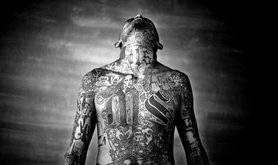

Members of Mara Salvatrucha listen to a mass in Ciudad Barrios, San Salvador, El Salvador. Edgar Romero/DPA/PA Images,. Todos los derechos reservados.

Leaving behind the cacophony of car exhausts in “Great San Salvador”, the high-sounding name our driver uses to refer to the metropolitan area of El Salvador’s capital city, we head towards a neighborhood on the outskirts controlled by the Mara Salvatrucha, also known as the MS-13 gang.

As part of the field research for an International Crisis Group report on security policies in El Salvador, the aim of our visit is to find out first-hand what day-to-day life is like in a gang-controlled area and what the people who live here are most concerned about.

The conditions in which they live are shared by a majority of Salvadorans, given that criminal groups are established in more than half of the country’s 262 municipalities, according to conservative estimates.

As a precautionary measure, we have been advised to wear casual clothes and avoid letters or numbers, especially thirteen and eighteen, which refer to the largest gangs in the country: the MS-13, the 18-Sureños and the 18-Revolucionarios.

A few miles away from our destination, the colleague who has helped arrange our visit gives us a last-minute warning: "If anything happens, let me do the talking. And, above all, never try to look them in the eyes".

As a precautionary measure, we have been advised to wear casual clothes and avoid letters or numbers, especially thirteen and eighteen, which refer to the largest gangs in the country.

We take a detour from the main road to get to the community we are to visit. Through our van’s unpolarized windows we soon see it. The atmosphere is amazingly calm. It is about four o'clock in the afternoon, and a caravan of uniformed schoolboys is making its way home along the edge of the road under the cool shade provided by the extremely thick trees.

Our van bumps to the end of the unpaved road and the silhouettes of a group of young people come into view. Some of them are wearing caps and have no t-shirts on, while some stand and others sit at what appears to be an improvised roadblock.

We slow down, lower the windows, and one of the community leaders who is with us extends his arm to greet the MS-13 soldiers, one of the lowest ranks in the gang hierarchy.

They indicate with a gesture that we can keep going. I watch the scene out of the corner of my eye, trying not to lose sight of the road ahead while concealing the artificial expression of tranquility on my face. We then reach our destination.

Most communities in El Salvador, even the most humble, usually maintain a locked access gate that only tenants possess a key to. The community we are visiting even has a 24-hour surveillance system manned by neighbourhood men who take turns to stand guard.

It seems unavoidable to ask why they have so many security measures in such a remote, seemingly quiet place. But we wait for the neighbours to tell us about it as we begin talking about the community’s daily life.

Neighbourhoods such as these have become the main focus of conflict between security forces and gang members in recent years. Between January 2015 and August 2016, El Salvador’s National Civil Police (PNC) recorded 1,074 armed clashes.

After winning the 2014 elections, the new government put an end to the previous truce policy promoted by Sánchez Cerén’s predecessor Mauricio Funes.

A new version of the “iron fist” policy which has been used by every government in El Salvador since 2003 is a pillar of current President Salvador Sánchez Cerén’s security strategy. Sánchez Cerén is a former guerrilla from the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), which is today a political party.

After winning the 2014 elections, the new government put an end to the previous truce policy promoted by Sánchez Cerén’s predecessor Mauricio Funes, also from the FMLN. Between 2012 and 2013, Funes sought to reduce the number of homicides in exchange for prison benefits.

The increase in anti-gang operations in the communities in recent years has been complemented with a series of extraordinary measures in a number of prisons where gang members remain in isolation and in deplorable conditions.

An ambitious prevention strategy called El Salvador’s Safe Plan, although incorporating rehabilitation as one of its five axes, has so far been implemented focusing almost exclusively on fighting crime.

"How is it with the gangs here? Do they leave you alone?", I ask a male resident during our conversation. He approaches and opens his eyes wide. "They", he whispers, as if they could hear us, "they are not the problem. If we don’t do anything to them, they leave us alone. But the police, they sure are a problem".

One of my colleagues joins the conversation and explains that a few months ago a mixed force from the police and military – the hybrid formula that has now become the norm in all anti-gang operations in El Salvador – abused him right at the entrance of the community. "They even pointed a gun at me. It was very unpleasant", he says.

