We first published this story in 2016, to mark the 20th anniversary of Carolyn Bessette and JFK Jr.'s wedding.

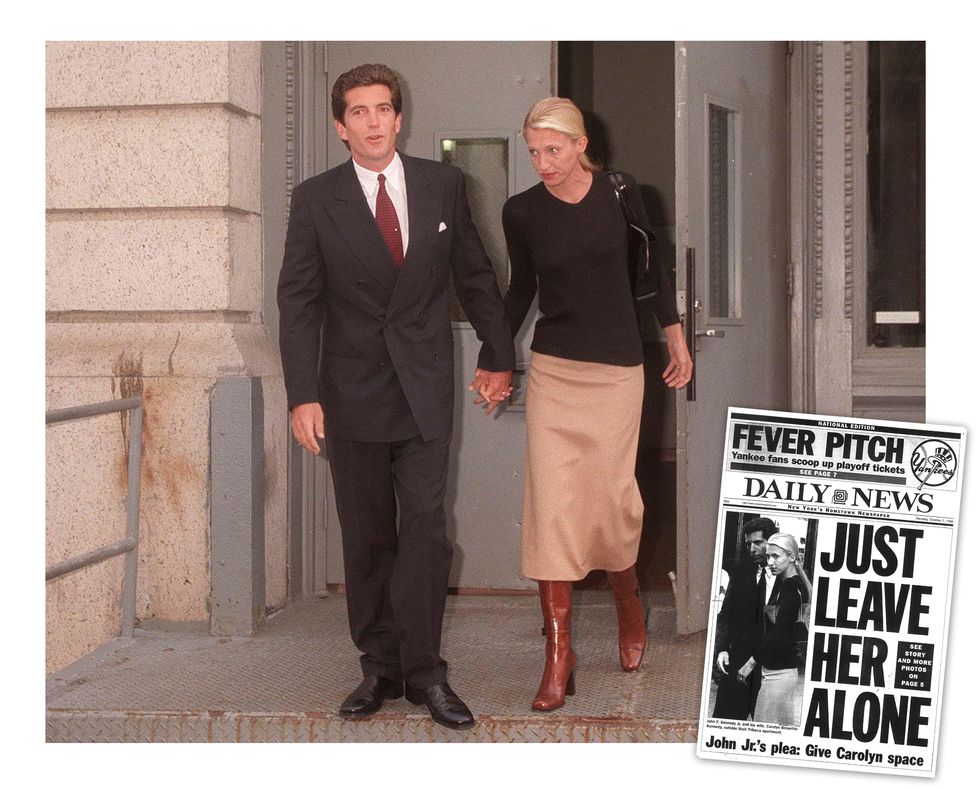

On Sunday October 6, 1996, John F. Kennedy Jr. stepped out onto the stoop of his Tribeca loft at 20 North Moore St. and stopped short. It was a perfect fall morning; most of New York City was either sleeping it off, headed to brunch, or reading the Sunday Times. But Kennedy, so often seen flying down the city's streets on his rollerblades, in shorts and a T shirt, was already formally dressed in a sharply cut dark blue suit and red tie. Below him, a crush of journalists and photographers awaited. He was about to attempt the impossible: make an appeal to their better angels.

Kennedy had already pulled off the impossible fifteen days earlier, when he'd married a woman named Carolyn Bessette in a clandestine ceremony on a tiny island off the coast of Georgia. So few people knew it was happening that when the news broke the next day, many of his family members were caught off guard. On Monday morning, two days after the wedding, a single snapshot of the couple on the steps of the church—Bessette grinning, wearing a Narciso Rodriguez-designed white dress that looked more like a slip than a wedding gown, her face free of makeup; Kennedy kissing her outstretched hand—led news reports around the world.

Now, two weeks later, here was America's beloved son, fresh off his Turkish honeymoon, about to officially introduce his new bride to the world. He hoped to assuage the onslaught of press he'd been exposed to his entire life by facing it head-on. "I just ask," he said, striving for friendliness, his voice barely audible above the cacophony of clicking cameras, "[for] any privacy or room you could give her as she makes that adjustment. It would be greatly appreciated."

Then he turned and disappeared back into the building. A few minutes later the door opened again. This time he emerged with Bessette clutching his hand.

She looked terrified.

