On 12 July 1967, Florida newspaper the St Petersburg Times had an eye-catching front-page headline: “Dame Margot, Nureyev seized in hippie raid.” Police had busted a party in Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco, and unexpectedly ensnared two world-famous gatecrashers: Margot Fonteyn and Rudolf Nureyev, who had been in the city all of four hours. “Marijuana cigarettes were found at the scene,” noted the paper, although the two ballet dancers had to be released as there was no evidence that they had been smoking them. A high-spirited Nureyev had, however, performed a jeté into the back of a police van.

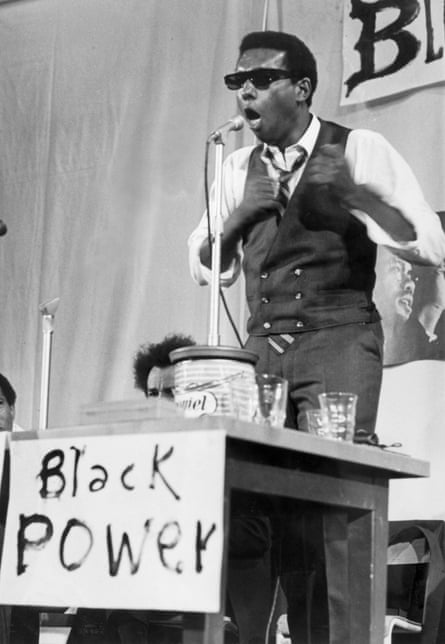

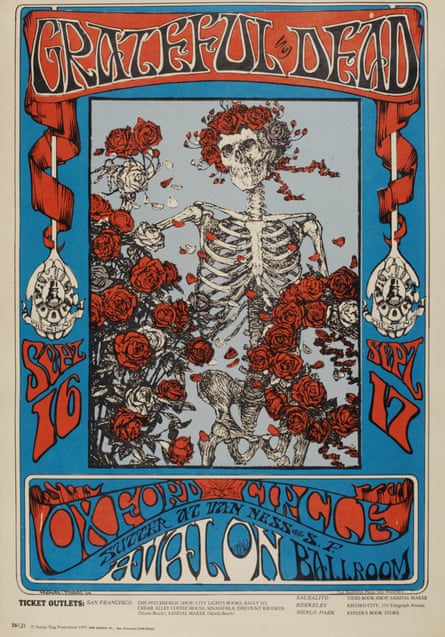

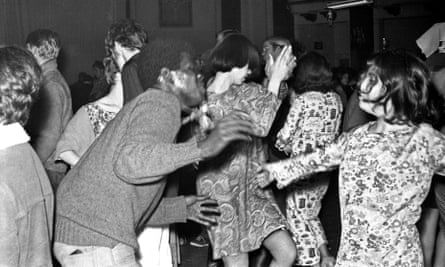

Fonteyn and Nureyev were two of an estimated 100,000 people who descended on San Francisco to locate the action during the drugged-up summer of love. It turned out that everything was happening. There were anti-Vietnam protests on the campus at Berkeley; Oakland’s African-American revolutionary movement, the Black Panthers, marched on the state capitol while openly armed; and bands such as the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and the Holding Company, fronted by Janis Joplin, performed on stage at venues such as the Avalon and the Fillmore, their acid-sodden psychedelia expressing the preoccupations of counterculture from surrealism to sex.

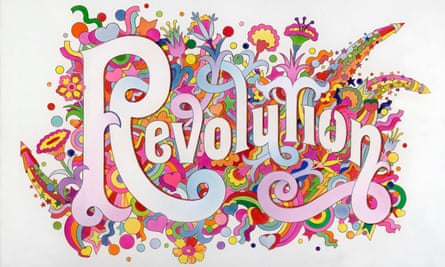

Add performance artists and community activists such as the Diggers – who, freaked out by the weekenders, announced the death of the hippie in October 1967 and staged a mock funeral – to the retina-searing, tripped-out aesthetics of the time on record sleeves, gig posters and in fashion, and you had an unprecedented mass experiment. The subject was the rejection of conventional society with its racism, warfare and repression; and the construction of alternative realities. All this was duly transmitted by an astounded mass media to living rooms around the world, while records such as the Beatles’ 1967 album Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band formed a clarion call for the counterculture on both sides of the Atlantic. Two weeks after its release on 1 June, it was played over the speakers at Monterey Pop, arguably the first music festival.

