Mass shootings, #MeToo, family separation, climate change, impeachment. The world is dark and getting darker. Or at least that's what it seems like from the relentless barrage of push alerts and Facebook posts blowing up our phones. In turn, we get angry, we despair, we withdraw. It's a vicious cycle, with seemingly no reprieve.

"We in the media—because of our own need for eyeballs and clicks and profits—we're not telling the healing stories," says author Irshad Manji, who is among the people Newsweek spoke to about how to move beyond fear and begin to fix our nation's problems. "We're telling the stories of the conflicts. We need to hear both."

BY BARACK OBAMA

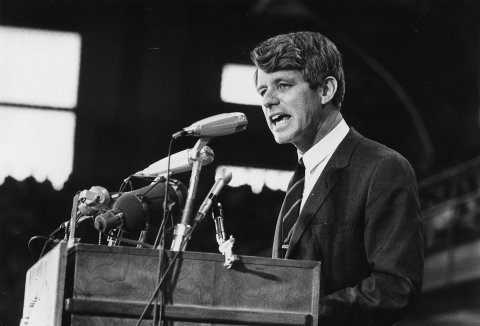

Robert F. Kennedy knew a thing or two about hope. Half a century ago, it was hope in the future, hope in people, hope in our capacity to do better, to be better, that spurred him to challenge a sitting president of his own party and challenge the conscience of a nation.

And through steel towns and crowded housing projects and windswept Native American reservations, Bobby reinvigorated an American spirit that was bruised and battered and still reeling from assassinations and riots and protests—and hatred. And he had ambition, and he had moral clarity. He argued for unity over division, for compassion over mutual suspicion, for justice over intolerance and inequality. And standing on some makeshift platform, maybe on the trunk of a convertible or the back of a flatbed, sometimes speaking into a tiny microphone while an aide held up a portable speaker, he felt authentic, and he felt true, not stage-managed or prepackaged like so many people in public life.

Which is why when you look at the photos and you look at the footage of that remarkable period, what sticks out is the sea of hands surrounding him seemingly everywhere he went. Dozens of hands, hundreds of hands, thousands, every shape and every color, the smooth hands of children and the wrinkled, worn hands of the elderly, and they're all reaching upward.

He understood that it wasn't blind optimism that he was peddling. Hope is never a willful ignorance to the hardships and cruelties that so many suffer or the enormous challenges that we face in mounting progress in this imperfect world…. [It's] a belief in goodness and human ingenuity and, maybe most of all, our ability to connect with each other and see each other in ourselves, and that if we summon our best selves, then maybe we can inspire others to do the same.

It's been 50 years since we lost Bobby, and because we still seem to be grappling with some of the same issues that he was in 1968, when I was 7 years old, because we are still dealing with poverty and inequality and racism and injustice and environmental degradation and a constant stream of senseless violence, because of all that, it can be tempting sometimes to succumb to the cynicism, the belief that hope is a fool's game for suckers. And worse, at a time when the media are splintered and our leaders seem content to make up whatever facts they consider expedient, a lot of people have come to doubt even the very notion of common ground, insisting that the best we can do is retreat into our respective corners, circle the wagons and then do battle with anybody who is not like ourselves.

Bobby Kennedy's life reminds us to reject such cynicism. He reminds us that because of the men and women that he helped inspire, because of the ripples that he sent out, because of the often-unrecognized efforts of union organizers and civil rights workers and peace activists and student leaders, things did in fact get better.

In the years since Bobby's death, tens of millions would be lifted out of poverty. Around the world, extreme poverty would be slashed, and more girls would begin to gain access to an education. Millions of Americans would be shielded by health insurance that wasn't available to them before. That progress is fueled—by hope. It's not fueled by fear. It's not fueled by cynicism. And this is maybe the most important thing: It's not dependent on one charismatic leader but, instead, depends on the steady efforts of dreamers and doers from every walk of life, who fight the good fight each and every day even when they're not noticed.

Six years ago, Lucy McBath's son was shot and killed in the parking lot of a gas station because the kids in the car were playing music too loud, apparently, and she turned her grief into hope and her hope into a seat in the next Congress, running unabashedly against the gun lobby in the great state of Georgia. She won.

