previous evening, as he was changing the battery on his new Hammerhead controller, a wire snapped. Without the unit, he wouldn’t be able to make the dive. Shirley was devastated. Shaw felt deeply for his friend but was prepared to proceed without him. He put Shirley and Peter Herbst in touch with Juergensen Marine, the Hammerhead manufacturer. At 9 p.m.—the cutoff time he had set for himself—Shaw went to bed. With the help of Juergensen, a soldering iron, and some tinfoil, Herbst managed to jury-rig a fix. The Hammerhead powered up, and Shirley was a go again.

“WE SAW HIM”: Theo and Marie Dreyer, whose son Deon died in Bushman’s Hole, at their home near Vereeniging, South Africa.

“WE SAW HIM”: Theo and Marie Dreyer, whose son Deon died in Bushman’s Hole, at their home near Vereeniging, South Africa.In the gray predawn light, Shaw and Shirley began the ten-minute drive to the hole, listening to iPods to relax. Shaw had bought two in Hong Kong, loaded them with mixes he called Deep Cave 1 and Deep Cave 2, and given one to Shirley as a gift. (Shirley’s favorite tune for the ride to the crater was Led Zeppelin’s “Whole Lotta Love.”) At the water, they started squeezing into their drysuits. Knowing how long he might be underwater, Shirley added an adult diaper to his ensemble. The rest of the team—the support divers, the police divers, the paramedics—assembled as well, and the rocky, uneven ground around the surface pool became crowded, dive equipment spilling over every flat surface. Verna van Schaik, 35, a South African who had set the outright women’s depth record of 725 feet at Bushman’s in October, settled in with a large sheaf of dive tables. Shirley had asked her to run the dive as surface marshal, and van Schaik, who has magenta hair and a dolphin tattoo on her right ankle, was hoping she was going to have an easy day.

At 6:13 a.m., video camera whirring quietly on his head, Shaw shook Shirley’s hand, said, “I’ll see you in 20 minutes,” and ducked into the dark waters of Bushman’s Hole. A few minutes later, Theo and Marie Dreyer made their way to the water’s edge. They had come late so that Shaw wouldn’t feel any additional pressure to bring Deon back.

Shaw dropped quickly, letting the shot line squeak through his fingers. He hit the bottom in just over 11 minutes, more than a minute and a half faster than he had planned, and immediately started swimming along the cave line. As soon as the corpse loomed ahead, he pulled out the body bag. Then he knelt alongside Deon and went to work. He almost certainly could feel the narcosis kicking in. The helium and reduced nitrogen of his trimix would have limited the effect, but it was probably still as if he had downed four or five martinis. He had been on the bottom of Bushman’s Hole, at 886 feet, for just over a minute.

Thirteen minutes after Shaw submerged, Shirley got the go signal from van Schaik and dropped toward his rendezvous point with Shaw, at 725 feet. Approaching 500 feet, he looked down. The water was so clear he could see Shaw’s light almost 400 feet below him. It was about where he expected it would be, in the region of the shot line. There was only one problem: The light wasn’t moving. Shirley knew instantly that something had gone very wrong. By this time, more than 20 minutes into his dive, Shaw should have been ascending. Shirley should have seen bubbles burbling up as Shaw vented the expanding gases in his rebreather and drysuit. But there was no movement. No bubbles. Nothing but a lonely, still light.

Shaw hit the bottom just over 11 minutes into his dive. He knelt alongside Deon and went to work. He almost certainly could feel the narcosis kicking in, as if he had downed four or five martinis.

Shaw hit the bottom just over 11 minutes into his dive. He knelt alongside Deon and went to work. He almost certainly could feel the narcosis kicking in, as if he had downed four or five martinis.

There is no room for emotion or panic in the bowels of a dark hole. Shirley stayed calm, his actions becoming almost automatic. Shaw hadn’t signaled for help, but Shirley would be going to the bottom. A motionless diver at 886 feet is almost certainly a dead diver, but it was Dave Shaw down there. Shirley had to see if there was anything he could do, or at least clip Shaw to the shot line so his body could be recovered. OK, here we go, then, he said to himself.