Then there were those hippies who were heading for the countryside to live communally with a copy of the Whole Earth Catalog, which contained a wealth of information from the best kerosene lamps to which book on goat husbandry to buy. Over at Stanford University, meanwhile, scientists were working on developments in personal computing that would lay the foundations for Silicon Valley and create the future – our present.

It’s a story on a kaleidoscopic scale, and this autumn the Victoria & Albert Museum in London will attempt to tell it through an exhibition. Entitled You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970, the show intends to delineate how the world transformed in those few seismic years, taking in swinging London, the student riots in Paris, and the moon landings – the latter of which were, says co-curator Geoffrey Marsh, “the boldest of human gestures”.

Marsh and fellow co-curator Victoria Broackes created the V&A’s blockbuster David Bowie exhibition in 2013. Like that show, this one promises to use music, objects and images not only to reanimate pop and social history but also to evoke something of the magic and mania of that tumultuous period. It’s also a salutary reminder of the peace, love and understanding that underpinned the hippie ideals – qualities that seem in short supply in 2016.

To create the exhibition, the V&A has gathered objects ranging from Airplane singer Grace Slick’s kaftan to the first computer mouse, and spoken to a host of surviving members of the counterculture.

Over the course of a few days in San Francisco, guided by Broackes, I also meet some of these paradigm-shifting former hippies, and visit the sites of the greatest upheaval.

We go to the steps of the University of California at Berkeley’s Sproul Hall, where Mario Savio, spokesman for the free speech movement, made his astoundingly passionate speech inspiring his fellow students to stage a sit-in and stop “the operation of the machine”. The free speech protests marked a direct link from the civil rights movement, in which Savio had participated, to the anti-war protests that would convulse Berkeley at the end of the 60s; just as the Beatniks of the previous decade, such as Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady, had profoundly influenced the hippies.

We meet Rick Moss, curator at the African American Museum in Oakland, who was 12 when the Black Panthers started galvanising his San Francisco community. “It was very empowering because at no point in your upbringing were you ever given examples of where black people were standing up for themselves,” he says. “So when you see guys swaggering to the state capitol and they’re having their weapons, it’s like The Lone Ranger. We were like: ‘This is great! This is what you do, you stand up to injustice.’”

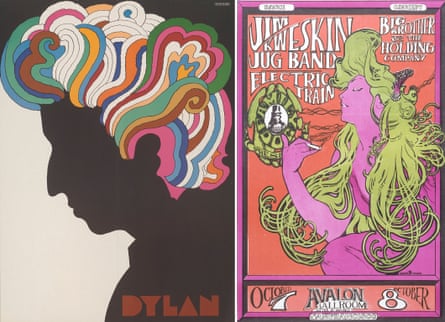

Then there are the artists who defined the aesthetics of psychedelia. One, Joe McHugh, created a Jefferson Airplane-inspired poster called White Rabbit, which depicted a rabbit standing on a chessboard, the words “keep your head” dematerialising in the background. The other, Stanley Miller, known as Mouse, made the skull and roses artwork for the Grateful Dead, although he much preferred hanging out with Janis Joplin. “She was wild,” he remembers, with a glint in his eye. “The first time she came to my studio she chased me around – I was kind of scared of her.”

Music had drawn him from Detroit to California: “It was the Byrds and the Mama and the Papas – that ringing sound, like a siren calling me,” he says, still dreamy at the memory. Like most of the cultural productions of the time, his posters were drug-induced, but he never employed the bulbous lettering and eye-searing hues popular at the time. “A lot of people, how they drew pictures of the psych experience was a lot of colours and mandalas, but to me, [on acid] everything got super-clear.”

