Post-Brexit Britain: Johnson gets an EU-FTA deal

Boris Johnson has won an outright majority in the Commons and will take forward the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement. This blog by Cambridge Econometrics founder, Terry Barker, looks at the potential economic consequences. This is the first of two blogs and looks at the prospects for a Free Trade Agreement with the EU (EU-FTA) and its consequences for the UK economy.

The second blog explores a scenario in which Johnson fails to agree an EU-FTA by December 2020 and chooses to exercise UK sovereignty through a chaotic no-deal Brexit – an option that he has repeatedly mentioned in his election campaign.

Disclaimer: the views in this blog are strictly personal and in no way do they represent those of the institutions with which the author is associated, namely Cambridge Econometrics Ltd., the University of East Anglia and the University of Cambridge.

Brexit has already damaged the economy

Brexit looks as though it has already inflicted serious damage on the economy.

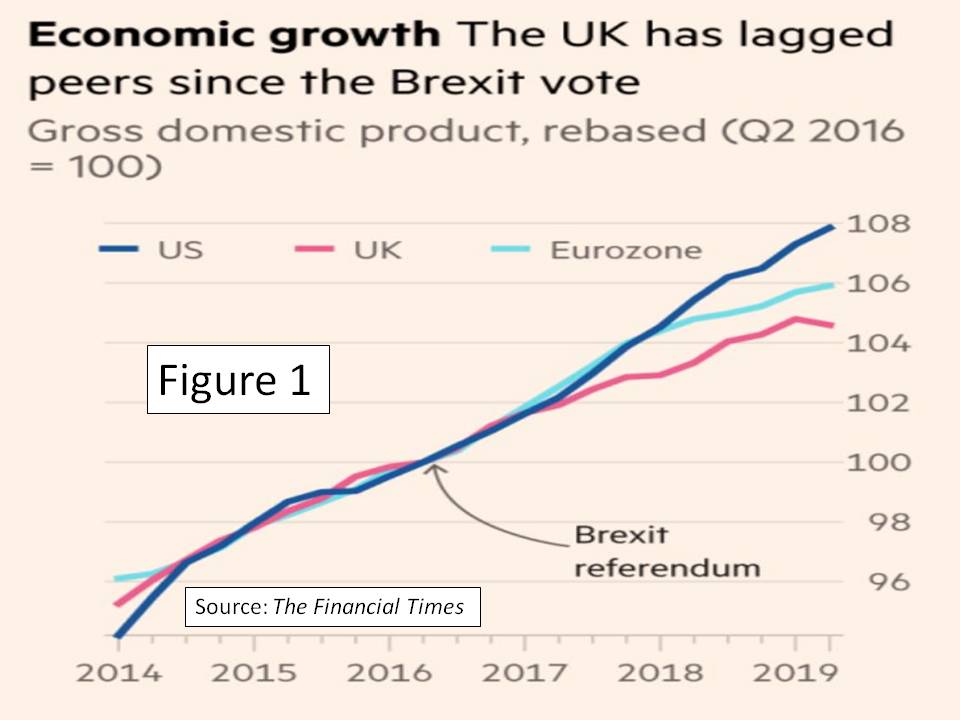

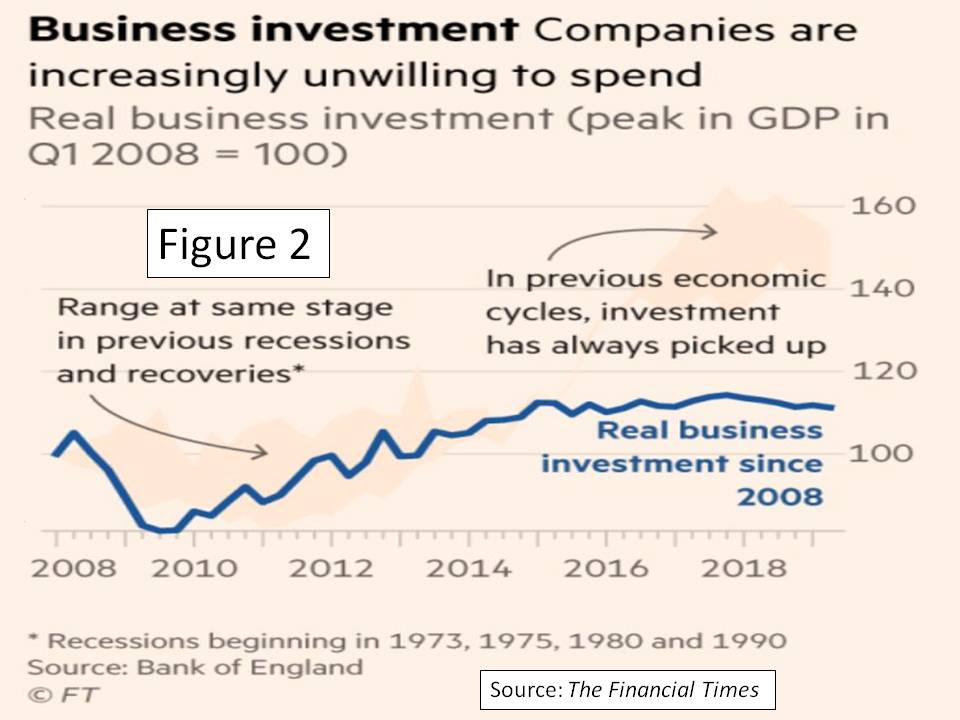

The Financial Times (Figure 1) shows how UK GDP has lagged behind those of the USA and the Eurozone since the 2016 Referendum. In particular, The Financial Times (Figure 2) shows how business investment has stagnated, seriously damaging long-term prospects for the economy.

However, it is simplistic to attribute all the differences in growth and investment between the UK and its competitors to the anticipation of Brexit. Many other events and factors are relevant for this relatively poor performance.

That is why we should turn to the analyses that use official and other models of macroeconomic behaviour, to tease out the different effects. This requires assumptions about governments’ policies, world oil prices, etc. and a range of scenarios as to what might happen.

Johnson’s Withdrawal Agreement

Prime Minister Johnson has negotiated a short-term 11-month deal to December 2020, the Withdrawal Agreement (WA).

Astonishingly, the details of the Agreement reveal that it divides the UK’s internal Customs Union and Single Market by creating a trade barrier down the Irish Sea, something Prime Minister May refused to do to preserve the union.

This is an extraordinary and retrograde development for a modern economy.

However, the long-term outlook remains very uncertain. A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU is a clear possibility depending on the outcome of the December 2019 election.

An EU-FTA may prove impossible to negotiate in the 11 months proposed. Yet, Johnson has committed himself to this deadline, despite his Department for Exiting the EU warning that this risks a disorderly Brexit, according to a leaked official paper.

In this case, unless an extension to the Withdrawal Agreement is proposed by Johnson (he denies repeatedly that he will do so), there will be a chaotic no-deal at the end of 2020.

No-deal is the subject of the second blog in this series.