At about 800 feet, deeper than he had ever been, Shirley heard the slight, sharp crack of enormous pressure crushing something, and then there was a thud. He looked down: The Hammerhead controller on his left forearm was a wreck. Without it, Shirley would have to constantly monitor the oxygen levels in his rebreather and inject oxygen into his breathing loop manually. It was a full-time occupation, an emergency routine at a life-threatening depth. Shirley was certain that if he went down to Shaw he would join him for eternity. He got his rebreather back under control and started back up the shot line, flipping through the alternate decompression profiles he was carrying with him on slates. He was facing at least another ten hours in the water. After a few minutes, Shaw’s light was swallowed by the darkness below him.

Back on the surface, van Schaik and the crowd around the hole had no idea what was going on far beneath them. Twenty-nine minutes after Shaw had gone under (and about six minutes after Shirley had seen that his light was not moving), support divers Dusan Stojakovic, 48, and Mark Andrews, 39, started their dive to rendezvous with Shaw at 492 feet. As they closed on their target depth, they realized there were no lights coming up, and no sign of Shirley or Shaw. Their plan called for them to wait two to four minutes. They stayed for six. Then it was time to go. “There’s no heroics in this diving,” Stojakovic says bluntly. “You dive your plan.”

Before Andrews and Stojakovic started up, they peered once more into the void. This time they could see a light, but they couldn’t tell who it was. Andrews took out an underwater slate and wrote, DID NOT MEET D + D, @ 150 [METERS] FOR 6 MIN. 1 LIGHT BELOW? NOT SURE D’S LIGHT OFF. On the way up, they passed Peter Herbst, and then Lo Vingerling, 60, another support diver, who were on their way down. They showed each the slate and continued ascending. They needed to get the slate to the surface.

Herbst is a bearish Afrikaner with unruly graying hair and a love of a good joke. He’s also a first-rate diver who never shies from a tough job. The single light meant there was trouble, and without hesitation Herbst descended past his target of 275 feet. Whoever was underneath him might need help, and Shirley was one of his best friends. Just a little deeper, just a little deeper, he kept telling himself. As the diver got closer he found himself praying, Please, please, God, let it be Don.

Just past 400 feet, Herbst pulled even. It was Shirley. Sorry, Dave, Herbst silently apologized. He flashed Shirley the OK sign and got one back. Then Shirley asked Herbst for a slate. He scribbled on it for a second and returned it. It read, DAVE NOT COMING BACK. Now it really hit Herbst. No Deon. No Dave. Reflexively, he peered deep into the hole. He saw nothing, just blackness. He checked Shirley again, and Shirley indicated that he should head up. Lo Vingerling was the next diver to reach Shirley. He signaled that he would drop down to do a last sweep for Shaw. Shirley stopped him, then drew his hand across his throat.

On the surface, the Dreyers waited nervously. It had been more than an hour since Shaw submerged, and the police divers were due to return with their son’s body any minute. Theo wrapped his arms around Marie, and they peered into the dark pool. A nervous hush settled over the group. It was broken by the rattling of stones inside a plastic Energade bottle. The bottle was attached to a line dropping 20 feet into the hole, so that the divers could send slates up as they sat decompressing.

It was the slate from Andrews and Stojakovic, and was passed to van Schaik. Somehow, instead of “1 light below,” van Schaik understood the slate to read “no lights below.” She assumed it was saying that both Shaw and Shirley were gone. Within minutes, the police divers surfaced, empty-handed. In an instant, the entire, noble enterprise fell apart. Divers were dying. There was 30 seconds of stunned silence around the hole, then van Schaik calmly announced, “OK, we are on our emergency plan.”

Within 20 minutes another slate arrived. It was from Shirley, and it had been raced to the surface by the next diver to reach him, Stephen Sander, 39, a former police-special-forces diver. DAVE NOT COMING BACK, it stated bluntly, repeating the slate Shirley had given to Herbst. On the flip side it detailed Shirley’s new decompression profile. Van Schaik felt some relief—one of her two dead divers was alive—but glancing at the figures on the slate, she could see that Shirley had gone very deep and would run the risk of getting bent as he came up.

