The centre of Obuse is small: a cluster of a dozen shops amid the myriad chestnut fields, with a brewery selling sake and an open square around the edges of which it is possible to buy every kind of chestnut confectionery imaginable. And it is here, in the hush of the middle of almost nowhere, in the cool hills of Nagano prefecture, 150 miles north-west of Tokyo, that the work of Japan’s most prodigious artist has been collected, in the Hokusai Museum.

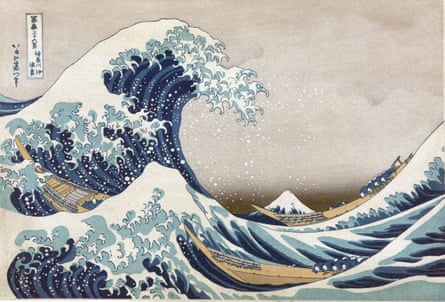

During his life, Katsushika Hokusai, painter of Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa, is thought to have produced 30,000 woodcuts and paintings, and much of his most famous work was not begun until he was in his 70s. In 1844, towards the end of his life, Hokusai came to Obuse, to retreat, and to paint.

The museum is small but worth the journey; worth the half-day train from Tokyo and worth the flight from London. In one of the early woodblock images, A Plum Tree and Two Beauties (1799), two geishas stand, shoulder to shoulder, looking at a point in the distance. One is slipping a note into the other’s sleeve; their faces just barely acknowledge the pleasure of a shared secret. I have never coveted anything so much in my life.

I had longed to see Japan since I was a child; to see the art, and the intricate construction of the wooden temples, and the mountains. I was collected from Tokyo airport by a driver carrying a sign with my full name on it, which is an unnecessarily long one. He pointed at the sign, and then at me. “Only one?” I explained apologetically that it was only me; even my name felt a little excessive and ungainly, and this was to be, it turned out, a running theme; I have rarely felt so uncouth, nor been so kindly treated despite it.

On my first morning in Tokyo, I walked to the Tsukiji fish market, to watch men fillet a tuna head as large as a football in less than 100 seconds. Around the market was a cross-hatching of narrow streets with stalls selling fresh produce, yakitori – charcoal-grilled chicken on skewers – and hot tamagoyaki, a sweet rolled omelette. Food was largely London prices, except for the fruit, which was priced to suit the budget of a vegan Croesus. Single peaches sat, shining like spoiled monarchs, on beds of shredded paper at £7 each. I passed a £15 watermelon, which felt like a lot, until I saw a punnet of £30 strawberries.

I have always taken the attitude that you must eat everything you’re offered once, because there’s always a chance that it will be a revelation. People wouldn’t sell a thing, I tell myself, if it wasn’t at least slightly delicious. It is for this reason that I have eaten tarantulas, tuna fish iced buns, and now, in Tokyo, fish bones crisps – which, I hoped, might be a beautiful and well-kept secret, but in fact tasted of sugar syrup and fish bones.

But the rest of the food was a delight, unparalleled by any city I have known. The late, great Anthony Bourdain said that if he had to eat all the rest of his meals in one city, it would be Tokyo. At night, the streets next to the fish market are dark and empty, but unadorned white light pours from bare bulbs swinging outside a handful of sushi restaurants. I tucked into sashimi fresh from the market; on fish that tasted of butter, of iron, of the sea.

What I really wanted, though, was Fuji. In Hokusai’s 36 Views of Mount Fuji, the mountain is sometimes central, but more often incidental, a jagged inverted V in the background as men and women go about their business, rowing boats, flying kites, carrying heavy loads. Hokusai was a painter of the ukiyo-e genre – this roughly translates as “images of the floating world” – and Hokusai’s was a world alive and incessantly in motion.

My first view of the mountain came from the window of the shinkansen bullet train from Tokyo to Kyoto. The trains are an adventure in themselves; painted white and blue, they have the long noses of purposeful anteaters, and travel at 200mph, with an annual average delay of only 54 seconds per train. We passed rice fields brushing up against bungalows and rickety hotels; and suddenly, emerging from the clouds like an idea being born, Mount Fuji – grey-white shading to white-blue at the top. It was Hokusai’s Fuji; a mountain watching in stillness over a buoyant, moving world.

