Mack-Cali’s Michael DeMarco Talks Jersey City and the REIT’s Boardroom Musical Chairs

By Rey Mashayekhi May 9, 2018 9:00 am

reprints

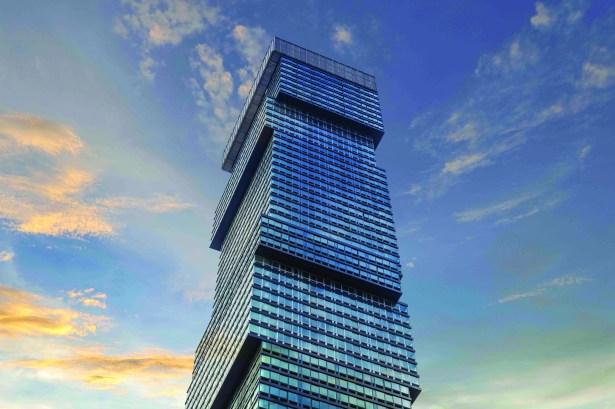

For a New Yorker who seldom makes the trip across the Hudson River, a walk along the Jersey City, N.J., waterfront can be a revelation. Glassy office and residential buildings, many of them new developments, tower over the downtown area, providing workers and residents alike with stunning views of the Manhattan skyline just to the east.

Located in a 12-story building known as Harborside 3—part of the larger Harborside office complex that it owns on the waterfront—the offices of Mack-Cali Realty Corporation, one of New Jersey’s largest commercial real estate landlords, take full advantage of those views. The company relocated its headquarters to Jersey City from Edison, N.J., in 2016—a move emblematic of a wider shift across the real estate investment trust’s portfolio.

Traditionally among the most prolific owners of suburban office parks in the region, Mack-Cali has offloaded hundreds of millions of dollars of suburban office assets in recent years—opting instead to focus on more millennial-friendly office and multifamily properties in higher-density, urban areas. The REIT—which now owns and operates 15.4 million square feet of office space across the Northeast, as well as more than 5,800 residential units—sold off $528 million worth of properties in 2017 alone, with plans for another $375 million to $425 million in dispositions in 2018. In turn, it has looked to redirect its resources into expanding and upgrading its waterfront-centric commercial and residential holdings.

Spearheading that transition has been Michael DeMarco, Mack-Cali’s CEO. The 58-year-old Jersey City native, who now lives in Spring Lake, N.J., with his wife, joined the company as president and COO in 2015 alongside then-CEO Mitchell Rudin. The pair of them were appointed to shepherd Mack-Cali into a new era following the departure of longtime president and CEO Mitchell Hersh, but things didn’t work out exactly as planned; less than two years later, DeMarco was promoted to CEO, while former Brookfield executive Rudin found himself bumped down to vice chairman of the firm.

A quick-talking, high-functioning, self-assured and insightful conversationalist, DeMarco—flanked in his office by his four diminutive teacup Maltese dogs—recently sat down with Commercial Observer to discuss that switch, as well as a varied career that has included a lengthy tenure at investment bank (and Great Recession casualty) Lehman Brothers and stints at real estate investment giants Fortress Investment Group and Vornado Realty Trust (VNO).

Along the way, DeMarco touched on his efforts to transform Mack-Cali’s portfolio and why the company has high hopes for its Jersey City stronghold.

Commercial Observer: Let’s start with your background. It’s interesting as you were born and raised in Jersey City, and now you’re head of a company that’s seeking to transform your hometown into a viable residential and commercial destination.

Michael DeMarco: I’m the son of a bar owner from Jersey City. My father gave me $1,500 to go to college [at Pace University], and the rest I earned working my way through college. I learned a craft—I became an accountant—but I wanted to have a mind that could learn other things, so I had a minor in history. I became a CPA [at Arthur Andersen], I did audit and tax work, and then I went to the University of Chicago and got my MBA in finance and economics with a minor in statistics.

I was a vice president and senior managing director at Lehman from 1993 to 2007, and in 2007 I joined Fortress as a partner and managing director and ran real estate for North America. Then [in 2010] I went to work for [Michael] Fascitelli and [Steven] Roth [at Vornado] for three years as executive vice president of special projects, did dispositions and acquisitions.