And then there are the Parkland students. It hasn't even been a year since a mass shooting stole 17 lives at their school, but less than a month later those students had helped to raise the age to buy a rifle in Florida. They'd lengthened waiting periods before purchase. A couple of weeks after that, they'd inspired hundreds of thousands to march in the nation's capital and all across the country. And, of course, they haven't won every battle, but online, in the media, in the streets, on college campuses, they have become some of our most eloquent, effective voices against gun violence. And they are just getting started. Who knows what they're going to do once they can actually rent a car?

Ripples of hope. That's the legacy, that's the spirit, that Bobby Kennedy captured, standing on top of a beat-up car 50 years ago. Those are the descendants of the men and women and children who reached up into the sky, trying to get a touch of hope.

The 44th president of the United States, Obama was awarded the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Ripple of Hope Award on December 12. This is an excerpt from his speech, shared with Newsweek.

BY STACEY ABRAMS

I believe in asking three questions before moving forward: What do I want? Why do I want it? And how do I get it? My primary goal is to eradicate poverty; I believe it is immoral and a stain on our society. And so when I despair or get angry, I take the time to think about how I can best achieve that goal—and then I get to work.

As a writer and former elected official, I believe in the power of words. We must use words to uplift and include. We can use our words to fight back against oppression and hate. But we must also channel our words into action. We must lobby our leaders, cast our ballots and advocate for real change in 2019.

Discriminatory legislation emboldens those who seek to make us afraid, while giving those communities it hurts a concrete reason to fear. We must stay away from anti-immigrant legislation, as well as so-called religious freedom legislation that harms our LGBTQ communities. Inaction discriminates too. In Georgia, our refusal to expand Medicaid has caused undue harm to our rural Georgians, people of color and women.

Too often, our fear is sowed from an idea that our diversity is a weapon or a weakness. We must instead realize that our diversity is our strength; it allows America to be the rich and enterprising nation we are.

When speaking to someone who is afraid, try to find common ground on which you can build hope. As Democratic leader of Georgia's General Assembly, I worked with the Tea Party on environmental legislation—so I know you can find common ground with anyone.

Abrams lost a close race for Georgia governor in 2018. She would have been the first black woman elected governor anywhere in the United States. She is Google's most-searched politician of 2018.

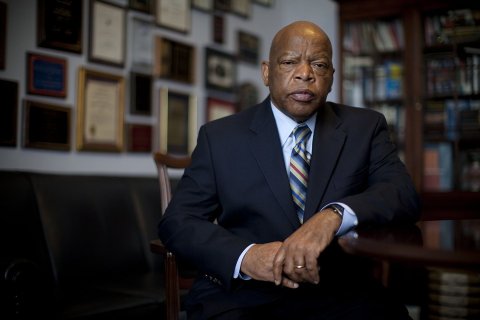

BY JOE KENNEDY III

I wish it were easy to change human nature. Fear motivates, but hope does too. One person who regularly activates that idea is John Lewis, representative for Georgia, our most optimistic member of Congress. There is not an elected official who has been let down more often by people than he has—people who should know better and have his best interests at heart. He's been arrested over 40 times and beaten and nearly killed. Yet he has lived, seen, fought and bled for the ability of the United States to change and become a more perfect union. There is value in that fight and pursuit.

Lewis was at a memorial service for the Mother Emanuel church shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, listening to family members who had lost loved ones speak, and he got up and talked about forgiveness. He said that our nation had learned to forgive, and he told a story about how, when he was 21, he was beaten by Ku Klux Klan members in South Carolina. Years later, a man came into his congressional office with his son and asked for him. He said that he was one of the members of the Klan who had beaten him, and that he had come with his child to apologize. They hugged, and both cried.

To continue to get up and fight and to always say, "Hello, brother," the way he does, shows that we are human, we are fallible and we make mistakes. We have the capacity to resist fear and be strong. We as individuals have a choice to make, and our country's history shows that in those real times of crisis, we do try to be big and bold. When our Founding Fathers wrote that all men were equal, they meant rich, white Protestant men. We have worked to expand that. To help people like the poor migrants who come here seeking a better life, as my family did when we first got here.

When faced with someone speaking out of fear, call it out. Speak up. Ask the fundamental question, "Why do you feel that way?" Listen to those answers to expose the fallacy of their argument, so that you can address that underlying fear. If people are willing to have an honest conversation around, say, immigration, they might say, "We can't afford it," or "It's going to displace us." Those are statements you can engage in. Be tenacious enough to not let the argument die.

