Faulty, old pipe caused PES refinery explosion, sending a bus-size piece of debris flying across Schuylkill

A federal investigation blames faulty, old pipe for the explosion and fire at the South Philly refinery. Hydrofluoric acid was released in the blast.

A video still shows the 38,000-pound vessel that flew across the Schuylkill River when the third explosion occurred at 4:22 a.m. (Credit: Global News)

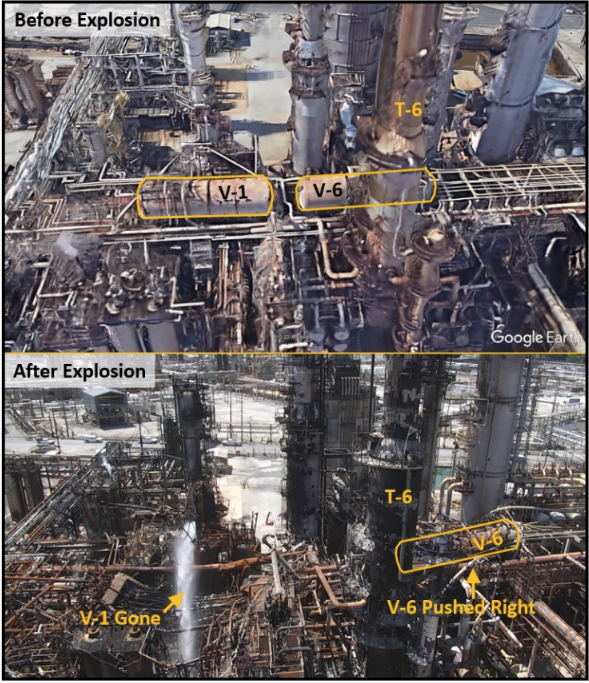

A piece of pipe, long overdue for replacement, spilled highly combustible hydrocarbons mixed with a dangerous chemical and caused the devastating explosions and fire at the Philadelphia Energy Solutions refinery in the early morning of June 21. One explosion sent a 38,000-pound vessel — about the same weight as a firetruck — across the Schuylkill River, where it landed on the waterway’s banks, near the company’s tank farm. PES estimates the incident released about 676,000 pounds of hydrocarbons, most of it — about 608,000 pounds — burned in the fire and explosions.

Those are some of the details in a report released Wednesday by the federal Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board. The report also says an estimated 3,271 pounds of the dangerous hydrofluoric acid was released into the atmosphere, while the refinery’s water spray system contained about 1,968 pounds of HF. The release of the chemical did not cause any injuries. City officials had previously reported they did not detect any HF escaping.

Hydrofluoric acid is one of the most deadly industrial chemicals in use. Integral to the creation of high-octane gasoline, it is used as a catalyst and has been combined with highly flammable hydrocarbons at about 48 alkylation units in the United States — including the now-closed South Philadelphia refinery.

Swallowing just a small amount of HF or getting small splashes on the skin can be fatal, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In a gaseous state, the CDC says, low levels of HF can irritate the eyes, nose and respiratory tract. Breathing it at high levels “can cause death from an irregular heartbeat or fluid buildup in the lungs.”

The Chemical Safety Board document provides previously unreported details of the explosions and fire that destroyed a critical part of the PES refinery, leading to a Chapter 11 bankruptcy and the layoffs of more than 1,000 workers. It also describes how the quick action of one employee helped avoid further catastrophe for workers and nearby residents.

At 4 a.m. on June 21, a large amount of propane, mixed with a smaller amount of hydrofluoric acid, leaked, forming a large ground-hugging vapor cloud visible on security camera footage. About two minutes later, the cloud ignited, causing a fire in the alkylation unit. The control room operator, Barbara McHugh, acted quickly and within 30 seconds activated the Rapid Acid Deinventory, or “RAD,” system, which transferred the majority of the deadly hydrofluoric acid from the alkylation unit to a tank far away from the fire. About 340,000 pounds of HF at the facility has since been neutralized.

