Treating Scleroderma When Neuromyelitis Optica Also Present ‘Challenging,’ Case Study Reports

People with scleroderma can develop autoimmune diseases like neuromyelitis optica (NMO), a condition that affects the nervous system — especially the nerves of the eye and spinal cord, a case report suggests.

Correctly diagnosing a co-occurring autoimmune disease help to ensure that scleroderma patients receive proper care early, which can avoid complications, the researchers emphasized.

The study, “Demyelinating syndrome in systemic sclerosis and neuromyelitis optica,” was published in the journal BMC Neurology.

NMO patients are known to have a higher incidences of other connective tissue and autoimmune disorders, including lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Sjogren’s syndrome, than the general population. However, cases of scleroderma and NMO in the same person are rare.

Researchers at the University of Miami and JFK Medical Center detailed the case of a 44-year-old Hispanic woman with both NMO and scleroderma.

The woman went to the hospital because she had hiccups that would not stop, vomiting, and difficulty with swallowing. Her vital signs on admission were stable. A physical examination showed thickening in the skin of the fingers, and lab exams showed low sodium and potassium levels, which were successfully treated with fluids and electrolytes.

The next day, she reported having blurry vision, weakness, and paralysis and loss of sensation in the lower limbs, which also showed as reduced muscle tone.

Doctors took a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the brain and spine, which showed small brain lesions, and injuries and inflammation in the upper region of the spine.

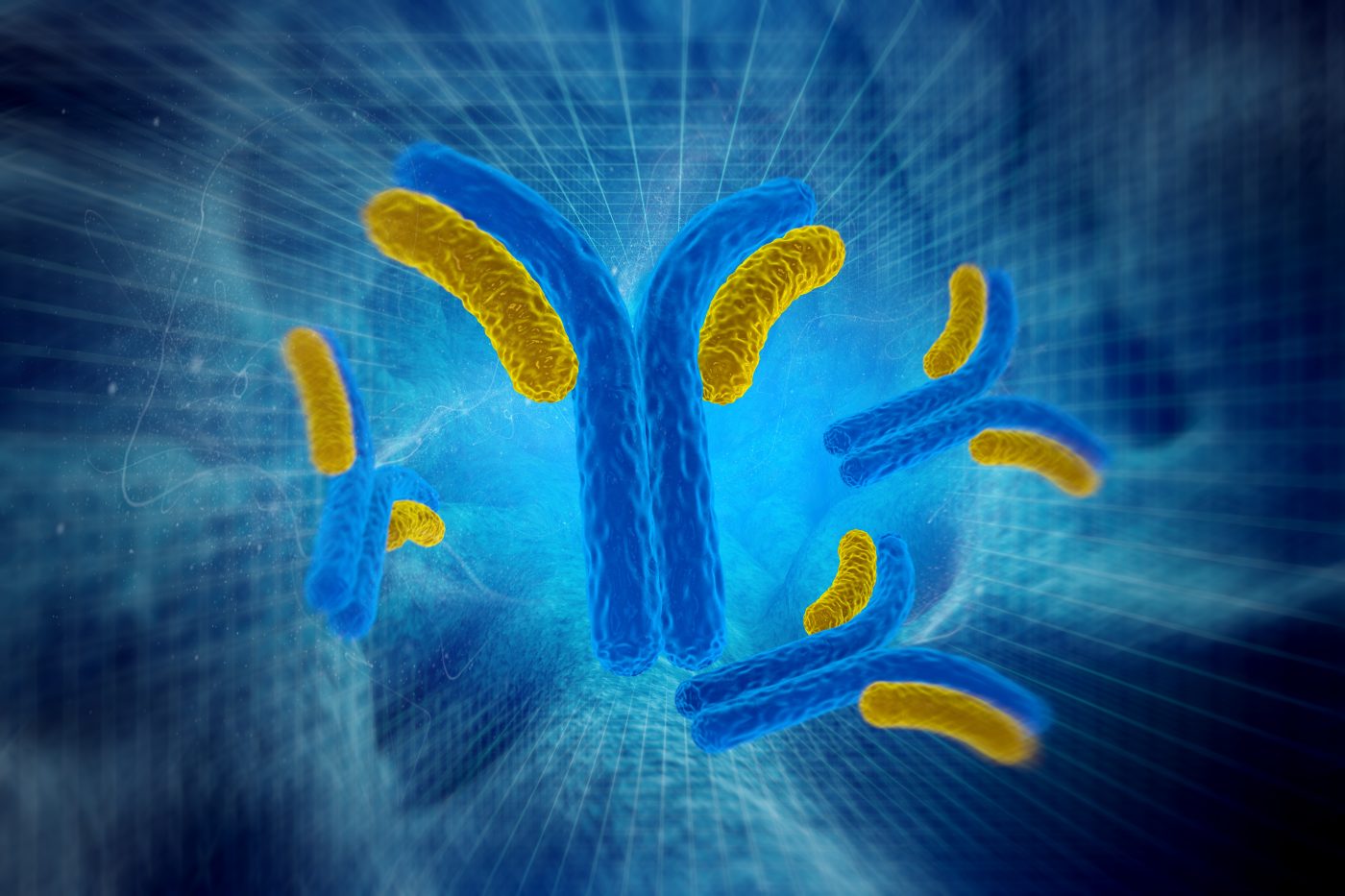

Lab exams were positive for autoantibodies — proteins that wrongly attack healthy cells — associated with NMO and scleroderma, which led to the diagnosis of both autoimmune diseases.

The woman started treatment with high doses of steroids, which improved her vision within two days but had little effect on her motor symptoms. After five days of treatment, she had a steroid-induced scleroderma renal crisis, a side effect of this medication, that caused high blood pressure and kidney failure.

Steroids were stopped, and the patient started treatment with an ACE inhibitor (a heart medication), which resulted in a normal blood pressure and a slow recovery of kidney function.

The woman then started treatment with immunosuppressants, first azathioprine, which was discontinued because it led to toxicity in the liver, and then rituximab, along with physical therapy. Her motor abilities gradually improved over a year of treatment. However, she experienced relapse episodes that included painful spasms, which were treated with muscle relaxers and antiseizure medication.

The coexistence of scleroderma and NMO “presented a challenge where the patient underwent aggressive physical therapy and necessitated an intervention with rituximab to achieve an appropriate clinical response,” the researchers wrote.

This case “highlights the need for proper diagnosis and treatment of coexisting autoimmune conditions, as well as the recognition of possible life-threatening side effects of conventional first-line steroid therapy,” they added. According to the team, patients with acute neurological manifestations should be tested for specific autoantibodies.

Cases of co-occurring NMO and scleroderma are rare, and since the underlying causes of both diseases remain unknown, it is difficult to say if their origin is related, the researchers also noted.