The economic effects of Johnson’s Withdrawal Agreement from econometric models

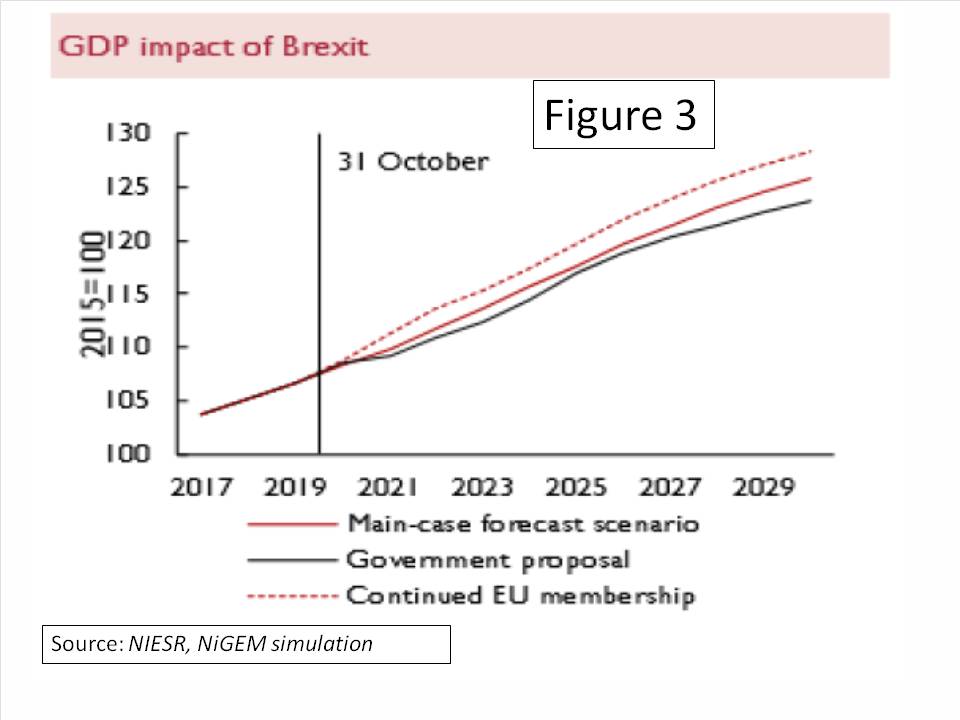

The effects of Johnson’s deal have been assessed by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) in their October forecast. Most of the GDP costs occur in the first two years for the FTA, 2021 and 2022, the long-term cost being about 3.5% of GDP.

The projections by HM Treasury and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) paint a similar picture with long-term growth hardly affected by the deal.

The main problem with these projections (and there are others) is that they are based on neoclassical theory, with its assumptions of representative agents, general equilibrium, constant returns to scale, etc., which bias the results.

For example, the effects they report on long-term growth may be optimistic, because they are influenced by (1) the return to equilibrium built into the models and (2) their assumption that the long-term growth of productivity is largely unaffected by the reduction of international trade.

The econometric evidence suggests otherwise. Productivity is affected by trade, although the relationship is complex.

In what follows, assume the EU-FTA is negotiated in a few months rather than years, and later FTAs with the USA and China take 5-8 years as normal. What does such an EU-FTA mean for the British economy over the 2020s?