Given the large number of policemen who live in gang-controlled areas, many of them have to remain hidden in their neighbourhoods or move away to safeguard their lives.

Although the Salvadoran PNC (National Civil Police) is one of the more popular police forces in Central America, the pressures and the cycle of revenge between gang members and police have skyrocketed since the end of the truce and the implementation of the new security strategy. In 2017 alone, gang violence killed a total of 66 security officers.

Given the large number of policemen who live in gang-controlled areas, many of them have to remain hidden in their neighbourhoods or move away to safeguard their lives. They have become the target of those who are attacking the state for its increased repression.

"So, you go and talk to [the gangs] without any problem?" I ask. "Yes, we do. When there is a problem, we meet with them and fix it. They know us, we are all from here", says the community leader we are interviewing.

Despite the fact that gangs have been considered terrorist groups since 2015 by El Salvador’s Supreme Court of Justice, the reality in communities such as these is very much the same throughout the country. Dialogue with gang members, who are considered by the State itself de facto authorities in many areas, is part of everyday life for thousands of Salvadorans.

"I must tell you, though," says our interviewee, "those guys, what they need is a job. If they were given a job, there would be no more crime".

The community leader tells us about a personal experience of his with the local gang members.

Weighed down by the high level of crime and the shortcomings of its productive sector, the country's economy is essentially outsourced and 16% of its GDP comes from remittances from the United States.

When labour was needed to build new housing in the neighbourhood, he hired the youngsters manning the block down the road. He told us that when the building work was finished, the patojos, as the Salvadorans call young people, went back to their usual behaviour.

This community leader’s story is a reflection of the hard economic reality across El Salvador, the country with the lowest economic growth in Central America. Weighed down by the high level of crime and the shortcomings of its productive sector, the country's economy is essentially outsourced and 16% of its GDP comes from remittances from the United States.

Call centers, where many deported people from the United States who are proficient in English end up working, have become the country’s great hope for job creation. In El Salvador, one in five people between the ages of 15 and 24 years do not study or work.

Our hosts warn us that it is safer for us to get going before sunset. We bid them farewell with a strong handshake and promise to be back with a copy of our report when its published.

We start the van and drive out of the community towards the MS-13 improvised roadblock. Once more, we slow down as we approach and lower the windows.

Although I try to be strong and keep looking ahead, I cannot help but divert my gaze to sneak a glance at them. I want to see who are the individuals posing the threat I just heard about in whispers, the people who are forcing more than half of the country to its knees and to whom even the President of the United States dedicates a disproportionate segment of his public speech.

What I saw was a tall, dark, shirtless boy, no more than 16 years old, with a shovel resting on his shoulder and a hand on his hip. He had a proud look on his face.

He appeared like an apprentice labourer pausing before going back to his toil. When he outstretched his hand towards the van, I asked our colleague if he wanted something. "They ask for a little help, because they are patching up the road. Sometimes we give them something, but today I don’t have any coins with me", my colleague explained.

I wondered what time has in store for these young MS-13 soldiers, without resources and with a guaranteed future in prison or death.

When we reached the main road, the words of the community leader kept ringing in my ears: "Those guys, what they need is a job. If they were given a job, there would be no more crime". I wondered what time has in store for these young MS-13 soldiers, without resources and with a guaranteed future in prison or death.

Probably, at some stage when they grow older, they may want to leave the gang, as a recent survey of more than 1.000 imprisoned gang members by the International University of Florida indicates. They will then have to try to produce family obligations or become active members of an Evangelical church, which are the only two recognized ways to "calm down" or leave the gang.

Night falls in “Great San Salvador”. As we drive further away from the community, I think of the neighbours we talked to, the MS-13 worker-soldiers and the policemen who mistreated our colleague.

They are all Salvadorans, humble and poor and they have a similar uncertain future that any security policy, however good it may be, is doubtful to improve.

El Salvador’s prospects can only be improved by a profound change in the country’s economic model, a policy of victim assistance that does not criminalise people for where they live and, above all, engagement in community dialogue with those who want to leave behind a criminal life.

In the meantime, violence in El Salvador will continue to live with a sense of injustice which, as Monseñor Óscar Romero insightfully said, "is like a snake, it only bites those who go barefoot".

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.