For the Dreyers it had been a tragic half-hour. A day that had started out promising the recovery of their son’s body was now going to end with Shaw and Deon both at the bottom of Bushman’s Hole. The Dreyers backed away from the water, helpless to do anything, and made their way to the farmhouse. Marie was in agony, crying and thinking about Shaw’s wife and family. She wandered into Shaw’s room and saw his shoes, wallet, cell phone, and clothes, all neatly laid out. It’s like he’s coming back soon to use it all again, Marie thought. But she knew he wasn’t.

Derek Hughes, an underwater cameraman who was working with Gordon Hiles, also left. Before the dive, Shaw had asked him to call Michael Vickers, the Shaws’ minister, if there was trouble. Hughes climbed to the top of the crater to get cell-phone reception and placed the call. Vickers asked him if he was sure Shaw wasn’t coming back. Hughes waited another two hours before making the trip up the crater to call Vickers again. He was sure.

Dave Shaw.

Dave Shaw.It was 7 p.m. Saturday evening in Hong Kong, and Ann Shaw was in her living room. Her 21-year-old daughter, Lisa, was with her, on break from the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology. The doorbell rang, and Ann opened the door to see Vickers, accompanied by two friends from church. Ann thought the dive wasn’t taking place until the next day, but as soon as she saw the somber group, she knew. Vickers explained that Dave was five hours late. He suggested there was still a chance he could reappear. “Oh, no, he won’t,” Ann replied. “Not if he’s been down there so long.”

Ann, who has a deep faith in God, tried to believe that there was some higher purpose in what was happening. More than anything, though, she was struck by how completely her life had changed in the brief time it took Vickers to relay the news. The last time she’d had that feeling was 30 years earlier, at 19, as she walked down the aisle to be married, with Dave Shaw, himself just 20, waiting for her at the altar.

Back at the hole, van Schaik didn’t have time to think much about Shaw. With five other divers in the water and only two reserve divers on the surface, she had to focus on Don Shirley. She sent Gerhard Du Preez, 31, into the hole to find him, with instructions to check everyone on his way down. Du Preez found Shirley just below the ceiling of the main chamber, checked that he was OK, then turned immediately for the surface to report back.

Alone again, Shirley continued his retreat. As he approached the chamber ceiling at about 164 feet, he started feeling faint. Instinct told him to get off his rebreather and onto his open-circuit bailout before he lost consciousness. He stuffed the regulator into his mouth, and as soon as he did, the cave started to spin around him. Shirley didn’t know it yet, but a small bubble of helium had formed in his left inner ear, causing extreme vertigo. He was in a washing machine, and off the shot line. In the dark, all he could see with his light as he spun was black, followed by the flash of the cave roof, then black. He saw a flash of white go by, and then again. It was the shot line, and without thinking he thrust out his hand to grab it. That grab kept him alive. If he had missed, he would have drifted off, lost in the blackness. Up or down, it wouldn’t really have mattered. Depth or the bends would have finished him, and van Schaik and her divers would have returned to an empty line.

The washing machine finally slowed just long enough for Shirley to read the backlit screen of his primary VR3. It showed he had come up to 114 feet. It also warned him that he needed to be down at 151 feet. Hand over hand, Shirley descended. As he reached his new depth, nausea hit him and he started to vomit. Shirley would feel the heave coming, pull the regulator from his mouth, throw up, and then replace the regulator. Fighting the vertigo and nausea, he managed to grab some spare gas cylinders from the cluster clipped onto the shot line nearby. The thought that he might die never occurred to him. I will survive, I will survive, he kept telling himself.

After about 20 minutes, Truwin Laas, 31, van Schaik’s second reserve diver, appeared. Shirley scratched on his slate, I’M HAVING A BAD TIME. I’VE GOT VERTIGO AND I’M VOMITING. Laas made sure Shirley was breathing the right gas mix for the depth, decided he was stable, and left quickly to update van Schaik. Shirley, alone again, started cycling repeatedly through a subroutine of survival, asking himself, Where should I be now? How long should I be here? And where do I have to go? Each breath was a conscious act that got harder as he tired. Suck, hold, exhale. Suck, hold, exhale. I will survive. I will survive.