In Kyoto, there is old Japan. I went to the Kinkaku-ji Buddhist temple, the upper floors of which are completely covered in gold leaf; it shines, casting light down on to the lake that surrounds it and receiving it back again. Equally beautiful, though louder and more frenetic, is the Kiyomizu-dera temple; nearby are stores renting kimonos, and scores of young Japanese women and men dress up for the day in sky shades of silk and posing outside the temple, flashing V signs at the camera.

It is possible, if you are immensely rich, to buy paper-thin pottery in the long winding street at the bottom of the temple’s hill. I am not immensely rich so, after helplessly adoring rice bowls glazed in jewel-blue and jewel-black, I went to the Raku museum. Raku pottery still uses the hand-moulded technique devised in the 16th century; both the name and the style have passed down the Raku family to the current, 15th generation, and the bowls are cut and kneaded, rather than spun.

At the Kyoto Imperial Palace, which is not a single building but several, set in riotously beautiful gardens, I inspected a gravelled Kemari ground, where emperors once watched a game in which players kick a ball to each other, trying to keep it off the ground for as long as possible while dressed in bright carnival colours. The interior walls nearby were painted with images of Kyokusui, a party held along a winding stream, at which each participant must make up a poem before a wine cup was floated down to them on the water. Football then, for the emperors, was cooperative, and poetry competitive. I would have fared better at school, I think, if it had used the same reckoning.

In a bid to follow in Hokusai’s footsteps, I went onwards and upwards, into the Hakone hills, where, in good weather, Fuji can be seen. The clouds were low and thick enough to walk through, so Fuji stood invisible, but I hiked through forests, in thick wet heat, and passed small shrines every kilometre or so, some with offerings of Oreos and potato crisps. There were, too, statues of small human figures, eroded by rain and wind, but wearing freshly laundered red bibs. These are depictions of Ojizo-san, the Japanese deity who is a guardian of children who die before their parents; the bibs are offerings, placed, I was told, in the hope that Ojizo-san will protect the lost child.

Also in the hills, unexpectedly, are vending machines, shaded by trees and surrounded by moss and rocks, branches blowing in the rain and scratching against the clear Perspex front. Enticed by the name, I bought a bottle of Pocari Sweat. It tasted like electrolytes, which I expected, and sweat, which I did not, though I can’t claim I was not forewarned.

My final day in Japan was spent at a glamping site on Lake Kawaguchiko. There, after a fit of torrential rain, the sky cleared, and Mount Fuji stood, looking close enough to touch in bold sunlight, with smoke swirls of cloud scudding across it. It evoked one of Hokusai’s last images, The Dragon of Smoke Escaping from Mount Fuji (1849). In it, a dragon, surrounded by a cloud of silvery-black smoke, twists upwards to the sky. It’s an astonishing thing; a painting that could be of death, or of triumph, or both.

On his deathbed, Hokusai is said to have exclaimed: “If only heaven will give me just another 10 years… Just five more years, then I could become a real painter.”

Hokusai knew though, that already his art had come up against the very edge of being alive. He wrote, in his last days: “I perceive that my characters, my animals, my insects and fish seem to be escaping from the paper. Is that not extraordinary?”

The trip was provided by Inside Japan. Its Hokusai’s Wave Trip – four nights in Tokyo, two in Obuse and two at Mount Fuji – costs from £2,305pp, including ryokan stays, breakfast, some other meals, transfers and private guiding but not flights. At Fuji Hoshinoya, rooms start from 45,000 yen per night hoshinoya.com/fuji/en/. The company’s new 15-night Through the Floating World itinerary is a specially designed Hokusai trail, costing £4,400pp, excluding flights

Masters of Japanese prints: Hokusai and Hiroshige Landscapes is showing at Bristol Museum and Art Gallery until 6 Jan 2019

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion