Inflammatory Bowel Disorders: Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis According to the Mismatch Hypothesis (part 1)

The prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disorders (IBD) is rising worldwide, with three million people afflicted in the U.S. [1] That’s about one in 117. These disorders can cause symptoms of diarrhea, constipation, pain, and extra-intestinal symptoms like weight-loss and anemia. In the most severe, untreated cases, deadly systemic infections (sepsis) can occur.

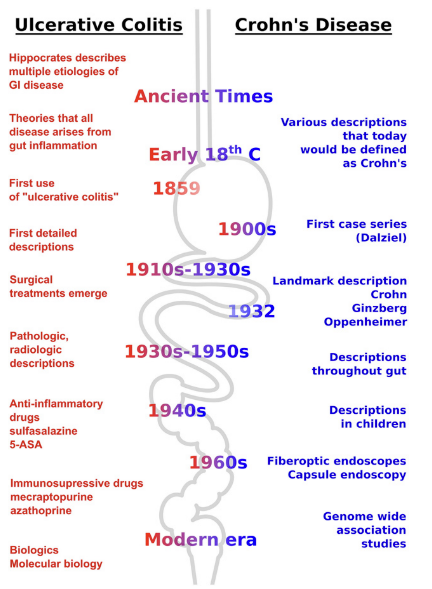

The main manifestations of IBD are Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). They appear recently on the evolutionary timescale, with UC first described in the medical literature around 1850 and CD in 1932 by Dr. Burrill Bernard Crohn. [2]

Autopsies from the early 17th century, however, suggest IBD was already present. (See below)

Genetic changes are too slow to account for the rapidly increasing prevalence of IBD, leaving some yet undiscovered environmental factors as the drivers. As for other diseases of civilization like diabetes and obesity, IBD can be explored through the lens of a mismatch: At what level is the mismatch between our genetics and modern lifestyles occurring? Diet? Antibiotics? Sun exposure? A mix of factors?

The medical origin (etiology) of IBD remains a mystery. This set of disorders is considered chronic and progressive, despite the fact that spontaneous remissions aren’t all that uncommon. There are clinical anecdotes and some trial level evidence which, together, suggest that the supposedly chronic and progressive nature of IBD need not be so.

CD and UC are inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD) whose worldwide prevalence is increasing, now affecting one in 117 Americans. Some yet to be identified environmental factor(s) may be driving it.

IBD: The Umbrella Term

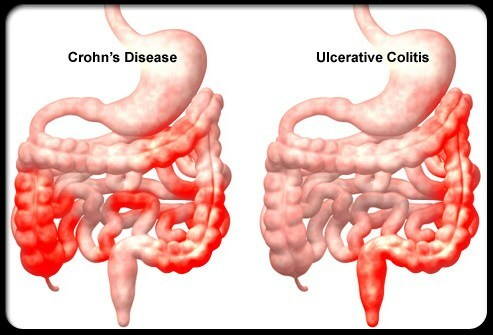

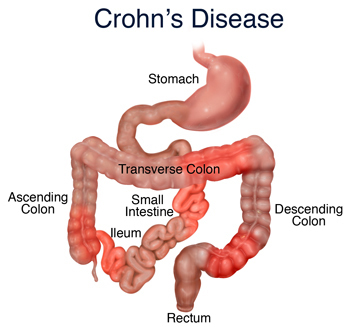

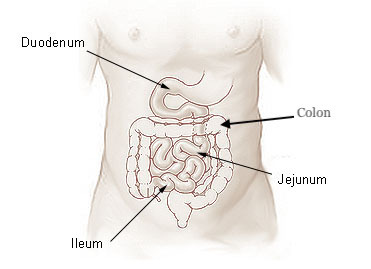

In essence, UC and CD are IBD that manifest in different locations of the digestive system.

However, what’s not seen is CD disease activity disappear, say from the ileum, and only reappear in the colon (as UC)

Where in your digestive system IBD manifests and at what age tells you much more about how it likely developed than your genetics could. [4]

For example, as noted in a recent study by Torres et al., “27 to 54 percent of patients with proctitis or left colitis”—meaning those with an inflamed lining of the anus or UC appearing from the anus to the left descending colon, respectively—“will show some proximal disease extension during the course of their disease” [5].