So between Wes Edens and Pete Briger [of Fortress] and Mike Fascitelli and Steve Roth, I got my six years of on-the-ground experience, being thrown into the deep end and told to swim laps with cinder blocks. You get good at it—you can either sink or swim.

Were you at Lehman when everything exploded with the global financial crisis?

I wasn’t there at the end; I left before. I was there at the height—I joined as it was getting spun off from American Express [in 1994] and helped build the real estate business. I was one of the pioneers of the CMBS business, started doing it in 1991. A lot of the [methods] that people use today, like pooling and master servicer contracts, were all being done by Lehman in the early days. We held the title as the most innovative shop with the largest volumes for six or seven years, at least until around 2002; then the business became more diffused and people started doing balance sheet lending, and then the whole world blew up.

I migrated from lending and did true investment banking; covered SL Green, Vornado, Macerich, Simon [Property Group], General Growth [Properties]. I think I was in the top 15 bankers globally three or four times in my last five years at Lehman, which is hard to do if you’re not a group head. I was particularly good; I was 10 percent of their equity book one year. I did a lot of [mergers and acquisitions], a great deal of advice work. When Equity Office was being sold, I represented [Vornado] on the buy side; I cost [Blackstone’s] Jon Gray about $2 billion, personally [by driving up the price of the portfolio].

Is it safe to say nobody at Lehman knew what was on the horizon in 2008?

I think if you looked at it at the time, you should have noticed certain signs, but you didn’t think it would be that. What was really not understood by the public, and I think is still misunderstood, is why such a small segment of the financial world, the housing business, had that devastating an effect on the entire financial system.

It was basically too much money and too much leverage in the system: Goldman was overleveraged, Morgan Stanley was overleveraged, the hedge funds were all overleveraged. In the single-family business, if your uncle had been overleveraged on his house, there might have been 30 bets on [the mortgage by financial institutions]. So when your uncle defaulted on $100,000, it cost them $3 million. And you’re looking at it and saying, How can that be? How can single-family homes take down Bear Stearns and Lehman and Merrill Lynch? It’s amazing. But when you were out chatting with people and you found the hairdresser or secretary who was buying two or three condos on financing, you should have known.

What was your time at Vornado like?

I was hired by Fascitelli when he was CEO to run special projects. It was an interesting shop; you had [GGP CEO] Sandeep Mathrani there, [Seritage Growth Properties President and CEO] Ben Schall, [Paramount Group CFO] Wilbur [Paes]. You had like six of us who all came out of the same shop who now either hold CFO or CEO [positions] at some of the top companies in the space. It was a good place to work.

Though Fascitelli was running things as CEO at the time, you always get the sense that Vornado is Steven Roth’s company first and foremost, don’t you?

Totally—Mike and him were partners, but it’s always been Steven’s shop.

We recently ran a feature about how Roth is looking to reposition Vornado’s assets around Penn Plaza to compete with new Far West Side developments like Hudson Yards.

He’s been talking about that since 1986. He acquired that position in ’86, and he’s never added to it. He’s very happy; he milks it. He’s going to do something one day, but it’ll be on his time.

So given all that real estate-related experience you were able to gather, would you say you were prepared for your role here at Mack-Cali?

I was probably not well suited for one aspect: it was a large company. You had 600 employees.

There are about a dozen men and women who I’ve mentored in my career, because I believe in that. There’s an old joke that [Andrew] Farkas once told me; he used to have a company in South Carolina, and they say there that if you drive down a road, and you see a tortoise on top of a fence post, you kind of know they got there with help. So if you look at careers, you are always the beneficiary of someone’s assistance; you may not realize or appreciate it, but you are. So David Lazarus at Eastdil? My protégé. Scott Weiner at Apollo, Andy Richard at [Credit Suisse], David O’Reilly at Howard Hughes—there’s a dozen guys I can point to who I’ve actually trained, that think of me as [a mentor].

That makes me good at these types of conversations, which I would have often. But running a company with 600 people, you’ve got to have a clear voice and communicate accordingly. It took me a little while; I’d say I’ve done it well, but it was still different.

