Early in my career, I had an unforgettable meeting with a prospective retiree.

Sitting second chair to a senior advisor and mentor, I was meeting with an affluent prospect who had accumulated a significant retirement portfolio, and who wanted to learn more about our services.

After exchanging a few pleasantries, the rather matter-of-fact gentleman asked us point blank, “How will you generate income for me from my retirement portfolio?”

It was a perfect setup for us to talk about our investment management process — in essence, that we didn’t just focus on dividends and interest to generate income, but rather created a more total return approach. This in turn dovetailed with our philosophy of managing portfolios for long-term return to keep up with inflation.

After about 20 minutes of proudly walking through our investment process for retirees, the prospect simply looked at us, somewhat exasperated, and asked again, “But how will you get the income from my retirement portfolio into my checking account so I can pay my bills?”

To this, we answered, “For all of our clients, we set up a monthly ACH transfer directly from your brokerage account to your checking account so you can pay your bills every month. And our process ensures that there’s always cash available to transfer.”

“Great,” he said. “That’s what I needed to know. Not all that other investment stuff. If I wanted to deal with that, I’d be doing it myself. Now, how do we get started?”

I relate this anecdote because creating income streams in retirement that replicate or at least approximate the predictable income of a working life is often top of mind for clients, whatever their financial circumstance. Indeed, the retirement “paycheck” is such a pervasive client expectation that advisors really need to think about how our holistic strategies align with that very real client need.

THE ONGOING PAYCHECK

For most of our working lives, paychecks are deposited on a regular basis — most commonly, according to the

And then one day, the paychecks stop. This creates one of the most pressing yet natural questions for retirees: How will I replace those ongoing paychecks so I can fund my expenses for the next 30-40 years?

In the early days of the modern retirement planning, i.e., the post-World War II era, the solution to this situation was rather straightforward.

However, the inflation of the ‘70s

And fortunately, a well-diversified portfolio of dividend-paying stocks also typically bundled a well-diversified series of dividend distribution dates — perhaps not quite distributing retirement paychecks as consistently and evenly as bond coupons did, but more than enough to be manageable.

The added complication of introducing dividend-paying stocks to the retirement portfolio, however, was that stocks also could produce potentially quite substantial capital gains. In fact, through the ‘80s, when retirement investors shifted from interest-paying bonds to dividend-paying stocks to keep up with inflation, not only did dividend payouts more than keep pace with inflation — rising 80% through the decade, while inflation was only up a cumulative 57% — the raw price level of the S&P 500 also appreciated by 150%. This meant retirees suddenly had another very powerful tool at their disposal for generating retirement paychecks.

That said, capital gains are not nearly as stable or consistent as dividends or interest, producing outsize potential distributions in some years but little to none — or even outright losses that force principal liquidations — in other years. Consequently, while capital gains are capable of generating substantial amounts of additional retirement income, they are far less conducive to a steady approach of generating retirement paychecks for regular deposit into a retiree’s checking account.

The significance of this evolution in the sources of retirement income from interest to dividends to including capital gains as well — and the potential need to rely on principal in years where capital gains don’t occur — is that when the sources of retirement income are so unstable, it effectively begins to dissociate the generation of income from simply creating retirement cash flows instead that may or may not be income in a traditional sense.

And the situation is further complicated by the fact that tapped principal may or may not be taxable income, depending on whether it’s from an IRA or not, which just further dissociates income for tax purposes from retirement cash flows to cover retirement spending needs.

The good news is that there’s actually more retirement income and wealth potential to be created by navigating the investment intersections of interest, dividends, capital gains and principal; and the tax dynamics of ordinary income, qualified dividends and long-term capital gains, principal liquidations, pre-tax retirement account distributions and the use of Roth-style tax-free distributions (or IRA conversions to them). The bad news is that it becomes remarkably difficult to simply figure out where the actual cash will come from to generate those retirement paychecks.

RETIREMENT PAYCHECK STRATEGIES

Of course, the simplest and most straightforward solution to generating steady retirement paychecks is simply to eschew portfolio-based investing altogether and purchase a traditional

This brings us back to the question of how retirees and their advisors should generate retirement paychecks from a diversified, total return retirement portfolio.

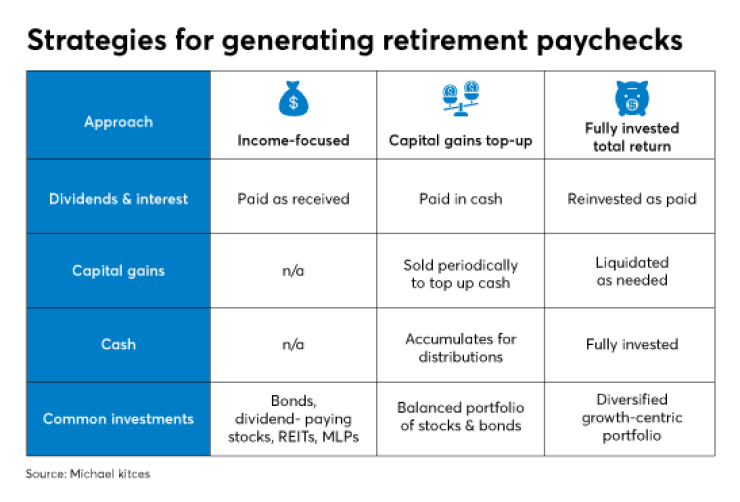

The first option is the more traditional income-based approach — that is, to simply invest in vehicles that can produce a steady stream of cash flows in retirement, and then pay out those income distributions as they are received. This might be buying into a mixture of bonds that pay interest and stocks that pay dividends, along with more recent additions to the income-portfolio mix like real estate — e.g., via REITs — and Master Limited Partnership as well.

With this approach, capital gains are largely ignored, and/or are not even actively invested toward in the first place. Instead, the portfolio is simply invested in income-producing assets, whose ongoing income payments will be transferred to or directly paid into the retiree’s retirement account.

The risk of the income-based approach is that investment markets don’t always pay the level of income that one desires, as has been the case in the low-yield environment of the past decade in particular. This in turn can drive some investors to stretch for yield by taking on additional investment risk, and increasing the possibility that the income itself may stop, or at least be cut, in difficult times — e.g., a recession that causes high-risk bonds to default.

One tactical approach to this problem is to use capital gains to supplement, or top up, income to generate retirement distributions. For instance, interest and dividends might still be accumulated first, and held in cash until paid out. But on a quarterly or annual basis the available cash position may be supplemented by rebalancing the portfolio — effectively liquidating whatever investment was recently up the most — to generate additional cash for the coming three or 12 months on top of whatever the interest and dividends were ultimately providing.

In the event markets were down and there was nothing up to rebalance, the next quarterly or annual distribution supplement might be designated to come from cash instead — i.e., from principal, to avoid liquidating equities while they’re down.

This top-up approach was appealing in the past partly because it helped minimize transaction costs and trading activity by first accumulating any/all available interest or dividends, and then liquidating just enough to top up the required distributions on an ongoing basis. Advisors or retirees particularly sensitive to trading costs might generate cash from capital gains on an annual basis, while those with more modest transaction costs might do so quarterly instead, to keep more of the portfolio fully invested.

However, as transaction costs have continued to decline further, some advisors now opt for a pure total return approach that invests in a more growth-oriented portfolio, and to the extent there are any interest and dividends, they are fully and immediately reinvested to avoid any ongoing cash drag in the portfolio.

In turn, when the retiree needs distributions, it’s time to simply sell the desired investments if/when/as needed to generate that cash, at the exact moment it is needed to fund a retirement paycheck. After all, in a near $0 transaction cost environment — because unlimited trading is permitted via a single wrap fee, and bid/ask spreads are $0.01 — arguably there’s no reason to ever hold any cash at all, or even income-producing investments that generate cash. Even if a recently received interest or dividend check will be needed in just a few weeks, it could still be invested in the meantime and liquidated later.

For tax-sensitive clients, lot-level accounting ensures that the shares sold will be the ones just purchased that will still be mostly basis and have little short-term capital gains exposure.

These are the best and worst places to consider based on total tax burdens.

WITHDRAWAL POLICY STATEMENTS

Even from something as simple as a total return portfolio that combines interest, dividends and capital gains, there is a non-trivial amount of complexity in turning all the various moving parts into a steady series of ongoing retirement paychecks for retirees. The key is recognizing that while a retirement portfolio may have multiple sources of return, most retirees simply want to pay their bills the way they’ve already been paying them, which is with cash that simply shows up in their bank account on a regular basis. And after retirement, when actual employee paychecks disappear, this must be accomplished from the available retirement portfolio and other assets.

Accordingly, some of the key practical components that must be considered for any portfolio-based retirement income process include:

- Dividends and interest: Will they be swept to cash, distributed immediately or reinvested for future liquidation?

- Cash: Will it be allowed to accumulate? What will be done to increase/supplement it over time? Is there a better place for it to sit that generates a more favorable yield?

- Liquidations: What will be liquidated if additional cash flows are needed, either on an ongoing basis or for one-time large expenditures? Will a rules-based system or other policy be established to determine formulaically what to liquidate as needed — e.g., from stocks if the market is up but from cash if the market is down — or rebalanced from whatever investment is most overweighted, or rebalanced from whatever investment has had the biggest recent run-up?

- Cash reserve: Beyond having the cash to distribute to the retiree, will an additional cash bucket be held to smooth out distributions from potentially volatile sources?

- Distributions: Advisors historically have rebalanced on an annual or perhaps quarterly basis, but most retirees are accustomed to monthly or even bi-weekly paychecks. How often will distributions be made?

- Accounts: From which accounts will distributions occur, given that many retirees have a mixture of up to three different primary account types — taxable accounts, tax-deferred retirement accounts and tax-free Roth-style accounts? How will distributions for paycheck purposes be coordinated with ongoing tax planning for the retiree — e.g.,

tax-efficient drawdowns orsystematic partial Roth conversions ?

- Coordination: How will retirement distributions be coordinated with the other available sources to generate retirement cash flows, from

Social Security benefits — which may or may not be delayed — to potential uses of annuities, and even reverse mortgages to supplement retirement cash flows? Will retirement withdrawals have to be adjusted dynamically to handle these other cash sources?

In the end, the point is not necessarily to pick any particular methodology for generating retirement withdrawals, but simply to recognize that some clear and consistent policy is needed — ideally, one that can be applied consistently to a wide range of clients and situations.

This in turn can then be

In fact, the whole point of a withdrawal policy statement — as distinct and separate from an investment policy statement — is to recognize that generating retirement distributions, i.e., re-creating paychecks in retirement, is not just a function of how the portfolio will be invested alone. Rather, it encapsulates a whole separate but related set of policy issues, from how interest and dividends will be handled; whether/how capital gains will be generated and used; the proactive use of cash; the frequency of distributions; and how the strategies will be coordinated with both the impact of taxation and the availability of other assets and income sources.

The bottom line is simply to recognize that for many retirees, generating income in retirement isn’t merely or even primarily an investment problem. In some cases, it’s a far more straightforward mechanical problem — that is, how the cash will be generated to appear in the bank account, as the retiree has been accustomed for the past several decades.

Though in practice, generating those retirement paychecks from a diversified portfolio is not necessarily as simple as it may seem — at least not until decisions are made about the specific retirement income process and policies that the advisor intends to use.

So what do you think? How do you mechanically generate retirement distributions from a portfolio to create retirement paychecks? How does your liquidation methodology impact the rest of your investment and tax-planning approach in retirement? Please share your thoughts in the comments below.