This October marks 20 years since Bessette made her debut on those Tribeca steps. Her marriage would last just over 1000 days—almost the exact length of time Kennedy's father served as President—and end when the Piper plane piloted by her husband, carrying her and her older sister Lauren, crashed into the Atlantic Ocean on a hazy July night in 1999.

In the pages of the city tabloids during those few short years, she was a daily soap opera, forced into the multitude of unforgiving tropes for public women. The scheming girlfriend; the coked-up vixen; the miserable spouse. So obsessive was the coverage that I recall one tabloid splitting its front page between the day's top news story and picture of her scooping up the couple's dog Friday's poop from the sidewalk.

Kennedy and Bessette had quietly dated for two years before their wedding, and she had somehow managed to stay out of the media's glare during that time—with one spectacular exception. Six months before they tied the knot, paparazzi filmed the couple fiercely fighting in a New York park. She took off her engagement ring and threw it at him. He burst into tears. These days, that would earn you a million feminist memes or gifs of the give-no-fucks sort. But twenty years ago, women were not rewarded for being feisty. Photographs of the fight were sold to the National Enquirer for a quarter of a million dollars, and tabloid shows aired a blurry video of the whole exchange on repeat for days; it even made it into an SNL sketch that weekend. In the aftermath, Bessette disappeared from view.

"That video was terrible for her, because it framed her as this sort of mean harpy,"says George Rush, who, along with his wife Joanna Malloy, penned the gossip column "Rush & Malloy" for the New York Daily News for 15 years, starting in 1995. "She never recovered from that branding, really."

The furor that followed the release of that tape was a taste of what was to come. After the wedding, everything was up for grabs, up to and including the shape of Carolyn's eyebrows. And unlike today, where stars have enormous control over their public image via social media, at that time there was very little means to push back. Bessette and Kennedy just had to take it.

"They thought that people were going to be interested in the wedding, and if they could pull off the wedding being private, their marriage would not be that interesting," says a college friend of Bessette's who kept in touch with her during her New York years. "She's off the market; business is done; they're going to be private citizens."

"She didn't know it was going to be that intense," says Brad Johns, Carolyn's hairdresser (who would famously reveal to the world that he had endeavored to give Carolyn's naturally light-brown hair "buttery chunks"— he spoke about it so many times, in fact, that he was eventually served a cease-and-desist order by the couple's lawyers.)

Carolyn had arrived on the scene at a time when New York's tabloids wielded a near absolute, now unimaginable, power. One line in "Page Six," the New York Post's infamous gossip page that almost never ran photos, was enough to make or break a career. During her marriage, Carolyn was mentioned near daily.

"The fact that so much of the media was based in New York made the tabloids disproportionately influential," says Rush. And there was no greater catch than John F. Kennedy Jr. "On the celebrity safari, Kennedy was the lion of the big game hunter," says Rush. "[John and Carolyn] never grew old."

The media attention and Kennedy's desire for normalcy became a toxic combination—one that left Bessette little protection. Raised in a life of privilege on the Upper East Side across from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kennedy went to great lengths to live as any other New Yorker, much to the endearment of the city's denizens. In the late nineties I worked at a bar in the Greenwich Village, and remember our cook recounting how Kennedy would sometimes show up at late hours to have a beer and rehash the day's game: "He was a good guy," he'd say. "So normal." The couple's Tribeca building had no doorman; they didn't have private cars or personal drivers. Carolyn navigated the sidewalks each day alone, an increasingly terrifying prospect.

I saw Bessette on the sidewalks of Tribeca a few times back then. The first time she was walking ahead of me, and only caught my attention because she kept looking nervously over her shoulder. Once I realized who she was—in flared jeans, the hem let down, and a cropped black leather jacket; her blonde, blonde hair pouring down her back— it occurred to me she thought I might be chasing her because I was walking so quickly. I crossed the street. She stopped to give some unsuspecting tourists directions before disappearing into a cab. Minutes later, the cab drove past me, Bessette slipped low down in the back seat, her head turned away from the window.

Presumably, Bessette entered the marriage assuming she was well-positioned to handle the coming fury. She'd been a PR exec at Calvin Klein during the height of the designer's power and controversy. New York Daily News reporter Don Kaplan, who was working for DNR, a now-defunct offshoot of the fashion business publication WWD recalls a time he interviewed Klein during Bessette's pre-Kennedy days. "The waiting room outside his office was this white room: white furniture, white walls. Suddenly the door opens and this gorgeous, absolutely gorgeous woman appears. Tall, blonde—she was towering over me."