Miller later moved to London, where he spent a year working for Nova magazine and hanging out at the Beatles’ Apple headquarters on Savile Row (now a branch of Abercrombie and Fitch). He saw their final concert take place on the building’s roof, without realising that he was witnessing history. He also stopped taking acid that year. “It fell out of fashion. It was replaced in the 70s by a lot of cocaine and I didn’t want to do that.”

The following day, we meet Stewart Brand with his friend and collaborator Lloyd Kahn at his cafe and library within the Long Now Foundation, which is dedicated to his dream of building a clock that will run for 10,000 years. With the aid of some genetic engineers, Brand is also trying to bring back 12 extinct species, and says that he is making real progress on the woolly mammoth: “We use the Asian elephant as a scaffold to assemble the geonome.”

Brand had an intense but limited period of drug experimentation; at 80, Kahn still uses marijuana, although he vapes rather than smokes it. The first time Kahn took acid, he says, “I saw a flower breathing and it wasn’t a hallucination. Flowers do breathe, but you don’t really see it.”

As a biology student at Stanford, Brand first took mescaline when in the army, then became a participant in one of the famous government-sponsored scientific studies of the effects of LSD at Menlo Park, which helped to ignite the 60s drug culture. “The hippie phenomenon was to go and discover how the world works, so all the kids went out with backpacks doing the same thing. And we learned a lot.”

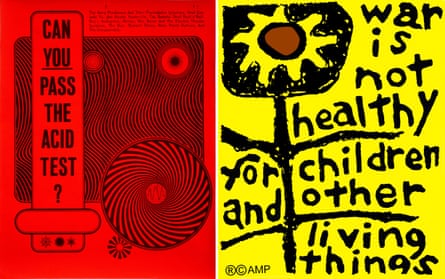

Soon he was travelling to Native American reservations where he engaged in all-night peyote rituals, joining author Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters to stage the acid tests – parties fuelled by LSD that featured light shows, film projections and bands such as the Warlocks (who would later rename themselves the Grateful Dead). “Weird shit would be tried,” notes Brand. The slogan was: “Can you pass the acid test?” – meaning, he says, “Can you make it through the night without being killed or killing anybody?”

Now 77, Brand sees the inquiring and hedonistic spirit of those parties continue at Nevada festival Burning Man, now heavily populated by Silicon Valley workers, “with the enormous difference that we had no money and these guys have money galore. They’ll spend all year building an art car that will stop your heart, just to see it chugging along. Then that feeds back into an anything-goes creativity within the tech companies.”

Brand exemplifies the intersection of the hippie movement and the technological experimentation that built Silicon Valley – the subject of the final room in the V&A’s exhibition. While “full of acid” in 1966, the lifelong conservationist (hence the mammoths) pondered how to get more people caring about the Earth. The architect Buckminster Fuller – whose geodesic dome was displayed in the USA pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal – had made the point “that people think it’s a flat Earth, which makes them think its resources are infinite, and if they just understood it is a sphere, and therefore finite, they would treat everything differently.”

Brand got badges printed that asked: “Why haven’t we seen a photograph of the whole Earth yet?” and the following year an image taken by satellite was released by Nasa. It gave the cover image and title to Brand’s next project, the Whole Earth Catalog, published in the autumn of 1968, biannually until 1972, then sporadically afterwards.

Like many of the originators of San Francisco’s counterculture, Brand had become fed up with the enormous influx of rubberneckers into Haight-Ashbury and, in 1968, headed out to New Mexico and Colorado to participate in the movement to live on communes in America’s vast countryside. Before long, he realised that the communards would need tools, books and ideas, which he decided to collate into a mail-order catalogue. “Whim is the best source,” he says. “The catalogue enables the ability to have a whim and then act upon it, and that’s pretty much my life.”

Brand hands me his copy of the first Whole Earth Catalog, dog-eared and with the dimensions of an oversized magazine (a copy will be in the show).

