In 1937, a young army wife sat at her typewriter in a rented house in Alexandria, Egypt. She wasn’t happy. Despite coming from an ebullient theatrical family, she was reclusive and agonisingly shy. The social demands that came with being married to the commanding officer of the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards were far beyond her. It was too hot and she missed England bitterly, though not the small daughter and new baby she’d left behind.

At the age of 30, she had already published four novels and two biographies. Yet 15,000 words of her new book were torn up in the wastepaper basket, a “literary miscarriage”. She knew the title but not what would constitute the “crash! bang!” of its plot, just that there would be two wives, one dead, and the name: Rebecca.

Inchingly, Daphne du Maurier’s difficult novel came together. She wrote it in the first person, from the perspective of a young unnamed narrator, who meets the dashing, yet unhappy Max de Winter while working as a lady’s companion in a grand hotel in Monte Carlo. The girl is anxious, observant, dreamy, terribly romantic, a perennial fantasist whose fears and insecurities bloom out of control when she becomes mistress of the haunting Manderley.

Rebecca is a very strange book. It’s a melodrama, and by no means short on bangs and crashes. There are two sunken ships, a murder, a fire, a costume party and multiple complex betrayals, and yet it’s startling to realise how much of its drama never actually happens. The second Mrs de Winter might not excel at much, but she is among the great dreamers of English literature. Whole pages go by devoted to her imaginings and speculations. The effect is curiously unstable, not so much a story as a network of possibilities, in which the reader is rapidly entangled.

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” Simone de Beauvoir said, and there aren’t many darker illustrations of what this might mean and what it might cost than Rebecca. The narrator is raw as an egg, practically a schoolgirl, with her “lanky” hair and bitten nails, her inability to talk to servants or run a house. Rebecca, on the other hand, is finished: lacquered and exquisite as the priceless china cupid her clumsy replacement breaks. It was Rebecca who created Manderley, turning the lovely old house into the apotheosis of feminine talents and virtues.

Of course, this paragon of beauty and kindness turns out to be a malevolent fake. In the Du Maurier family slang a sexually attractive person was a “menace”, and Rebecca unites both the word’s meanings. She is an animal, a devil, a snake, “vicious, damnable, rotten through and through”. She’s destroyed because of her poisonous sexuality, what the Daily Mail might euphemistically call her “lifestyle”.

Amazingly, the reader is somehow manipulated or cajoled into believing her murder and its concealment are somehow necessary, even romantic; that being cuckolded is a far worse fate than a woman’s death. It’s a grim reworking of “Bluebeard”, in which the murderer is suddenly the victim, adorable despite his bloody hands.

But who is really punished, and for what? Rebecca has a disturbingly circular structure, a closed loop like James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. It ends with Manderley in flames, but the first two chapters are also the conclusion. Husband and wife have been condemned to the hell of expatriation, in a hot, shadowless, unnamed country, staying like criminals in an anonymous hotel. It is apparent that they are revenants in a kind of afterlife, their only pleasure articles from old English magazines about fly fishing and cricket. The narrator attests to their hard-won happiness and freedom, while knowing it resides in a place accessible only by the uncertain routes of dream and memory, expelled from the Eden they never quite possessed.

¶

Du Maurier was under no illusions as to the bleakness of what she had written. “It’s a bit on the gloomy side,” she told her publisher, Victor Gollancz, adding nervously “the ending is a bit brief and a bit grim”. But her predictions of poor sales were inaccurate. Rebecca was a bestseller; 80 years on it still shifts around 4,000 copies a month.

What really startled her was that everyone seemed to think she’d written a romantic novel. She believed Rebecca was about jealousy, and that all the relationships in it – including the marriage between De Winter and his shy second wife – were dark and unsettling. (“I’m asking you to marry me, you little fool” hardly betokened love between equals.) The idea had emerged out of her own jealousy about the woman to whom her husband, Tommy “Boy” Browning, had briefly been engaged. She had looked at their love letters, and the big elegant “R” with which Jan Ricardo signed her name had made her painfully aware of her own shortcomings as a woman and a wife.

It wasn’t just that Du Maurier was shy, or disliked telling servants what to do. Though she was beautiful, she had never wanted to participate in the masquerade of femininity. She didn’t want to be a mother (at least not of daughters) or wear dresses, though she painted her face even to go on her beloved rain-lashed walks. What she liked was to be “jam-along”, scruffy, perpetually in trousers, messing about in boats or living at large in her own head.

As Margaret Forster’s revelatory 1993 biography made clear, Du Maurier had been like that since childhood, always dreaming up other possibilities, never certain that people, or even time, were as stable as they seemed. She certainly wasn’t. From a very young age she was what she called a “half-breed”, female on the outside “with a boy’s mind and a boy’s heart”.

As a child, this didn’t pose problems, especially in a family of actors. She dressed in shorts and ties and spent most of her time pretending to be her alter ego, Eric Avon, the splendid, shining captain of cricket at Rugby. But as she reached adulthood, this boy self “was locked in a box”. Sometimes, when she was alone, she opened it up “and let the phantom, who was neither boy or girl but disembodied spirit, dance in the evening when there was no one to see”.

This hidden boy exploded into the light in 1947, when Du Maurier met and fell in love with Ellen Doubleday, the wife of her US publisher, and the addressee of the letter in which these revelations were made. Her feelings were not reciprocated, but they opened the gates for a later affair with Gertrude Lawrence, an actor with whom her father had also been involved.