UK’s international trade

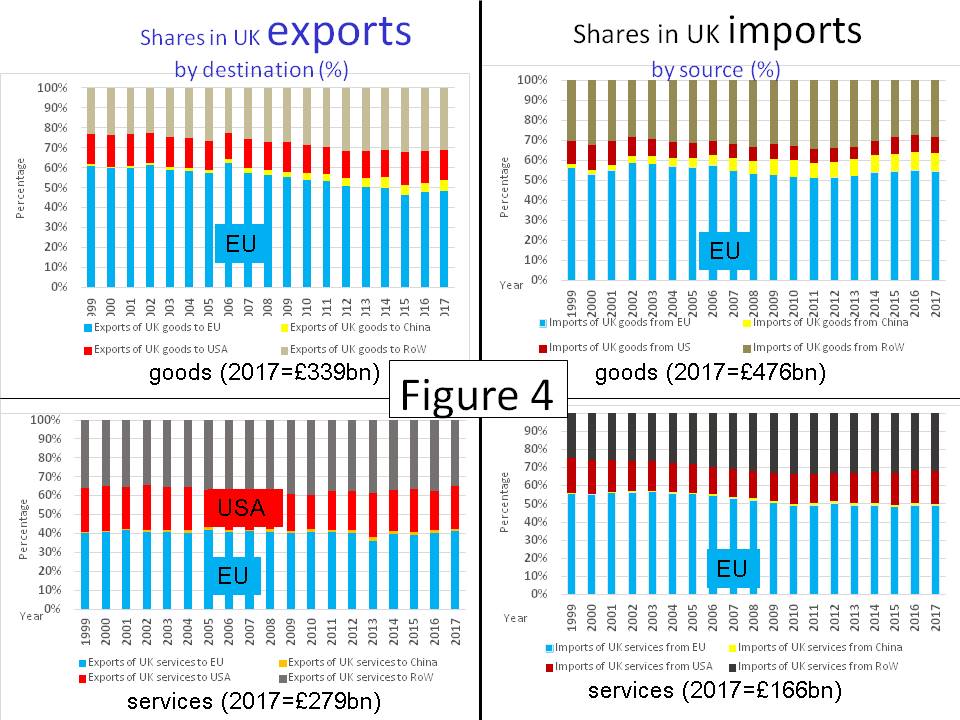

Starting with some facts on the UK’s international trade, Figure 4 shows where our exports go to, and where our imports come from, divided into goods (the top two panels) and services.

The shares are by value and the totals for all exports roughly equal those for all imports, because the UK needs exports to pay for the imports.

The picture is complicated by capital flows, but by and large if there is a long-term fall in export values, the £ exchange rate will fall and, eventually, exports will rise, imports will fall, and balance will be restored.

Within each category, there is substantial and growing two-way (intra-industry) trade, and this feature is evident even as the categories become specialised, particularly in manufactures. This is the supply-chain phenomenon and it is a crucial feature of modern industry.

The European Single Market has fostered and encouraged these chains over the last 40 years, and it was the sudden breaking of them that was a major risk in a no-deal Brexit.

Figure 4 shows that about 44% of all UK goods exports (including manufactures), and about 40% of UK services, are to the rest of the EU. It is these that are mainly affected.

However, overall compared to most other EU countries, the UK clearly specialises in exports of services.

Prospects after an EU-FTA

Despite Government claims, an EU-FTA is not an opportunity for increasing trade relative to that of EU Membership; it risks a “race to the bottom” in terms of weakening standards for food hygiene, human and animal health, and environmental standards, compared to the strong safeguards provided by the EU, compared to those suffered by the US consumer.

In expert opinion, “Many businesses would find adapting to a new FTA just as troublesome as if the UK had crashed out without a deal.” Sam Lowe, Centre for European Reform, 5 November 2019.

Lowe goes on “At its most expansive, an FTA between the EU and UK could remove tariffs and quotas on all goods traded between the two territories.

However, fully tariff and quota-free trade will be dependent on the UK complying with EU-level-playing-field demands on state aid, the environment and labour rights that go beyond what the EU would normally ask of an FTA partner.”

The reason for this is the threat of a loosening/changing of regulations in order to secure later FTAs with the USA or China.

An EU-FTA would also involve much more administration for traders. Even zero tariffs require form filling. And exporters to the EU (over 40% of our total international trade at present!) must prove that they have sufficient local UK content: they cannot avoid tariffs from third countries, just by re-badging imports.

Thus an EU-FTA (especially one negotiated under time pressure with a more powerful and experienced EU team) may require the UK to abide by EU regulations in areas such as pharmaceuticals, food and agriculture, which will then preclude the UK making a wide-ranging FTA with the USA.

The UK will be forced indefinitely to adopt EU regulations with no direct say in their generation or governance, a similar “vassal state” to that claimed for “Brexit In Name Only” (BINO), the much better option of staying in the Single Market and Customs Union after Brexit.

Prospects for service exports after an EU-FTA

However, an EU-FTA is likely to have a much more damaging effect on UK long-term incomes and employment that just more form-filling.

The UK is “services-oriented” in its international trade, exporting far more services to the EU than it imports from the EU. Regulations and standards are especially important for services, and an FTA will not protect UK exporters from new discrimination due to local EU regulations.