Now the marathon began. Van Schaik started cycling divers down to stay with Shirley. Du Preez, Laas, Sander, and Vingerling dived repeatedly that day, racking up three or four dives apiece despite the risk of getting the bends themselves. (Herbst, who was out of action for hours with a suspected minor bend, went down once more; Andrews and Stojakovic had been too deep to dive again.) The divers clipped Shirley to the shot line in case he convulsed or passed out, unclipping him only to move him from one decompression stop to another. Every movement brought a new round of vomiting. “It was heartbreaking to hear,” Vingerling says, mimicking the spastic violence of Shirley’s dry heaves.

Before the dive, Shirley had told the team that if anything went wrong, his wife, Andre, was to be given the bad news straight and fast. Andre, who had stayed behind at Komati Springs to run the dive center, had been getting regular updates. After one call, a slate was taken to Shirley. MESSAGE FROM ANDRE, I LOVE YOU, it read, and then, YOU’D BETTER HANG IN THERE OR ELSE.

After more than ten hours in the water, Shirley finally reached a depth of 20 feet. He was exhausted and approaching hypothermia, but he stayed there decompressing for almost two hours. The next circle of hell was at just ten feet and had to be endured, according to the tables, for a full two hours and 20 minutes. As soon as Shirley settled in, a sharp pain flared in his left leg, a sign that more bends could be on the way. It was time to take his chances on the surface. LOWER LEFT LEG HURT. COULD BE LACK OF USE? he wrote on a slate. Soon after, Sander appeared. I’M HERE TO TAKE YOU HOME, he wrote.

Shirley was carried out. He had been in Bushman’s Hole almost 12 and a half hours. “Don’t cut the drysuit,” he managed to growl when he saw Du Preez coming at him with a pair of shears. Shirley was winched up the cliff face, and within 22 minutes he was in the recompression chamber.

Over the next few days, as word spread of Shaw’s death, the Dreyers and most of the dive team went home. Andre Shirley arrived on Sunday, after driving all night from Badplaas, to take her husband for additional recompression treatments in Pretoria. But Herbst stayed at the hole, and he was in a grim mood. It had been left to him to retrieve all the lines and gas cylinders that still hung in Bushman’s depths, work he had started on Monday. By Wednesday, he was ready to go after the deepest cylinders, and he had called in his Afrikaner diving buddy Petrus Roux to help, with the police assisting at shallower depths. Standing at the water’s edge, the police team held an impromptu memorial service for Shaw. Police diving superintendent Ernst Strydom and Roux read from the Bible. Herbst hadn’t planned to say anything, but emotion gripped him, and a few words came.

“I’m going to miss you, mate,” he said, as if Shaw could hear. “It’s a good place. Rest here, stay here.” The group sang “Amazing Grace” as black clouds threatened rain. And then Herbst and Roux dived into the hole.

They dropped to 300 feet and attached lifting buoys to the shot line to raise the cylinders still at 500 feet to a more manageable depth. When they returned to the surface, they were approached by police diver Gert Nel, who had been helping to clear lines in the chimney. “Did you see them?” Nel asked quietly. “See what?” Herbst asked. “The bodies,” Nel said. “We saw Deon and Dave stuck in the cave at 20 meters.”

Herbst rested up and returned to the water. As soon as he cleared the narrow neck of the chimney, his cave light locked on to Shaw, floating eerily upright, his arms spread wide and the back of his head and shoulders jammed against the ceiling. Shaw’s light was hanging below. Looped around it was the cave line he had attached to Deon in October, and cradled almost perfectly in the line, its legs hanging down as if on a swing, was the headless body of Deon Dreyer. Herbst realized that Shaw’s light must’ve gotten tangled in the cave line. When Herbst and Roux had lifted the shot line with the buoys, it had pulled the cave line—and with it Deon and Shaw—off the bottom. As Shaw ascended, the gases in his body, as well as those in his suit, rebreather, and buoyancy wing, had started to expand. Up he had gone, dragging Deon with him.

Herbst brought Deon out first. The police team laid a white body bag along the water’s edge and lifted Deon into it. There was a surprising firmness under the wetsuit, and Strydom was shocked to get a whiff of rotting flesh. One of Deon’s flippered feet fell off. A policeman tossed it into the bag alongside the body, and the zipper was closed. Shaw had died doing it, but Deon’s body had finally been taken back from Bushman’s Hole.