This observation contributed to the following proposal for an expanded classification of IBD: ileal Crohn’s disease (only in the ileum), colonic Crohn’s disease (in the ileum and colon), and ulcerative colitis (only in the colon).

Where IBD occurs in the digestive system and at what age are better predictors of symptoms and how severely the disease may evolve, compared to genetic markers. A triple categorization of IBD according to where it occurs may be preferable to the dual UC-CD distinction.

A Venn Diagram of Symptoms

Anti-inflammatory drugs like prednisone and methotrexate are given as first-line therapies for patients with IBD in order to quell inflammation-induced damage happening in the digestive system.

This speaks to the major inflammatory component of the disorder. Depending on where, and the extent to which, the digestive tract is inflamed, this can lead to dysmotility and thus constipation and/or diarrhea.

CD, because it affects the small intestine where we absorb much of our nutrients and energy, can lead to weight loss and poor nutritional status. UC, because it affects the colon which normally ferments plant fibers or animal skin and cartilage, typically leads these to show up undigested in stool.

Bloody stools aren’t uncommon in IBD, especially in mild-to-moderate UC and proctitis. The closer to the anus the disease activity occurs, the higher the odds are of seeing blood in stools.

Bleeding can translate to anemia, and low hemoglobin and hematocrit levels on blood tests. Anemia is the loss of iron, hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying molecule, and hematocrit levels tell you the percentage of red blood cells (carrying hemoglobin) in a volume of blood.

Extraintestinal symptoms common to both diseases manifest in the skin, joints, and eyes. In UC the biliary tract is affected, and in CD it’s also visible in the bones, kidneys, and liver. The separation of symptoms isn’t necessarily distinct. As an example of these extraintestinal symptoms, parts of the eye can become inflamed like the eyelids (blepharitis) and uvea (uveitis).