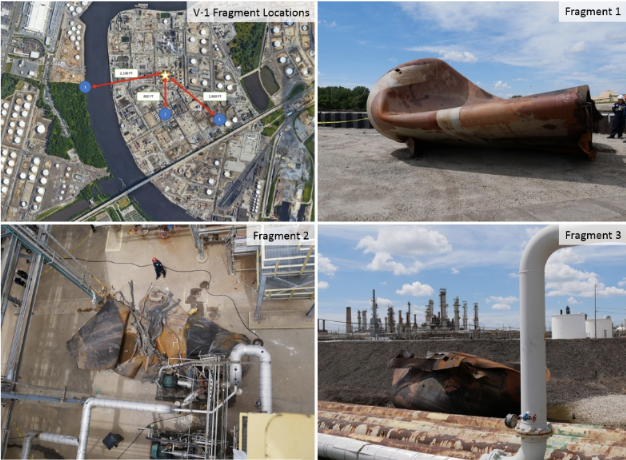

Three explosions occurred at the alkylation unit between 4:15 and 4:22 a.m., with the third and most violent rupture at a drum that contained butylene, isobutane, and butane. At least three fragments of the large vessel flew into the air, with the largest piece — at 19 tons about the same weight of a fully loaded Greyhound bus — landing across the Schuylkill River. A 23,000-pound fragment and a 15,500-pound fragment landed at the refinery. Just five workers were treated for minor injuries. The fire was extinguished at 8:30 the next morning.

“I’m impressed that industry had its act together, that it has a RAD system, and that they activated it in a timely fashion,” said Ron Koopman, a physicist and expert in chemical safety. “That’s new turf for industry taking responsibility. Because as far as I know … this is the best response that I’m aware of.”

As a senior scientist at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, where he worked for 36 years, Koopman conducted the definitive experiment on the release of hydrogen fluoride back in 1986. He said the HF that was released at PES was likely dispersed by the intense explosion.

“The explosion is nasty — it could kill people, but it’s not the principal hazard,” he said. “It’s the toxic gas [HF] that could continue to be toxic downwind. Sometimes, the explosion and the fire is your friend.”

Koopman’s experiment in 1986 released 1,000 gallons of HF at a Nevada test site. The results shocked him. A video of the experiment shows white billowing clouds of poisonous gas expanding and traveling rapidly across the desert. Highly toxic levels of HF were detected miles away.

Refineries typically have water spray mechanisms to contain HF, which were also activated at PES. Koopman said fast action is critical because once the HF is airborne, it can kill people at high concentrations.

“The [workers] are my heroes in this process,” he said.

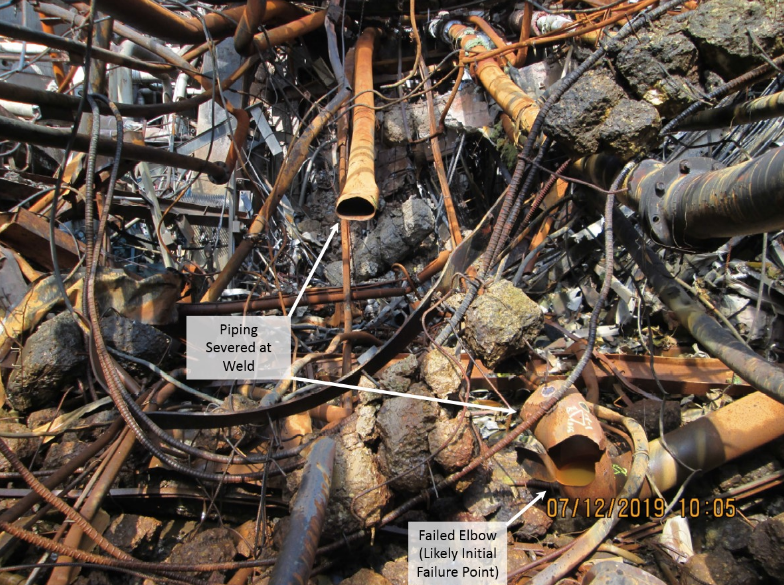

The June incident began when a 90-degree piece of pipe known as an “elbow” ruptured, releasing fluid containing hydrocarbons and HF. The pipes in the PES alkylation unit are monitored at specific spots — known as “condition monitoring locations,” or CMLs — to measure for thickness. The ruptured elbow, however, was not a CML, and thus its thickness had not been monitored.