Shaw was recovered next. It was a distressing job. His body was grotesquely swollen from the change of depth and pressure, and it was locked by rigor mortis in the free-fall position. Herbst, standing in the surface pool, had to cut Shaw out of his equipment. “That was quite bad,” he says, choking up.

Herbst cut the helmet cam free, too. Gordon Hiles, who had been filming the morning’s work, was relieved to see that the camera’s housing was still intact. Herbst was exhausted, with a pounding headache. He needed to call Don Shirley and Ann Shaw. But more than anything, he wanted to see what was on that video.

It’s not an easy thing to watch a person die, especially if that person is a friend. Less than an hour after the helmet cam was removed from Shaw’s head, as Hiles made a copy of the video for the police at the top of the crater, Herbst watched the film of Shaw’s last dive. Later, he and Shirley (who calls it “a snuff tape”) examined it frame by frame, backward and forward, multiple times, to try and understand every nuance of Shaw’s death.

The picture is dark, and sometimes hard to see. But along with the sounds of Shaw’s breathing, picked up with perfect clarity by the camera in the stillness of the cave, the video tells the tale of Shaw’s final moments. When Shaw reaches the body of Deon Dreyer, he is 12 minutes and 22 seconds into the dive, and he’s been on the bottom for just over a minute. He pulls the body bag out and starts to try and work it over Deon’s legs. As he does, a cloud of silt obscures the picture. When it clears, Deon’s body, its head having fallen off, is floating in front of Shaw.

This was totally unexpected. Deon, as it turned out, was not completely skeletal, and he was no longer stuck in the silt. Instead of decomposing, his corpse had mummified into a soaplike composition that gave it mass and neutral buoyancy. And for some reason—no one has an explanation—the body had become unstuck from the mud as soon as Shaw started working on it. “The fact that the body was now loose, and not pinned to the ground, was not one of the scenarios that we had thought about,” Shirley sighs. “The body was not meant to be floating.” It’s a lot easier to slip a bag over an immobile body than a body floating and rolling in front of you at 886 feet.

Shaw starts fumbling and, for the first time, lets out an audible grunt of effort.

Herbst, listening intently through headphones, heard the steadily increasing distress in Shaw’s breathing and knew there was trouble coming. “Breathe slower, man, breathe slower,” he urged out loud. Watching the video with a clear head, it is hard not to wonder why Shaw didn’t just turn around right then and abandon the dive. In October, he had turned for the surface as soon as his breathing rate increased. Now he was panting, and Deon, who was attached to the cave line, was floating free. The body could have been pulled up. “All the options involved putting the bag on,” Shirley explains. “He’s sticking with his plan. Which is what you’ve got to do.” Still, when Shirley first saw the video, he couldn’t stop himself from pleading, “Leave it, leave it, leave the body now. It’s loose and can come up.”

Shaw, however, is responding only to the pounding of his narcosis and his determination to finish the job. He keeps working to control the body, letting go of his cave light so he can use both hands. Deon is rolling and turning in front of him, resisting Shaw’s efforts to get him into the bag. Shaw has been at it for two minutes, and the cave line is seemingly everywhere. It snags on his cave light, and Shaw pauses to clear it.

At this, Shirley and Herbst bridled. A cave diver should never let gear float loose. “It’s a recipe for disaster,” says Shirley, who will always regret not being present when Shaw told Hiles he would put the light to the side at times. “Do not do that,” he would have warned him.

For the Dreyers, a day that had started out promising a recovery of their son’s body was now going to end with Dave Shaw and Deon on the bottom of Bushman’s Hole. They backed away, helpless.

Now Shaw is acting confused. He is working at the torso, instead of the feet. His movements have lost purpose. After more than two and a half minutes of work—and three minutes and 49 seconds on the bottom—Shaw pulls his shears out, fumbling to open them. The plan was for him to cut the dive tanks away as he rolled the bag over Deon. Shaw’s breathing rate continues to increase. Suddenly he loses his footing on the sloping bottom. He scrambles back to the body in a cloud of silt. The grunts of effort, hateful little bursts of sound, are painfully frequent.