After leading Kaplan back to Klein's office, Bessette sat in on the interview that followed. At first, says Kaplan, all went fine. It was only when he ventured into questions about Klein's deeply controversial 1995 ad campaign—made infamous by its resemblance to kiddie porn—that the interview quickly went south. "I was like, 'Do you think all of this negative publicity associated with this ad campaign is going to have any impact on the stores sales in the first couple of weeks?' Fair question. He stops dead. Then he smacks the table, hard, and says 'The interview is over.' The next thing I know, she grabs me by my shoulder, stands me up, spins me around, and I'm hustled out of his office."

It's not hard to conclude that Bessette was under the misapprehension that she'd always be able to hustle the press out of her office and her life. When it became apparent she couldn't, she resorted to silence. The woman never spoke in public. She never did a single interview. There are only two recordings of her voice: one eight-second clip from the 1998 Fire and Ice Ball, when Entertainment Tonight briefly caught her departing on the arm of cousin-in-law Bobby Shriver, and a three-second clip, again from Entertainment Tonight, two months before her death, this time on the arm of her husband on the red carpet for the Newman's Own/George Awards ceremony. That's it. She appears to be the last of the Greta Garbos: an extinct breed of fame that understood the power of remove and silence over all else.

The irony is, Kennedy may have been attracted to her in part because of her remove. She managed to capture the elusiveness his mother was so famous for, but brought to the table a civilian upbringing he'd never known. The product of divorced parents, she'd been raised by a no-nonsense school teacher mother in Greenwich, Connecticut. Far from Kennedy's private school, Ivy League world, she'd attended Boston University for childhood education, supporting herself with part-time jobs. "She always worked," says Colleen Curtis, who roomed with Bessette in college. "Always."

In her memoir What Remains, Carole Radziwill, who was married to John's cousin Anthony Radziwill, notes they bonded over both having worked summers at the discount department store Caldors. "We were wearing yellow smocks while you water-skied off the [Onassis yacht] Christina," Radziwill quotes Carolyn as joking to their husbands.

She was also self-made. Every transplanted New Yorker arrives to the city with the desire to become a better version of her or himself. But even Bessette's college crowd would likely have had a hard time aligning the former "fun, curvy party girl," as one fellow classmate put it, with the svelte, sleek Manhattanite she quickly became.

Bessette had arrived in New York at the tail end of the eighties, after being plucked off the floor of a Calvin Klein store in Boston by a company exec. Within five years she went from being the personal shopper to Diane Sawyer and top-tier Upper East Side socialites, to PR executive, to Klein's style inspiration. According to Maureen Callahan's book Champagne Supernovas, we partly have Bessette to thank for our other late twentieth-century muse: Kate Moss. When the unknown waif appeared on Klein's radar, it was Bessette, along with art director Fabien Baron—part of Klein's "new order"—who convinced the uncertain designer that Moss was exactly what he needed. It was a decision that resulted in Moss's legendary shoot with Mark Wahlberg, and largely helped the company survive near-bankruptcy. Bessette and Moss (along with her boyfriend Johnny Depp) would go on to live in the same Village apartment building for a number of years following her Calvin Klein debut.

And then, of course, there were her looks and style, which remain legend. "She was one of the first people who was really followed in the press closely for her fashion on the street," says Kate Betts, a frequent contributor to Town & Country and former editor in chief of Harper's Bazaar. "This was 1996; it was the beginning of paparazzi shooting street style. Dressing celebrities in designer clothes was not as big a deal as it has become. The whole red carpet thing had only just really started."

"She was incredibly, beautiful, but she really didn't photograph that well," says a woman who knew her in New York. "No matter what angle you shot her from. There was something about her that was never really captured by a camera."

"I remember walking into a room and all these guys I'd gone to college with were sitting there, and I was like, 'Are you guys having a conversation about the first time you saw Carolyn Bessette?'" recalls Colleen Curtis. "And they were kind of sheepish, and like 'Yeah.'"

"She was just so cool," television host and stylist Stacy London says, still able to describe— two decades later—exactly what Bessette was wearing when they first met while working on the CK campaign. "A long camel coat, vamp nail polish before anyone else, and her hair perfectly tousled like she'd just gotten out of bed."