Let’s talk about the situation with Mitch Rudin. How did it come about that you effectively switched roles—with you replacing him as chief executive of Mack-Cali—two years after you both joined the company?

When Mitch Hersh left, the company had also experienced a loss the year before of its CFO and general counsel. That troika had been together for 15 years, so the board decided they wanted to bring in more than one person to replace Mitch, because they were really looking to replace the [other] positions [as well].

I was brought in because I had the finance side and operational side. I didn’t even know if I wanted to interview—it’s New Jersey, and I was looking to do something else; it’s suburban office, which is not my best category; and Mack-Cali had a reputation that was, to use the German side of my family history tree, verboden [forbidden]. But the headhunter induced me to go.

I only have one speed; it’s just the way I am. If I do something, I do it very well. I believe in that; I believe in excellence in all things, if they matter to me. So I went to the interview and I prepared a 30- to 40-page PowerPoint presentation as if I was an equity analyst. [Mack-Cali Chairman] Bill Mack says, “You have a presentation? Wow, nobody brings a presentation to an interview.” But it allows you to formulate your thoughts and dictate the pace. You ever play tennis? You always want to hit, not receive; you want to put the spin on the ball and put it where you want, and make the other guy react to that. So I controlled the interview; I read 10 years of financials and I went and visited the assets. I prepared like I had prepared for every interview in my career, which had made me successful up to that point.

So I went through the presentation and they were impressed, and they came back and said, “Listen, we want to hook you up with somebody,” and they found Mitch Rudin. The problem with Mitch was—I tend not to worry about titles. I’m not a big person on rewarding myself, I think it actually weighs you down and also leads to bad behavior. Mitch was a broker; guess what brokers really love? Titles. Vice chairman, executive vice chairman, vice chairman of metropolitan region—they got more vices than an addict. I basically said, “Mitch, if you want to be CEO”—we were supposed to be co-CEO, but I thought it was confusing—“I’ll be president. But we’ll be equal; we get paid the same, our contracts will be exactly the same, every word.”

I embrace risk. I’m not a risk-averse individual, nor am I a risk plunger—I’m a risk measurer. My job was to embrace risk, because without risk, you won’t have return, and without return you weren’t going to change this place. Mitch wasn’t really big about embracing risk, he was much more risk-averse. He came in and he liked being CEO; he liked the title of it. I’m a pretty common guy—I think I still have the same box of business cards. I don’t think I ever opened it; it doesn’t do it for me.

We’re still friends; he’s down the hall. It’s no big deal. I spent my life advising people who were wealthy and doing finance and real estate, and Mitch was a leasing guy. He just didn’t have the right skill set for the public market, and I think he realized it. We had an agreeable meeting and then we just flipped roles.

Mack-Cali has shed millions of square feet of suburban office assets and doubled down on more concentrated markets like Jersey City and Hoboken. Many developers are pursuing a similar business plan, but can you discuss how you’ve formulated your approach?

To turn this company around, you had to embrace change—if you don’t embrace change, change will embrace you. It’s New Jersey; it’s a rapidly changing market. You’re under 30; in your world, this [holds up cell phone] has been around forever, literally forever. You probably don’t remember flip phones, and you definitely don’t remember the phone in your mother’s kitchen with the cord. You also think interest rates are always at 2, 3 percent, and that it’s very easy to date—you just go on the web, find someone and swipe. These are things that didn’t exist in our childhood. But if I want to run a real estate company, which I really do, I have to understand you because my customer is worried about attracting, retaining and recruiting you. I have to have the right buildings.

If you go downstairs, where you walked in, that was a lobby [Harborside Atrium] that didn’t have one piece of furniture when I took over—not one chair. My predecessor didn’t like people in the lobby, he thought it was incorrect; I embrace it. You go to my lobby, it’s an open network, it’s amped to the max—you can hold a tech conference down there. We host wine fests, beer fests, whiskey fests, we did a Super Bowl party, we did a New Year’s Eve party down there—I’ve got something there all the time. If you look out the window, that piece of land down there, that’s a beer garden in the summertime.