Shirley and Herbst guess that Shaw’s narcosis was then closer to six or seven martinis. “You focus on the one thing. You don’t focus on the dive anymore,” Herbst says. “The one thing becomes everything. And I think with Dave it became the body, the body, the body.”

Still, Shaw keeps checking the time on his dive computer. After five and a half minutes on the bottom, he’s aware enough to know he has to leave, but he doesn’t get far. The video shows the bottom moving beneath him. Then Shaw’s forward progress stops. His errant cave light has apparently snagged the cave line tied to Deon’s tanks. Shaw knows he has caught something and turns awkwardly. His breathing starts to sound desperate. He pulls at the cat’s cradle of cave line, as if trying to sort it out. Every breath is now a sharp grunt. Shaw struggles to move forward again but is anchored by the weight of Deon’s body. The shears are still in his hand, but he never cuts anything. The pace of his breathing keeps accelerating, and there is a tragic, gasping quality to it, so painful to listen to that Herbst and Shirley will no longer watch the video with sound.

Twenty-one minutes into the dive, the sounds finally start to fade. Dave Shaw, with carbon dioxide suffusing his lungs, is starting to pass out. He is dying. It’s heartbreaking to watch. A minute later there is no movement.

Don Shirley survived that day, but he didn’t walk away unscathed. He emerged from the recompression chamber at Bushman’s, which was pressurized to a depth of 98 feet to shrink the helium bubble in his head, after seven hours, disoriented and barely able to stand. He was so weak that Herbst dragged a mattress over from the police camp so Shirley could sleep right there. Over the next two weeks, he endured ten more chamber sessions, for a total of 27 hours of treatment. It was more than a month before he could think clearly or walk down a crowded street without his perception and balance running haywire. “When I first saw him, I got a hell of a shock,” Andre Shirley says. “He could not walk without support, and his thinking patterns had been affected. He would sound sane, but two minutes later he would forget what he’d said.”

Shirley has improved with time, but the helium bend left him with permanent damage that has impaired his balance. In May he went diving again for the first time, with Peter Herbst hovering protectively alongside. He closed his eyes, turned somersaults, and with relief discovered that the Big Dive had not taken one of the things he loves most. “A cave is a place where I live,” Shirley says.

A week after Shaw died, Gordon Hiles brought the video to a guest house in Pretoria, where Shirley was staying while undergoing recompression treatment at the Eugene Marais Hospital, and Shirley finally watched it. “It was difficult to see, but I really wanted to know firsthand what went on,” he says. Later that day, Shirley took the video to the hospital, where he met with Herbst and Dr. Frans Cronje, medical director of Divers Alert Network Southern Africa, who was overseeing Shirley’s treatment and assisting with the official accident investigation. They watched the video on a large screen and spent hours poring over every detail.

“You focus on the one thing,” Herbst says. “You don’t focus on the dive anymore. The one thing becomes everything. And I think with Dave it became the body, the body, the body.”

Shirley was so focused on what he was watching that he started mimicking Shaw’s breathing. Then, determined to “see for myself what happened,” Shirley volunteered for an unusual experiment. As Cronje carefully observed, Shirley sat with a CO2 monitor in his mouth and headphones on his ears, watching the video one more time. Every time Shaw breathed, Shirley breathed. Eventually Shirley was huffing through 36 shallow, extremely rapid breaths a minute.

“There was extreme hyperventilation,” Cronje says. “On a rebreather at that depth, it would have been very ineffective.” Shirley’s breathing became so distorted that by the time Shaw faded to just six breaths per minute and then lost consciousness, Shirley was also on the verge of blacking out. His hands were weak and he could barely move. Cronje concluded that Shaw had passed out from carbon dioxide buildup and eventually drowned.

It took Shirley a full half-hour to bring his breathing back under control.

“I actually died with Dave,” he says.

Nuno Gomes is the last person alive today who knows what it’s like to dive to the bottom of Bushman’s Hole, and he understands why Shaw had trouble reacting to a body that was suddenly floating instead of anchored. “You don’t think of a new plan while you are down there. It doesn’t work. Your mind is clouded. You cannot do it,” Gomes says. But he also wonders whether Shaw should have done more buildup dives to increase his tolerance for narcosis—much the way a climber will try to acclimatize to altitude—and his ability to recognize when it reaches dangerous levels. “When he started putting the body in the bag and it didn’t work, he should have immediately turned around and left,” Gomes says.