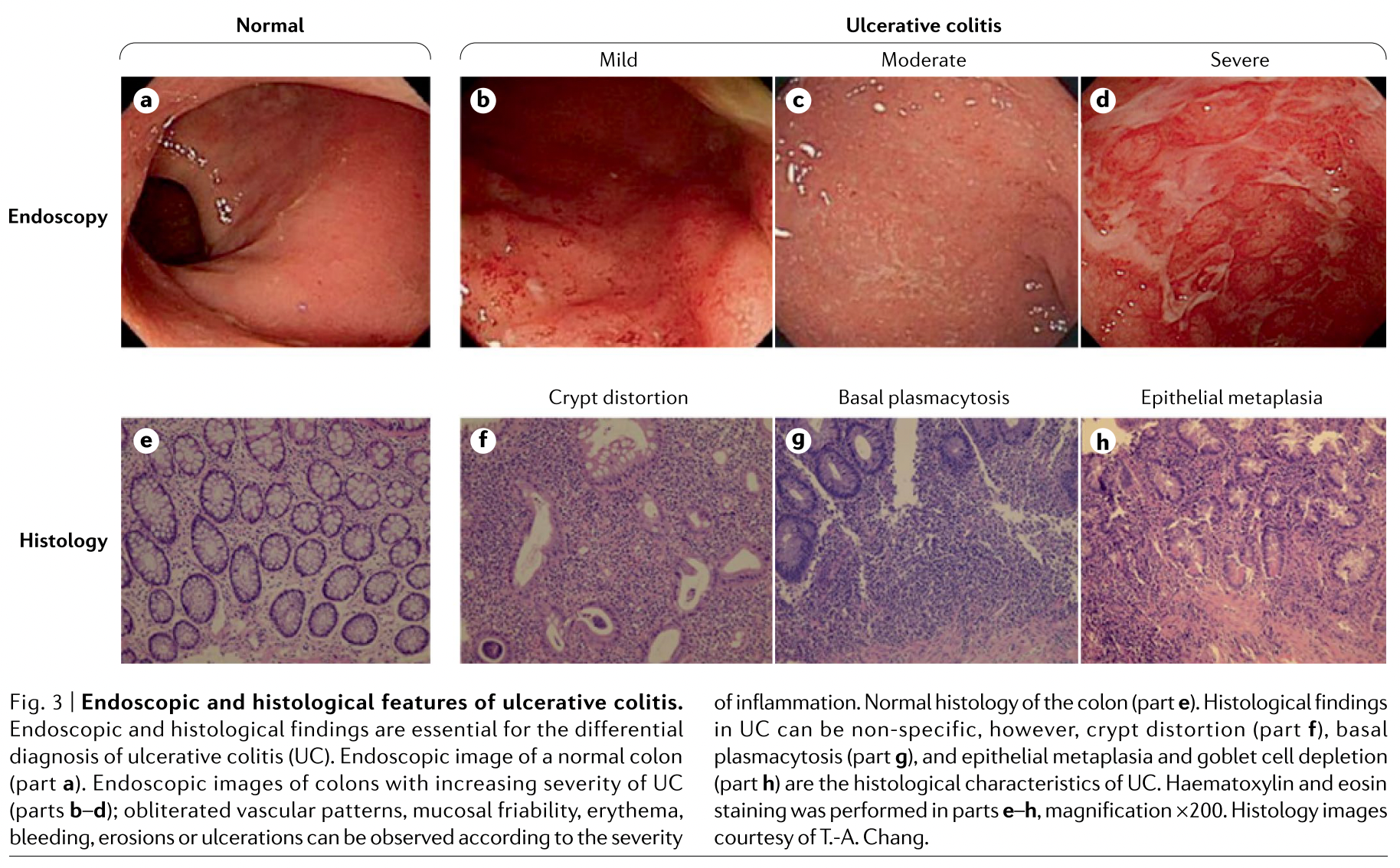

The colonoscopy images below compare normal colons to UC colons with different grades (mild, moderate, severe) of damage (crypt distortion, basal plasmacytosis, and epithelial metaplasia) to the mucosal barrier (mucosa and submucosa). [6]