Countering alternative realities with facts is hard. But it isn't any harder than it was for African-Americans in the civil rights movement or for the women who fought for suffrage.

The grandson of Robert F. Kennedy is a lawyer and has been the U.S. representative for Massachusetts's 4th Congressional District since 2013.

BY JUDITH JAMISON

One of the most beautiful things about art—and dance specifically—is that it brings people from all backgrounds, races and religions together. Alvin Ailey said, "Dance came to the people and should be given back to the people." Ailey gave us works of timelessness and energy that hit you at a core level, in your soul, no matter where you're coming from in the world, what language you speak or what political party you are with. At a time where there's so much tension surrounding race, gender and politics, it's important to have places where people can feel united in an experience that might not be their own. People who did not grow up understanding African-American hymns, rituals and baptisms, or what it meant to grow up in the South, can see a completely different perspective. And for those who lived that history, it's a full-circle moment.

In 1960, Ailey created a piece called "Revelations," which the company has continued to perform ever since. It's based on his blood memories, of growing up in the segregated South. At that time, the church was the hallmark of civilization for black people. The choreography in "Revelations" shows our humanity, that we are human, that we experience joy and pain. It's triumphant too—no matter what you throw at African-Americans, we tackle it. We persevere. And that is a story everybody can relate to. (Excerpted from an interview with Janice Williams.)

Jamison is a dancer and choreographer who was director (1989 to 2011) and is now artistic director emerita of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2018.

BY RUSSELL MOORE

The fear that seems to toxify our cultural ecosystem right now seems to be less about danger from an external threat and more about the terror of being "exiled" from one's own "tribe." That's the reason people are retreating into their ideological silos. No one wants to be accused of talking to "the enemy," whether that's on social media or in the highest levels of government around the world.

Courage is grounded, in my view, in a sense of confidence and of personal identity that transcends what we see around us in this toxic time. That sense of identity is what propelled the Apostle Paul to overcome fear of everything from mob violence to execution by the authorities as he carried the gospel around the known world of the time. "For am I now seeking the approval of man, or of God?" he wrote. "If I were still trying to please man, I would not be a servant of Christ" (Galatians 1:10).

We see the example constantly, whether in the Bible or in world history: The way to overcoming fear is for men and women of conviction to take a longer-term view than the present moment. Roger Williams [the Puritan theologian who founded Rhode Island] must walk out into the wilderness alone, for the sake of future communities living in freedom. A sense of loneliness now is often the key to flourishing community later.

Moore is president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, the public policy arm of the Southern Baptist Convention.

BY IRSHAD MANJI

True story: A young hip-hop artist from Biloxi, Mississippi, wants the stars and bars in her state flag replaced by an inclusive and unifying design. She invites a supporter of the Confederate battle flag to her home, where they discuss his perspective. Soon after, he realizes that he cares more about defending her dignity than about preserving a symbol. He then stops flying his own Confederate battle flag. What sparked the transformation? Respect. The activist respected the flag-waver enough to engage rather than label him.

The word respect comes from the Latin word meaning to turn around and look again—to re-spectate. If I see people only as the labels that I affix to them, then I'm not taking the time to look again. By looking again, I'm saying, "You have a backstory that I don't yet know. Will you share it?" And by going first in the listening department, I set the tone, the culture of the conversation. That puts me in the driver's seat rather than in the victim's position.

Over the past two years, more and more of us have found ourselves saying, "Don't label me." Don't assume you know me just because you think I fit this or that category. Let's be honest: Labeling is a game, a way of scoring points by putting people in "their place." It's manipulative, demeaning and ultimately enraging.

On social media, humiliation happens at warp speed. Each tribe believes it's being labeled, but the side that feels victimized is doing the exact same thing to the other side! Clearly, nothing will change—not cultures, not systems, not institutions—until we the people change. And since labels aren't going away, we ought to treat them as starting points rather than finish lines.

Starting points for what? For asking each other questions in the name of respect.

Here's a courageous exercise that more of us could turn into a concrete habit: When you're being disagreed with, ask not how you can change the other person's mind; ask what you're missing about the other person. Most young people aren't being taught this lesson: that if you want to be heard, you first have to be willing to hear the other person. And appreciating that is key to a lifetime of success. Sincere relationships make for social progress that endures.

The future's more uncertain than ever—politically, technologically, economically. But, thanks to human psychology, you can predict what moves your opponents to cooperate with you. Step one: Replace labeling with listening.

Manji is an Oprah "Chutzpah" award winner, founder of the Moral Courage Academy and the best-selling author of the upcoming Don't Label Me: An Incredible Conversation for Divided Times (St. Martin's Press, February 26).

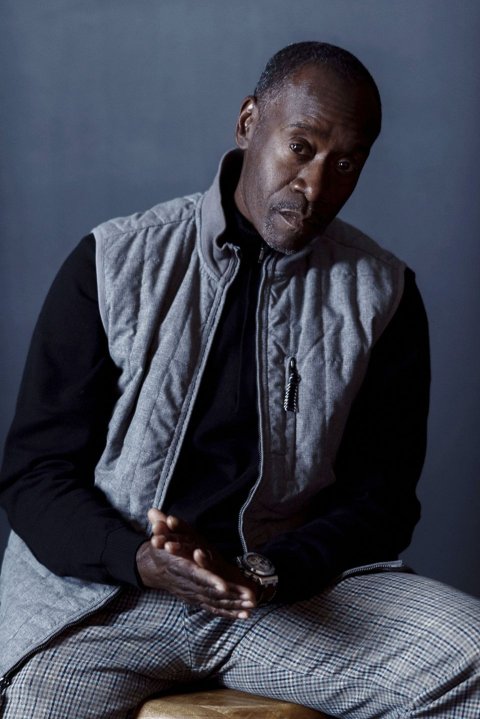

DON CHEADLE

Fear is the thing that helps us get from rock to rock and not be eaten by the scary thing. Fear is hardwired into us and will never not be. But we have a hard time distinguishing between different kinds of fear. The fear of not being accepted, for example. We don't think that; our body feels it at a DNA level, in the same way as "I'm going to be eaten." Fight or flight is triggered immediately, and it takes critical thinking to go, "Wait a minute, I'm not about to be eaten right now. I'm being challenged on a perspective or idea that I have. Someone is being critical of my work."

The mentality of "I have to stand my ground, and I have to not back down"—that's a fear-fueled idea. Our leader right now, "Individual 1," is all about that: "I cannot be pushed back off of my perspective—that makes me weak!" He is a master at leaning into fear, exploiting it, whipping it up. And most people aren't adept at understanding how to deal with that and still move forward.

That December 11 press conference with Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer [in the Oval Office]? You saw that attitude on display, but you also saw how not to succumb to it. Individual 1 said to Schumer that "Nancy Pelosi's having a hard time talking right now." Pelosi was like, "You don't have to talk around me. I'm sitting right here! Do not characterize my strength as something else." I thought that was very important, because she demonstrated how you can confront an attitude fueled by fear.

But it takes practice. Most people don't like conflict; it's fight or flight, and you react in one of two ways. Few people can sit there and deal with it. So we need to invest in diplomacy and crisis management. We should have an empathy class in school, teaching kids how to listen, how to take it in and not just be on your heels about everything.

Actors do this all the time. We're always thinking, How does someone else feel? How would I feel if I were in that position? We're forced to do introspective things. Most people are just trying to get from day to day, to get to Friday, to get their check and then go watch something to take their mind off this stuff. Finding the peace to not always be governed by your reflexes takes work and concentration.

I don't know that I have the answer for how people can do better at that. Getting off social media helps, particularly if you're thin-skinned! I don't leave Twitter stressed out and wanting to go punch somebody in the face, because if someone calls me a dickhead, we have a discourse. It's tai chi: If you don't attack back, pretty soon [the name-calling] is over, and now you're talking about whatever started the debate. Then that person has moved from their reflexes back into their brain. (Excerpted from an interview with Anna Menta.)

Cheadle and fellow actor George Clooney were presented with the Summit Peace Award by the Nobel Peace Prize laureates in 2007 for their work to stop genocide in Darfur.

BY BEN SHAPIRO

The divisions we see in America—that seething partisan hatred we've come to expect in our politics—didn't emerge from nowhere. It began during the Obama administration; President Donald Trump's election was merely a symptom of those divisions. There's no question that Trump's overheated rhetoric and trollish nature have exacerbated pre-existing divisions. But we need to understand that those divisions run far deeper: He could disappear tomorrow, and the social fabric will remain torn.