PES had a policy that any pipe thinner than 0.18 inch would be replaced. The Chemical Safety Board’s investigation found that the ruptured pipe was only 0.012 inch thick — less than a tenth of the thickness that would have triggered a replacement.

John Jechura, professor of practice at the Colorado School of Mines, said deciding where to test is always a probability issue.

“You can’t check every square inch of pipe,” he said.

As a rule of thumb, he said, the areas most vulnerable to corrosion — and thus potential cracks and leaks — are places in the pipe where there is a change in the flow direction: T’s, Y’s, and elbows. Given that he was not involved with the PES plant, Jechura said he couldn’t say why the ruptured elbow was not an area that was monitored more closely.

Another issue was the pipe material. The pipes in the alkylation unit were installed in 1973, when industry standards did not specify how much nickel or copper they should contain. In 1995, however, those standards were updated, specifying that pipes should be no more than 0.4% each nickel and copper. The ruptured pipe contained 1.74% nickel and 0.84% copper.

Daniel Horowitz, a former managing director at the Chemical Safety Board (CSB), said explosions due to faulty, old equipment also occurred at the Tesoro refinery in Anacortes, Washington, in 2010 and at Chevron’s Richmond, California, refinery in 2012. He said current oversight is inadequate.

“The solution is to have a more advanced regulatory system, where more regulators have more resources and expertise,” said Horowitz. “Companies should be required to reduce risks to the lowest possible levels and use the most up-to-date standards.”

Petrochemical-industry standards are largely self-directed, and so any pipes installed before the regulations were updated in 1995 were grandfathered in, despite the fact that the American Petroleum Institute’s own recommended practice for “Safe Operation of Hydrofluoric Acid Alkylation Unit,” last updated in May 2013, states: “HF corrosion has been found to be strongly affected by steel composition and localized corrosion rates can be subtly affected by local chemistry differences.”

Mike Wilson, national director for occupational and environmental health at the BlueGreen Alliance, said that lack of oversight has meant refineries are not sufficiently required to invest in maintaining and improving safety.

“This is certainly the case with the federal standard for refinery safety, which is 27 years old and far outdated,” Wilson said. “It requires very little by refiners to actually fix process-safety hazards, such as corroded piping systems.”

Hydrofluoric acid is regulated by both the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

OSHA does so under the Process Safety Management of Highly Hazardous Chemicals. The EPA’s Risk Management Plan Rule governs public disclosures surrounding the use and accidental release of toxic chemicals, as well as emergency response.

The Obama administration had toughened those rules, but Trump’s EPA says it wants to roll back some of the new provisions, including the requirement that industry assess the use of safer alternatives.

However, other standards — like pipe maintenance and composition — are set by industry groups, and refineries generally police themselves.

According to the EPA, between 2007 and 2017, there were 1,517 reportable accidents at facilities using hazardous chemicals — nearly 150 incidents a year over 10 years. Nearly 500 of those accidents affected residents in surrounding communities.

“We don’t hear about them, but they’re significant enough to threaten people’s safety, if not their long-term health,” Wilson said.

He noted that in the explosion at Chevron’s Richmond, California, refinery, engineers had recommended on six different occasions that the company replace pipes that were out of date, but Chevron management decided not to replace them.

“The CSB continually points out that the most obvious causes of a major incident, such as a corroded pipe, are not what actually caused the incident,” Wilson said. “Major industrial failures like this are nearly always the consequence of management decision-making and the way safety is prioritized or not.”

Wilson noted that until the CSB report is complete, he couldn’t say whether Philadelphia Energy Solutions faced a similar issue with regard to safety culture.

Koopman, the physicist and chemical-safety expert, agreed that self-regulation may not be the best way to ensure that industry employs the best practices to keep workers and nearby residents safe.

“Luck has saved a lot of people in this business,” he said. “You would hope that we could do better than luck. But when it comes down to it, luck is a good thing.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.