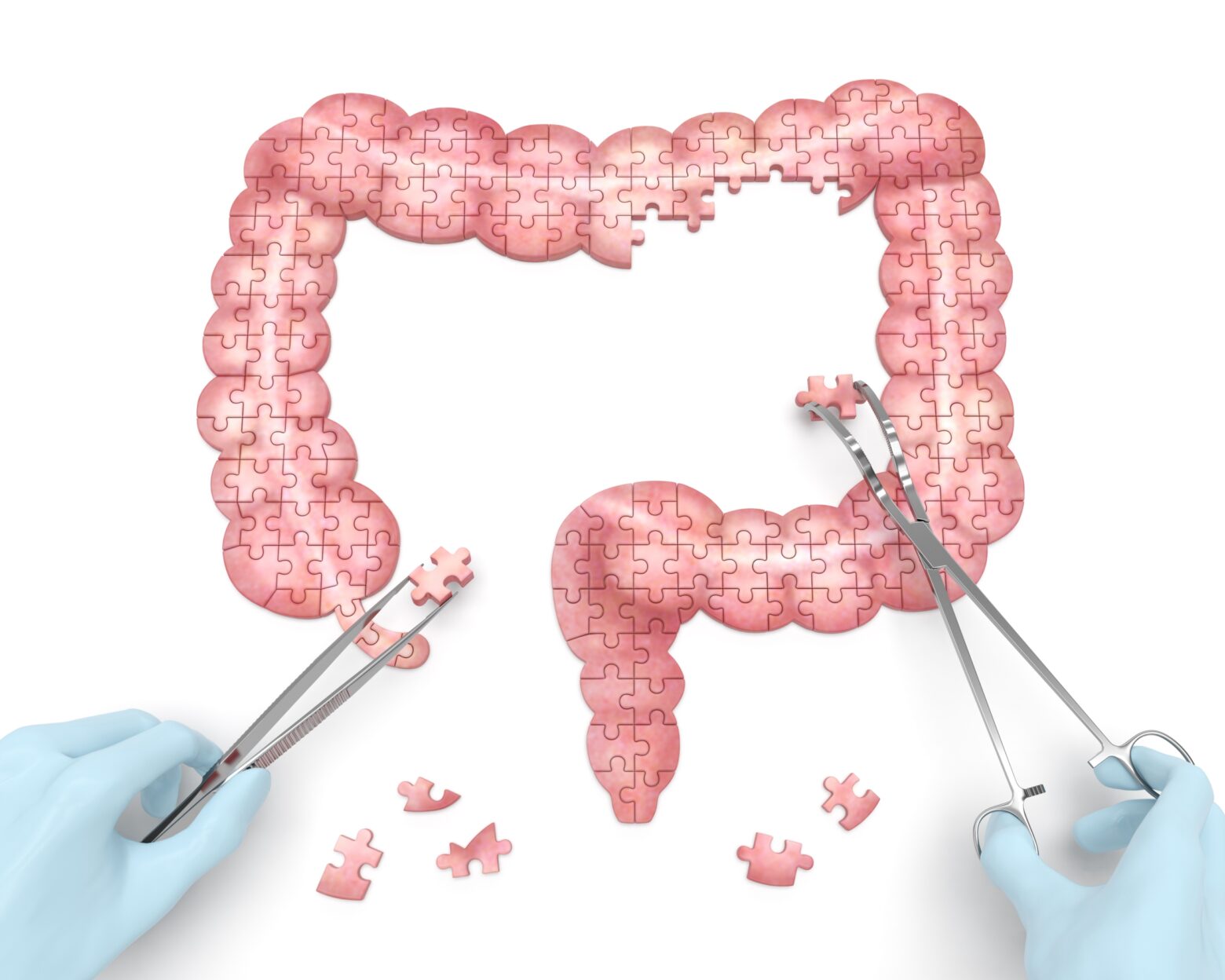

Continuous areas of inflammation and pseudopolyps are present. If the damage is sufficiently pronounced, the colon may be removed via a colectomy.

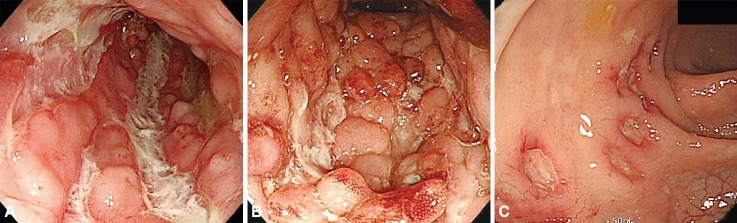

The endoscopic images below show prominent ulcerations (the white material) and ‘cobble-stoning’ characterizing severe CD. [7] Crohn’s occurs transmurally, deeper than the mucosal barrier. Narrowed segments of the digestive tract (strictures) can occur.

Going from the upper to the lower part of the digestive system, only five percent of people with CD see disease activity in the gastroduodenal region only, 32 percent in the small bowel only, 35 percent in the ileum and colon, and 32 percent in the colon only (which some will classify as UC). [8] Segments of the intestine are sometimes removed to stop inflammatory flares from spreading and leading to severe infections.

Etiology

If inflammation is the proximate cause of the damage, what’s causing this destructive inflammation in IBD? Is it different in CD and UC? It could be the microbiota. Its density is greater in patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease than in healthy control subjects. [9]

But whether or not these are reproducible, disease-specific alterations has not yet been tested. One may think that killing an excess of microbes with antibiotics might help, but side-effects often outweigh any of the modest benefits. [10]

Maybe non-organic factors are destroying the mucosal barrier. The mucosal barrier is susceptible to emulsifiers, such as those used in processed food. Even detergents like dish soap may damage the barrier. This can lead to an increase in bacterial translocation [11] and thus an immune response that may further damage tissue. This strengthens suspicions about bacteria living in our mucosal barriers being involved in IBD.