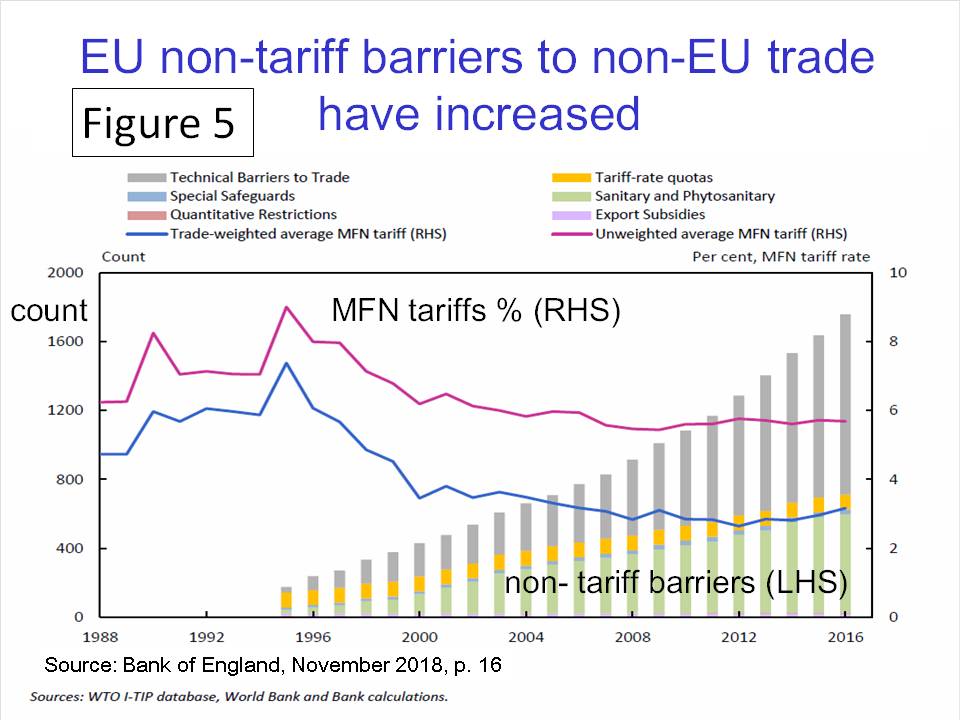

Figure 5 shows how much important non-tariff barriers have become for the EU.

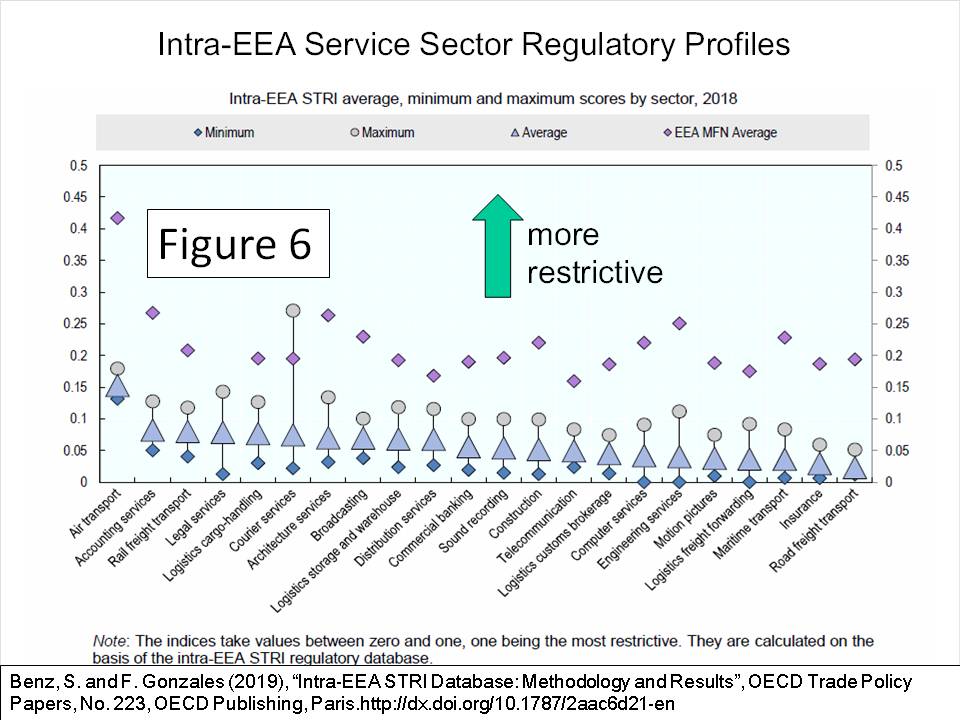

Figure 6 shows the substantial restrictions of services trade from “Most Favoured Nations” (MFNs) than for services trade with other EU Member States.