Du Maurier’s sexuality is complicated to understand. The word transgender was not yet in common currency. She didn’t think her desire for women made her a lesbian and fought against her “Venetian tendencies”. (Heterosexual sex was known in the family, even more exotically, as “going to Cairo”.) Actually she felt she was a boy, very much in love, and stuck in the wrong body. At the same time – perhaps pragmatically, perhaps not – she was a woman committed to staying married to her husband.

She was by no means the only writer to feel herself two things at once. Many critics have caught a similar note in Ernest Hemingway, who often wrote about sex as a place in which genders could be temporarily and blissfully exchanged. Virginia Woolf, too, experienced herself as protean, slipping between sexes; her gender-shifting, time-distorting romp Orlando gave voice to her feelings for her lover Vita Sackville-West.

How much of Du Maurier’s sexuality is visible in Rebecca? The narrator repeatedly casts herself as an androgyne. She offers herself to Maxim as “your friend and your companion, a sort of boy”. The full heat of her desire is for Rebecca. She speculates about what her body might have looked like: her height and slenderness, the way she wore her coat slung lazily over her shoulders, the colour of her lipstick, her elusive scent, like the crushed petals of azaleas.

She isn’t the only one obsessed with Rebecca’s absent body. Mrs Danvers serves as a much more obvious proxy for Venetian tendencies. In the novel’s most sexual scene, “Danny” forces the narrator to put her hand in Rebecca’s slipper and fondle her nightdress, while she murmurs an incantation to Rebecca’s hair, her underwear, how her clothes were torn from her body when she drowned.

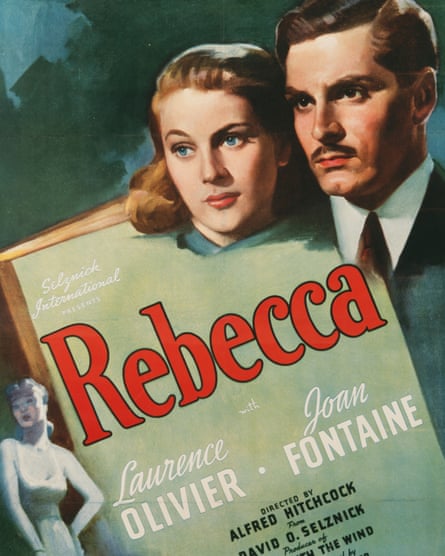

No wonder Mrs Danvers’ was the face that launched a thousand drag acts. She was embodying closeted lesbian realness even before Judith Anderson catapulted her into the high camp stratosphere in the Hitchcock film. Mind you, Anderson is given a run for her money by the revelation that Philip Larkin used to cheer himself up by looking in the mirror and declaiming throatily: “I am Mrs de Winter now.”

¶

It’s not unusual for a novel to contain traceable elements from its author’s life. What’s odd about Rebecca is that it seemed somehow predictive, too packed with things that belonged not just to Du Maurier’s past but to her future, as well.

![‘[Du Maurier] loved the house feverishly, calling it “my Mena”, even though it was freezing, rat-run and chunks of the old wing kept crashing off’ ... Menabilly.](https://i.guim.co.uk/img/media/832271d22aa5db8c618340ee41ec4e7f0b60e945/0_0_1024_679/master/1024.jpg?width=445&dpr=1&s=none)

The most noticeable is Manderley, “secretive and silent as it had always been … a jewel in the hollow of a hand”. Manderley was based on Menabilly, an abandoned house near Fowey in Cornwall, which had bewitched Du Maurier as a girl. Like Manderley, Menabilly was strangely elusive. After she returned from Egypt, she managed to lease it from the owner and remained based there for most of her life. She loved the house feverishly, calling it “my Mena”, even though it was freezing, rat-run and chunks of the old wing kept crashing off. But she never quite possessed it, and in 1967 she was expelled after years of legal battles. Though she could still walk its grounds, Mena was as lost to her as if it had been swallowed in a fire.

“What is past is also future,” she once observed. When, in 1957, her husband had a breakdown and was discovered to have been having two affairs concurrently, Du Maurier wrote a long letter to a friend, in which she speculated about how her own life had become entangled with the plot of her most famous book. Was her husband identifying her with Rebecca, she wondered, and her writing hut with the sinister cottage on the beach? Would he shoot her in a blind access of rage, and take her body out in Yggie, their beloved boat?

She was under a great deal of stress at the time, but the fantasy aligned with her feelings about the oddities of time, how it seemed to run simultaneously, so that the distant past sometimes came very close, or repeated in inexplicable ways. She explored this in novel after time-slip novel, from her 1931 debut The Loving Spirit to The House on the Strand (1969), in which a young man takes an experimental drug that allows him to view events taking place in his own house in the 14th century.

The haunted house on the Strand is rather like a Du Maurier book in its own right. Her novels are storehouses in which she deposited emotions, memories and fantasies. Their function was intensely personal, but also public. If you’ve read Rebecca you have no doubt wandered Manderley in your mind, passing through the tunnel of scarlet rhododendrons in the hope of tea and dripping crumpets by the library fire, entering vicariously into moods of love and terror.

Du Maurier was not the most intellectual of writers. What she did was build emotional landscapes that can be entered at will, in which difficult and untamable desires were given free rein. Maybe because of her relationship with gender, she was able to make worlds in which people and even houses are mysterious and mutable, not as they seem; haunted rooms in which disembodied spirits sometimes dance at absolute liberty

- The Lonely City by Olivia Laing is published by Canongate. Rebecca (80th anniversary edition) by Daphne du Maurier is published by Virago on 1 March.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion