The email I sent to my editor was deceptively simple: "I've been reading a lot of articles about being more productive, cooking better, consuming more news, reading more hot takes, doing it all. I was wondering what would happen if I just... didn't..."

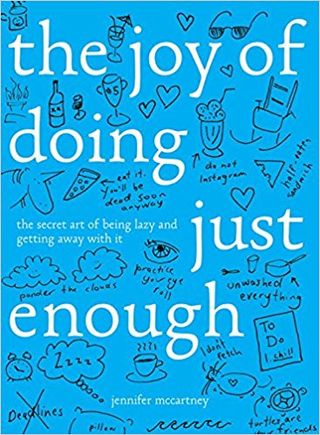

It was an idea that was inspired by Jennifer McCartney's new book The Joy of Doing Just Enough (out April 3). An advance copy had arrived in the mail addressed to me like a very pointed message from the universe. In the slim, funny tome, McCartney extolls the virtues of mediocrity and the health and well-being that can come from not trying so hard. I was sold. My editor was, as well.

The subtitle of the McCartney's book is The Secret Art of Being Lazy and Getting Away With It, something some might say I cleverly omitted from my initial email. I'd argue I didn't omit it; it's a secret art, so...

The point is, as McCartney notes, there's a relentless cultural drive to excel at work and keep a clean, on-trend home and eat well and maintain a bustling social life. Plus, one should also find the time to binge hours of Quality Television every week, listen to an ever-growing slate of engrossing podcasts, explore a myriad of fitness journeys, and keep up with the news whilst also pretty much constantly protesting because of said news. I didn't know where to start, so I took the arrival of McCartney's book as the universe's way of saying: don't start anywhere. Just stop. Literally don't. Who am I to argue with the universe?

The Joy of Doing Just Enough is a punchy de-motivational book filled with lists the author doesn't deign to finish, sketchy illustrations, and sharp-tongued real talk about achievement. "The idea that we need to be constantly productive and operating at 100 percent is just some capitalist bullshit we've been conditioned to believe in by society," she writes. "Unless you live in France, of course, where the government gives you five months of vacation and you get paid in cases of Syrah." I do not currently live in France, unfortunately, so I decided to try plan B.

For the purposes of this assignment, I broke my life into three categories: Home, Work, and General Well-Being. McCartney drills down a little more, with chapters dedicated to relationships, social life, arts and culture, and health and beauty. I got overwhelmed and decided to just lump them all together and wing it. I feel like McCartney would approve.

Home

McCartney uses a three-step method to outline how to do just enough and the second step, "Indifference is essential," provided a template and a challenge for my home life. "Our brilliant ancestors invented frozen and canned foods... and the results were glorious," she writes. I threw the book across the room. I'm not Top Chef, but somehow I had come to believe that if I didn't use fresh fruits and veggies, herbs I chopped myself (and hopefully grew) and a complex recipe that I vetted by reading every review in the comment section, I would probably die. This is not true, apparently. I'm definitely also that person who finds himself stymied by a Blue Apron meal and orders Domino's. I contain multitudes—and buffalo wings.

On my weekly trip to the market, I asked myself what would happen if I made choices that prioritized ease and convenience over cuisine. Nervously, I Googled "easy weeknight recipe;" somewhere Nigella glowered. I found a salad recipe from which everything could come in a can and a roasted chicken recipe that was basically like, "throw your chicken in the pan, wait a while, take it out of the pan." I have to admit, I don't think I mastered the indifference part. Yeah, the chicken was easy to make but I definitely felt like I could be having a more delicious experience. The salad was fine but uninspiring. I wasn't hungry but was I full? Later in the week, we ordered pizza instead of stressing ourselves out over holiday dinner. That was, as McCartney says, "satisficient," but did I feel better? Meh.

I began to wonder if I should work harder at doing just enough. I was already failing this thing.

Work

Well, first of all, last Monday, news broke that Sanaa Lathan bit Beyonce, "ALLEGEDLY," and that threw my whole laziness plan out the window. I couldn't just not write about the biggest story of our time. I was trying to win a Pulitzer. But, I couldn't help but wonder, do lazy people want to win Pulitzers? (Also, do they give Pulitzers to GIF-filled articles about celebrity gossip? And if not, why not?)

McCartney's work chapter contains a lot of great practical advice about taxes, looking busy, and email (she suggests writing your emails at night and then setting them send at 6 a.m. so that people think you're on top of your game). But the point that I kept coming back to is her admonition to forget ambition. "I've been thinking about it," I mused to my husband over a lackluster un-fresh salad, "I'm just too ambitious. That and my wonderful personality are two are my greatest liabilities."

"Okay," he said.

The Joy of Doing Just Enough cautions "deadline are just suggestions." Later it reminds you, "You're a small cog in the machine of life. The machine needs cogs." I'd read these and reply "Yes, but..." like someone who hasn't quite gotten the hang of improv comedy. Doing just enough at work seemed to require rejecting the central agreements of most spaces, namely that work is necessary, that you should always want to do it better, and that it is your priority. I didn't know if I was ready for all that. This article isn't titled "I Spent a Week Dabbling in Anarchy and Whatnot." (That's next week.)

McCartney cites a Harvard Business Review study that showed an office was more productive when its employees were required to take breaks and barred from working late or working on weekends. I work remotely so the question of what working late or what a weekend is is rather debatable. But I did try to commit myself to not jumping into the Slack until a certain time in the morning and making plans at a certain point in the evening so I had to ostensibly step away. Of course, I spent most of my time being anxious about not being on Slack.

As I looked back at my work week in preparation for writing this article at the beginning of another work week, I realized I had totally failed this portion of my Just Enough experiment. I had been utterly extraordinary in all my professional endeavors. Unfortunately.

Everything Else

McCartney's third step in her Method hit me the hardest. "Being busy is bullshit," she writes. "Being busy is for idiots." I looked at my overfull calendar, my long Netflix queue, my unread texts, and the multiple to-do lists, some of which include the item "finish to-do list," and thought, "I might be a little bit of an idiot."

The book makes wild suggestions like waking up when you feel like it or just showing up to dinner parties even if you haven't bought a card or a bottle of wine. I literally have a basket of greeting cards and a spare wine rack so I never have to experience this. But maybe that's not the point. A gleeful nihilism takes over the later chapters of the book as it breezes through romance, social obligations, and health. "A good thing to keep in mind is that most relationships fail, and I'm pretty sure it's not because you didn't book that trip to Cabo," McCartney writes as a rebuke to the idea that we always have to be trying harder in relationships. "If you must, read the summary of the hottest new books online," she advises instead of stressing about keeping up with the latest literary find. "Obviously your life is still the same and books don't change anything," she writes in her conclusion. The moral of the book, it seems, is not so much to give you a workable plan as it is to draw your attention to all the ways you're sabotaging yourself with unachievable goals.

Well, I'll tell you, I definitely did not sign up for this journey to learn something about myself. But, one night, I fretted about a pile of books I'm halfway through and debated making an appearance at two different events, and then, almost without thinking, decided to just not do any of it. I plopped down on the couch, turned on my Netflix, scrolled past all of the hit shows I've been meaning to watch, and turned on the first season of a show that came out four years ago. A little voice in my head chastised me for not spending my time picking something that everyone was talking about, or being social, or cutting fresh cilantro, or working. But another, louder voice reminded me "You could just not." So, at least, for a moment, I did.

I'd say that my experiment in doing just enough was, in general, a failure. Not because of anything wrong with the book, but because, as McCartney notes, the compulsion to do more, better, faster is a cultural issue. It's hard to escape, even for a week. But, in some small way, I imagine that trying to follow the tenets of this book, coming up short, and figuring "Eh, that's good enough," is the perfect first step.