As a third country, the UK would be one of those MFNs and face these greater restrictions on its service exports.

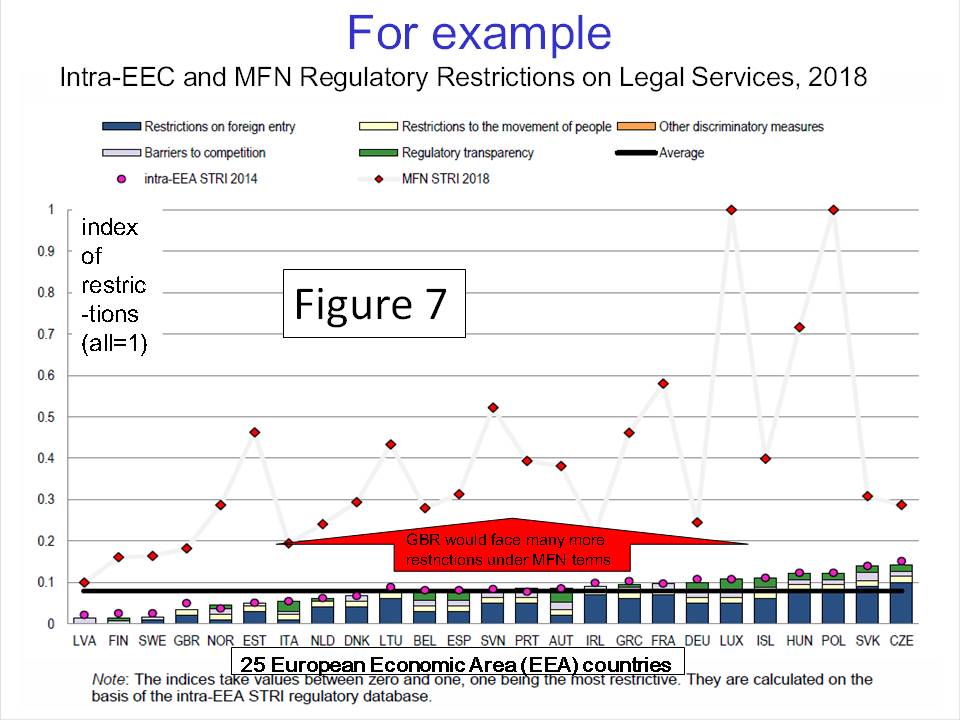

For example, Figure 7 shows how exports of legal services for MFN countries are seriously disadvantaged in many EU states. 40% of UK service exports are to the rest of the EU and, with Brexit these will increasingly become unviable as third-country restrictions are imposed under pressure from local EU suppliers.

Other UK service industries that export to the EU will face restrictions appropriate to their own trade.

Conclusion: cave-in or betrayal?

In conclusion, if Johnson’s plans for UK international trade work out on the most favourable assumptions, then the long-term outlook for the economy looks dire, unless he agrees to all of the EU’s requirements.

Maybe that is what Johnson has in mind, but if so he will have completely betrayed his Brexit followers. In this, of course, he has form – just listen to Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party.

Without another Johnson cave-in, the EU-FTA deal will not be much better for the economy than the no-deal Brexit, except for the legal, administrative and economic chaos that will follow in January 2021.

The long-term prospects after no-deal are the topic of the second blog.

Biographical details

Terry is the Founder of Cambridge Econometrics and the Cambridge Trust for New Thinking in Economics. He developed a new theory of international trade, the “variety hypothesis”, for his PhD thesis, published in 1977 in the Cambridge Journal of Economics as “International trade and economic growth: an alternative to the neoclassical approach“. He has been researching in the area of international trade theory and its application in macroeconomics on and off every since. In March 2019 he presented on “Trade and Development: why a “no deal” Brexit would be an economic catastrophe” in the St Catherine’s Political Economy seminar series.