Bessette remains a one-woman fashion cult, her style heavily referenced by fashion darlings like The Row. There are websites dedicated to her favorite rumored cosmetics. It's incredible to consider that twenty years of fashion have come and gone since Bessette, and yet photos of her would not be out of place on any recent "Best Dressed" lists. "She dressed like a grown woman, but she didn't look old," says Patricia Mears, deputy director at the Fashion Institute of Technology. "Something that you would have seen back in the '30s, '40s or '50s. People tried to draw an analogy between her and John's mother, Jackie Kennedy—that same sort of elegance. I don't think there is anybody like that anymore. Everything is about social media and how you can attract attention [now]. That was the opposite of what she wanted to do."

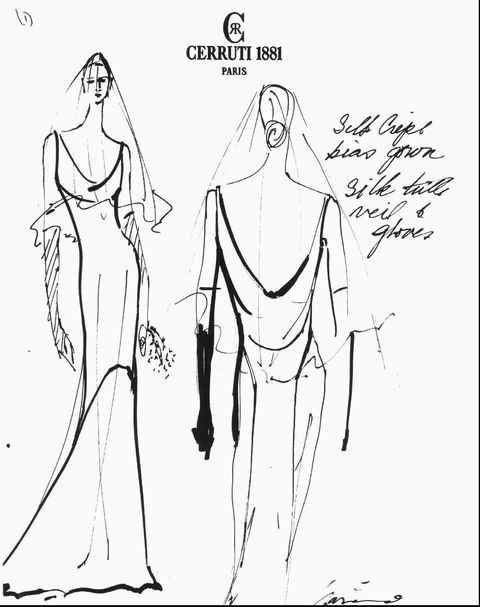

By the time she married Kennedy, she'd left Calvin Klein, and, in what might be translated into a rather chic fuck you, opted to have former Klein designer, close friend, and then-unknown Narciso Rodriguez design her dress.

"The idea of the slip dress as wedding dress for that time was revolutionary," says Betts. "Its simplicity was shocking."

"We're still feeling the impact of that dress," says Molly Guy, creative director of Stone Fox Bride. Her company created its "Lucinda" dress based on Carolyn's gown, she says, because "so many people still refer to themselves as 'the Carolyn Bessette Kennedy bride.' It's our most popular, most-sold style to date."

But not long after her debut in that iconic photo, and on that Tribeca stoop, the punishing attention began to wear Bessette down. She appeared in public less and less. A year or so into the marriage she practically disappeared altogether—a shocking transition for a woman who was described by nearly everyone who knew her as being lively, magnetic, and joyful. Her total silence provided extra room for speculation. Rumors that she was using drugs, that he was cheating, that she was domineering in the offices of John's magazine George, that she was pregnant, she wasn't pregnant but wanted to be—all the usual nonsense flooded various channels.

In Bessette's case, it didn't help matters that after her wedding, when the public was getting to know her, she was rarely photographed smiling. (Never mentioned in the captions was the fact that so many pictures were taken on the street, as she was trying to go about her day.) Even her clothing choices seemed aimed to show as little as possible.

Prior to their marriage, Carolyn was often photographed in the slinkiest of outfits: plunging V-neck and strappy dresses that showed off her extraordinary figure. Afterwards the necklines went up, up, up. When she did appear at official events in public, it was almost exclusively in uncompromising designs of Japanese avant-garde Yohji Yamamoto, her famous luscious hair severely pulled back, almost school-marmish.

What was she doing locked away in that Tribeca loft? Was she a latter-day Miss Havisham in the making? Dreaming of a house and family in outside New York where she could move freely? It's hard to say. After leaving her post at Calvin Klein, she'd shown no interest in returning to work, and didn't appear in the places one usually finds society wives: no charity or museum boards, no foundations. In What Remains, Radziwill documents how Bessette was her main and longtime source of support in caring for her husband as he battled cancer (Anthony Radziwill died three weeks after the plane crash), showing up time and again for doctors' appointments and hospital visits. Beyond that, her lack of visibility suggests she was still struggling mightily with the realities of her new role.

Had she lived, Bessette would have been 50 this year. It's hard not to wonder what she'd be doing. Would she be a fashion editor? A consultant? Started her own pop-up line, a la Kate Moss and Topshop? Surely that excellent taste would not have languished forever.

She was only 33 when she died. Young and mid-transformation into whatever was next, but never arrived.

Edited by Whitney Joiner • Senior photo editor: Jennifer Newman

Glynnis macnicol is a new york city-based writer, speaker, digital media consultant, and podcast editor. She is the author of /No One Tells You This.\