There's been a lot of talk recently about the necessity of getting outside our social bubbles and dealing with each other in person, on a human level. But social connections can only be effective when supported by a common moral framework. Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam points out that diversity in communities doesn't tend to build social fabric unless there are common values; he gives the examples of churches and the military. But even our most basic values are now divided. Free speech? Many on the intersectional left believe that it is a reimposition of an unjust hierarchy. A commitment to limited government? Half the country, at least, wants a far larger government. Even the belief that we live in a free country in which you are capable of changing your life is a controversial proposition these days.

In 2013, President Barack Obama stated in his second inaugural that "being true to our founding documents does not require us to agree on every contour of life. It does not mean we all define liberty in exactly the same way or follow the same precise path to happiness." That may be true on the margins, but we must agree on what liberty constitutes if we hope to be united under its banner.

Shapiro is a political commentator, writer, lawyer and host of the podcast The Ben Shapiro Show.

BY JILL LEPORE

It appears to me that the U.S. entered a period of political disequilibrium around 9/11. It had to do, of course, with the violence and terror of that moment, the agony of the loss. But that moment happened to coincide with the rise of an awful lot of disruptive technology. In this new era, politicians mobilized and heightened fear in order to manufacture political support for wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. But people got worried about technological disruption all on their own, because it knocked most of us back on our heels.

Meanwhile, over those same few decades, a lot of sources of assurance dissipated. Think of the universal audience for FDR's telling Americans, "The only thing we have to fear is fear itself"—everybody heard that. It gave him an authority that we might have a jaundiced view about today, but that was an extraordinarily effective message in a very dark time. Where does that authority now lie? If you think about the places that people go to reset, to regain equilibrium after a terrible event, they've gotten scarcer and scarcer. Nostalgia is no measure of anything, but I can't help but remember the Sunday sermons I heard as a kid, during the Cold War, listening to the parish priest say something wise, an experience that was not unlike the feeling I got watching Walter Cronkite on television, or reading essays or poetry by people wiser still, and bolder.

For better or worse, those sources of authority, people in a position to assure us, don't exist for many people anymore, which wouldn't be a problem, except that it's not clear to me that new sources have risen in their place. The Catholic Church that provided me with childhood solace was the same church that destroyed other children's lives. National politicians, constantly campaigning, find it expedient to keep pouring accelerant on the flames. Critics of TV news complained about what ratings did to journalism. But a journalism driven by algorithms turns out to be a lot worse than one driven by ratings. Keeping people afraid is in the narrow, shortsighted, political and financial interest of a lot of people.

Is the terror worse? I don't think so. Mass shootings, including attacks on places of worship, like the Pittsburgh temple and the Charleston church, are devastating, but those reigns of terror, however devastating, are not new. Lynchings, bombings of churches and temples—we have been through this before. The courage of people who fought against those forms of terror is one of the great stories of the 20th century. You see the same thing in Pittsburgh and Charleston and Parkland: this litany of grief, these monuments of fortitude and endurance.

So who is holding everyone together? At public schools all over the country, not many weeks pass before yet another email from the superintendent about a swastika in the bathroom, or a bomb threat, or a lockdown. Then the community meets, and it's a beautiful thing. People say, "We're not going to be afraid of this. Let's have the bake sale that we were going to have tomorrow anyway."

The rabbi at the synagogue, the school principal, the mothers at the bake sale—these are not elected people. They're not interested in votes, or clicks, or likes. It's not in their interest to keep people afraid. So if you want to find hope, think about the exhausting work that teachers do every day, helping kids make sense of this very brutal world. You're 9 years old, and you already know about climate change. Your cousin in Texas has suffered through a hurricane. Your mother's friend lost a house to California wildfires. You have lockdown drills at school once a month, because there are strangers who would like to kill you. What do you tell that child? You tell that child about love and knowledge and courage and history.

Lepore, a professor of American history at Harvard University, is the author of 2018's These Truths: A History of the United States (W.W. Norton & Co.).

BY NICK CAVE

I made my first soundsuit in response to the brutal beating of the unarmed Rodney King by officers of the Los Angeles Police Department in 1991. I remember being afraid. I thought that my identity was only protected in the privacy of my own home, that the moment I left that space, I would be just another profile. So I made this suit of twigs and debris—a sort of body armor that erased gender, race and class, that rustled when I danced. Since then, I've made over 500 soundsuits and feature them in live performances. What I see is that people wearing them become like shamans. Traditionally, shamans find the information that allows you to grow and heal, and when you're wearing a suit, or watching a performer dance in a suit, you are transformed by joy and a sense of shared humanity—the opposite of fear. It's impossible not to love thy neighbor when you're dancing with them! (Excerpted from an interview with Mary Kaye Schilling.)