Other factors like vitamin D and latitude correlate to IBD severity [12] and prevalence, respectively. Indeed, ”impaired VDR [vitamin D receptor] signaling might worsen colitis through multiple effects, and vitamin D supplementation has been reported to increase both bacterial richness and diversity in favor of [beneficial] butyrate-producing microbiota.” [13]

Furthermore, “in a population of U.S. women, increasing latitude of residence was associated with a higher incidence of CD and UC,” with those from southern latitudes showing a reduced hazard ratio for CD [0.48 (95% CI 0.30 to 0.77)] and UC [0.62 (95% CI 0.42 to 0.90)]. [14]

Although all of these factors are potential levers to manage the disease, whether with medication or lifestyle changes, it’s still unclear what really causes IBD. As mentioned before, genetics don’t offer a compelling explanation either.

Genetics can’t explain the origin of IBD but gut microbes are a prime candidate (despite antibiotic treatment not curing it). Living in a southern latitude, maintaining adequate vitamin D levels, and avoiding emulsifiers and detergents is likely helpful for IBD patients.

IBD mostly affects the digestive system through an inflammatory response causing damage to the tissue. The medical origin of this disorder remains unknown. Its prevalence is growing worldwide. Genetics is a poor predictor of who gets these disorders and how they may evolve. Where the disease manifests in the digestive system and at what age are better predictors.

In part 2, we will discuss diet as a major lifestyle intervention. We’ll also analyze the pharmaceutical landscape. Understanding which interventions are currently the most effective and which ones on the horizon appear promising will help us better understand the possible origins of this disorder and thus solve our mismatch mystery.

References

[1] Dahlhamer J, Zammitti E, Ward B, Wheaton A, Croft J. Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2015 [Internet]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27787492/

[2] Mulder D, Noble A, Justinich C, Duffin J. A tale of two diseases: The history of inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. https://academic.oup.com. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ecco-jcc/article/8/5/341/616781

[3] Pearce J. Sir Samuel Wilks (1824–1911): ‘The Most Philosophical of English Physicians’ [Internet]. https://www.karger.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/180315

[4] Cleynen I, Boucher G, Jostins L, Schumm L, Zeissig S, Ahmad T et al. Inherited determinants of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis phenotypes: a genetic association study [Internet]. https://www.thelancet.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)00465-1/fulltext

[5] Torres J, Billioud V, Sachar D, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel J. Ulcerative Colitis as A Progressive Disease: The Forgotten Evidence [Internet]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22162423/

[6] Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, Wei S, Ferrante M, Shen B et al. Ulcerative colitis [Internet]. www.nature.com. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-020-0205-x

[7] Lee J, Lee K. Endoscopic Diagnosis and Differentiation of Inflammatory Bowel Disease [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4977735/

[8] Baumgart D, Sandborn W. Crohn’s disease [Internet]. https://www.thelancet.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(12)60026-9/fulltext

[9] Sartor R. Microbial Influences in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases [Internet]. https://www.sciencedirect.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0016508507021579?via%3Dihub

[10] Nitzan, Elias, Peretz, Saliba. Role of antibiotics for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. www.europepmc.org. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4716021

[11] Merga, Campbell, Rhodes. Development, validation and implementation of an in vitro model for the study of metabolic and immune function in normal and inflamed human colonic epithelium [Internet]. https://www.karger.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/358156

[12] Karimi S, Tabataba-vakili S, Yari Z, Alborzi F, Hedayati M, Ebrahimi-Daryani N et al. The effects of two vitamin D regimens on ulcerative colitis activity index, quality of life and oxidant/anti-oxidant status [Internet]. https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://nutritionj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12937-019-0441-7

[13] Nielsen O, Hansen T, Gubatan J, Jensen K, Rejnmark L. Managing vitamin D deficiency in inflammatory bowel disease [Internet]. https://fg.bmj.com/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://fg.bmj.com/content/10/4/394

[14] Khalili H, Huang E, Ananthakrishnan A, Higuchi L, Richter J, Fuchs C et al. Geographical variation and incidence of inflammatory bowel disease among US women [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/. 2021 [cited 12 January 2021]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3418414/

Raphael Sirtoli, M.Sc.

Raphael Sirtoli has an M.Sc. in molecular biology and is a Ph.D. candidate in health sciences at the Behavioral and Molecular Lab in Portugal. Raphael is also co-founded Nutrita.

More About The Author