The portfolio I was given had things that were really good but were noncore, like a condominium interest on 125 Broad Street [in Manhattan] and two buildings in D.C. which were nice buildings and marketable, but there was nothing else matching it [in the portfolio]. You had things that were really damaged; there was an office park in Maryland that never should have been bought that had really drifted, and a number of assets in New York and New Jersey that were also the same way.

I looked at the situation and said, I’m in the money business. I looked at what was best, and what was worse, and I took a very iterative process, which I always do. I looked at the portfolio and said, What do we really need to sell? So we sold the things that were the easiest to get rid of and some of the worst to get rid of, and worked from the bottom up. If you want change, embrace all of your problems—don’t just embrace some. So there was nothing in our portfolio that we walked away from and said, Oh, that’s a deal that’s difficult, we’ll deal with it later. We dealt with every problem. And then we invested in multifamily, brought on some partners, created cash flow.

I took a meeting at Nareit [National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts conference] the week we got hired; I got hired on a Wednesday, and that Monday we did a Citibank dinner at Nareit for 50 investors where we rented a table. Some of us hadn’t even met each other. We went into the meeting and did it extemporaneously—which I’m quite capable of—and said, “We’re basically going to change. I don’t know where exactly it’s going, but I know which direction it’s going in: more modern, more new; more for [younger people], less for the guy who’s 60 years old.”

And that’s it; it’s pretty simple. We build residential for the younger generation, and I try to own office for an employer that wants to attract the millennial class, too. Jersey City sells at a discount to Manhattan, and it’s closer [to Manhattan] than Brooklyn; you commuted today here with ease, I imagine. People haven’t done it enough, but now more and more people are moving over because we’re getting more and more apartments. This is Brooklyn five or seven years ago, and we’re just beginning.

Mack-Cali had around 25 million square feet of office space across its portfolio when you arrived, with much of that suburban office. What are you at now?

Fifteen [million square feet], going down to probably 11 [million square feet] by the end of the first six months of this year. I thought I could transform office sites into apartments, I thought it would be easy—but it’s a two-year process. We sold buildings out west [in suburban New Jersey], and we own a building in Hoboken [111 River Street, which Mack-Cali acquired for $235 million in 2016]. We’ve added to our portfolio of sites in Jersey City; we have the best portfolio of land in New Jersey, which people are envious of. And we have a real portfolio of multifamily assets.

The company recently completed the Jersey City Urby—a 69-story, 762-unit rental tower that is now the tallest residential building in New Jersey. What’s your investment thesis for Jersey City as a multifamily market worth investing in?

It’s a great commuter market to get into work [in Manhattan]. Every luxury building in this market here has a pool—that’s stupid, right? They all have outdoor pools, indoor gyms, rock climbing, indoor garages attached to the building; you can park a car here for $220 [per month]. It’s $550, $600 in Manhattan. And if you live in New Jersey, you don’t pay New York City resident tax and you save a couple bucks.

Mack-Cali also has a fair share of exposure in suburban multifamily markets. Do you still see that sector doing well?

Not everybody wants to work in Manhattan. There are a lot of employers—[many] of the top drug companies in the U.S. are headquartered in New Jersey, and most of them are in Morris County, so we have big holdings there. If you’re a scientist, for example, and you make a couple hundred grand a year, you want to live in Chatham, you want to live Morristown, you want to live in Randolph, or you want to live in Essex County, in Short Hills or Millburn or Summit.

And what about across the river? Does Mack-Cali have any desire to get into the New York City market?

It’s very crowded to begin with and there’s no sign it’s cracking. I think New Jersey offers better appreciation for lower risk. I’d be more likely to go to Brooklyn than Manhattan. If somebody said to me that you could buy a portfolio like Forest City’s, for example—to combine the two of us would be an interesting play, right? Because you’d have MetroTech and Jersey City, and two different multifamily platforms.

You haven’t had those discussions, have you?

People have said I should actually take a shot at it, because I’m good at cleaning things up. My fundamental skill is that I’m a problem solver. If you come to me with a problem, I’ll give you what I think is the best advice I can, relatively expeditiously, because it’s the way I think. Everything with me is about going from point A to point B as efficiently as possible—everything I do. Why do I have the dogs come in? To be honest with you, because people like them around, and they tend to be stress reducers and they amuse me. And I spend a lot of hours here.