Gomes is an open-circuit diver, and his priority is setting records. (In June, he reclaimed the world depth record, reaching 1,044 feet in the Red Sea.) “I didn’t think it was worth the risk of a diver losing his life to recover the remains of Deon Dreyer,” he says flatly. Even so, Gomes honors Shaw as a fallen comrade. “It was a noble dive, a heroic dive. He did what he believed in, and I’ve got to say he had a lot of courage,” Gomes says. “At the end of the day, he achieved what he wanted to achieve, even though he paid for it with his life.”

None of the divers who were with Shaw in Bushman’s Hole think the dive was reckless. As support diver Mark Andrews puts it, “If you asked me about the chances before the dive, I’d have said there is a 99 percent chance of success, and a 1 percent chance he’ll have to leave the body. And zero percent that Dave wasn’t coming back.”

Verna van Schaik, who is used to people telling her she is pushing too deep, is sorry Shaw died but not sorry for him. “Dave was going to go back,” she says. “The fact that Deon was there just made it more interesting and more exciting. Dave knew the risks. They were his risks, and he took them.”

Every diver there that day will keep diving, and instead of second-guessing Shaw, they say they are proud of him. “Dave took rebreather diving where it has never been before. People never knew about [rebreathers] until he died showing what can be done,” Peter Herbst says. “Two hundred meters [656 feet] was a damned deep dive on a rebreather. This guy went half as deep again. He made the envelope bigger.”

Ten days after Bushman’s Hole gave the bodies back, Theo and Marie Dreyer went to see their son. When the morgue attendant asked them to step in, Marie wasn’t sure what to expect. When she saw a fully fleshed-out body, her tears stopped, and she felt happy. There was no head, but lying in front of her was her boy. Theo marveled that Deon’s legs still held their athletic shape. Marie couldn’t believe he was still in his Jockey underwear. “We saw him,” she explains, her eyes shining. Overwhelmed, she stepped forward and took her dead son in her arms.

Ann Shaw had hoped her husband would rest forever in Bushman’s Hole. When Herbst called to tell her that his body had been recovered, she was completely unnerved. After some anguish, she decided Shaw’s ashes should be scattered in South Africa, the place he had come to love so much. Ann continues to live and work in Hong Kong. Every once in a while, when she has a problem with the computer, or needs help in the kitchen, she finds herself thinking, Why did you do this to me? Because now I have to do everything. But it’s not anger she feels, just loss. “He needed to dive, and I accepted that,” she says. “I wasn’t about to change him or to tie him down.”

Lisa Shaw, in a eulogy for her father, wrote, “I know having faced death before that my father was unafraid and was completely at peace with the prospect. I know and he knew that the Lord would be right there ready to take him on to new adventures. I am also at peace because he died doing something he loved; very few of us will ever get that privilege.” Steven Shaw, who is 23 and is studying for a master’s degree at the Melbourne College of Divinity, finds some solace that his father died helping others. “But now I’m feeling more just sad that Dad’s gone,” he says.

Shirley misses Shaw, too, and has a picture of himself with Shaw, peering out of a recompression chamber, on his computer’s screen saver. “Dave died exploring and trying to achieve something he wanted to do,” Shirley says. “That to me is better than dying in a car crash.” Still, every day Shirley thinks, Ah, I’ve got to tell Dave that—only to remember that he can’t.

Shaw is not far, though. On a beautiful evening in May, Don and Andre Shirley took a bottle of wine and a small wooden box to the summit of a mountain a short drive from their home. Below them, the rich, pungent grasslands of Mpumalanga swept all the way to the distant horizon, and the Komati River glinted in the golden light. Next to a wild fig tree, the couple raised their glasses in a quiet toast. As the sun dipped low, they opened the box and threw Shaw’s ashes into the air. The ashes hung for an instant, a cloud of a man. Then the African earth took them, and Dave Shaw was gone.

Washington, D.C.-based correspondent Tim Zimmermann is the author of The Race.