The American fabric sculptor, dancer and performance artist's Soundsuits have been collected by museums around the world.

BRYAN STEVENSON

I deal with people all the time who have been acculturated to hate, and when something complicates that, they don't know what to do. If you extend a hand, many of them will grab it because hating is exhausting. It's miserable and demoralizing, and it makes you depressed. Some people are just not ready to engage, but I never rule out the possibility of having those people hopefully see something they haven't seen before.

Parents learn that when they're really angry with their kids, that's not the time to react or discipline them. And the same is true of fear. It will cause you to do all kinds of irrational things. So if we want to be rational, if we want to be thoughtful and strategic and compassionate, we're going to have to push back against the politics of fear and anger. Once you have a consciousness about it, you hear it. So when you listen to a political speech, and what the candidate is saying is "Be afraid and be angry," then you want to ask yourself, Why is that the prescription I'm being given?

Part of understanding history is that you'll see that it was fear that generated the most shameful and destructive abuses of our past, like the genocide of Native Americans, slavery, lynching and segregation. The placement of Japanese-Americans in concentration camps was based on an irrational fear and anger. But what we did was unjust, un-American and unconstitutional. And it was racist: We didn't have the same response to German-Americans or Italian-Americans. Understanding that can temper what we should think on issues like immigration or education.

So when you hear someone say, "Those people, they're nothing but animals. Those people are rapists," you begin to think, Wait a minute! We don't talk like that. That's not a pathway to responsible government. When you do that, politicians can't talk that way with an expectation of reward. We're at a moment where there is a rise of the politics of fear as a pathway to power. It's also a pathway to oppression and injustice and inequality. And those are the things that have to compel us to resist them. (Excerpted from an interview with Mary Kaye Schilling.)

Stevenson is the founder of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative. In April, EJI opened Montgomery,Alabama's National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which remembers the thousands of black men, women and children lynched in the United States.

BY JOHN KERRY

Things only change when people make them change. Citizenship isn't passive; it's active. I spent two years fighting to end the war in Vietnam. I got arrested in an act of civil disobedience with hundreds of other vets. People screamed at us, "Support the troops," and we'd respond, "We are the troops." Know what happened? Richard Nixon won 49 states in 1972, and I learned the president waited up until news confirmed that I'd lost my race in Massachusetts before going to bed.

I became an optimist the hard way. I got knocked down, but then I got up. Not even two years later, Nixon had to resign, and a new Congress of reformers came to Washington to end the war and clean up the corruption. But it didn't "just happen." It never does. You have to get in the arena.

There are many examples of people who put themselves in the arena. Remember Michael Jordan's rule that he didn't do politics because "Republicans buy sneakers too"? Bruce Springsteen put his name and reputation on the line by speaking out in his own way about America and our elections. Carole King lives the word citizen. She's on Capitol Hill every year fighting to preserve the Rocky Mountain Northwest.

In 2002, I got to know an activist in New Hampshire. Her son was in a wheelchair, and she became a fierce advocate for special education funding. She worked her butt off on my campaign. We lost, but she didn't give up. She's Maggie Hassan, and now she's a U.S. senator fighting for millions of kids, the same way she did for her own, arguing at school boards. That's what you do. You fight. You keep pushing.

I don't believe we have to be captives of demagogues, and if I were a citizen in a state and all I heard was the vilifying, name-calling and the hyperventilating headlines, I could understand why people tune out or worse.

But you have to listen. Thirty-two years ago, assigned seating put me face to face with a guy who had opposite views about a war in which we'd both served. We didn't trust each other. We didn't really know each other. But after a long conversation on a long flight, we decided to work hand in hand to make peace with Vietnam and with ourselves here in America. I will never forget standing with John McCain, the two of us alone, in the very cell in the Hanoi Hilton where years of his life were lived out in pain but always in honor.

One thing the service and the Senate taught John and me—at some point, America's got to come together. If Washington is a city where you can bridge the divide between a protester and a POW, finding common ground on anything else shouldn't be hard at all. But you have to force open a dialogue. And you have to listen.

Kerry is a former U.S. senator from Massachusetts; he served as secretary of state under President Barack Obama from 2013 to 2017 and is the author of Every Day Is Extra (Simon & Schuster), which came out in September.