Purely on a media level, the Whole Earth Catalog has been hugely influential; when the New York Times relaunched its Sunday magazine in February last year, it also had a globe on the cover. The pages inside the catalogue are wonderfully designed, stuffed with information, but never messy or confusing. It wasn’t this, however, that made the catalogue truly groundbreaking. First of all, it was crowdsourced – 40 years before the term became commonplace. Brand appealed for readers to send in suggestions for items that those in communes would find useful (“the customers know best,” he said), paid $10 per item used, and printed the most helpful, making up about a quarter of the overall content. This underlined the fact that the catalogue wasn’t a book so much as a network, where likeminded people could find and share the information they needed to enter and improve alternative worlds. Symbolising this – alongside boots and teepees – the first issue featured Hewlett-Packard’s desktop computer, the 9100A Calculator, then retailing at $4,900.

Brand straddled the worlds of the communes and computers, having become interested in the latter while studying at Stanford, where he filmed the first public demonstration of a computer mouse in 1968. “I was just endlessly impatient for all these things to come into the world, because I’d already seen it – the mouse and online typing, being able to mutually massage something on screen with another person, which even now is kind of difficult … [it was] apparatus to augment the human intellect.”

This reconceptualising of the world as an information network made the catalogue hugely inspiring to a significant handful of local computer scientists. To the most forward-thinking and idealistic, the possibilities of technology hinted at a new world in which information could be shared among likeminded people, leaping over barriers of geography, race or class.

One of them was Steve Jobs, who was brought up in Palo Alto and who, in 2005, told a group of graduating students at Stanford in a famous speech: “The Whole Earth Catalog … was one of the bibles of my generation … it was a sort of like Google in paperback form, 35 years before Google came along. It was idealistic, and overflowing with neat tools and great notions.”

Jobs concluded his address with: “Stay hungry, stay foolish” – Brand’s motto from a mid-70s issue, intended as the final one, which Jobs claimed as his ethos and which has now become ubiquitous as a T-shirt slogan and meme. So what did the phrase mean to Jobs? “By the time he was espousing it, he was quite wealthy and powerful and I think aware of the innovator’s dilemma where you can put yourself out of business by not continuing to undermine your own work,” says Brand. “And ‘stay hungry, stay foolish’ was possibly a formula for him to keep coming up with the next thing. Even when the last thing was successful, he thought he was going to be destroyed by it.”

The documentary Alex Gibney made about Steve Jobs posited that, while Jobs was heavily influenced by the counterculture, he had ultimately used it to create machines humanity now can’t live without, rather than to enlighten society or himself. Brand, who got to know Jobs after the Stanford speech, disagrees.

“I think Steve was pretty enlightened by the end. Like everyone, once he got married, everybody said the cruelty went out of him and the kids humanised him enormously, so the ferocity became less sincere. But in terms of what he did and how he did it, I wouldn’t fault him. That he could do it that well – and to help inspire the Jeff Bezoses [CEO of Amazon] and the Elon Musks [CEO of Tesla] and characters who, to this day, continue to solve innovative dreams in this harsh reality, making stuff that fucking well works – is maybe a part of what he got from the Whole Earth Catalog.”

Our final stop is at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, the heart of Silicon Valley, where a century’s worth of mind-expanding technological progress is laid out. Our guide, curator Chris Garcia, is sceptical about whether Jobs can be regarded as a countercultural figure. “He wanted to change the world but he wanted to make himself a whole lot of money at the same time,” he says. “You know the phrase: ‘When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro’? He was definitely a pro from early on.”

Instead, Garcia points to another figure as one of the counterculture’s true heroes, his relative Jerry Garcia, leader of the Grateful Dead, still America’s biggest cult band when they staged their farewell concerts last year (Jerry died in 1995). He points to the fact that the Grateful Dead were so community-minded that they even had an enclave at their concerts where audience members could stand and tape the shows. “They were experimental, avant garde and they literally allowed people to record their concerts,” says Garcia. “That’s ridiculous, at a time when you were making money selling records, to let people make their own. So they were giving and they were experimenting and they were assisting, because anyone who could get a hold of Jerry would probably end up jamming back at their place for five or six days.”

Communal, giving and peaceable, it’s an ethos that still resonates, particularly in an ever more atomised, bad-tempered world. While the tens of thousands that headed out to the communes eventually came home, the sharing and free love proving more fraught than they had imagined, the ideals still have a powerful allure, as strange yet somehow comforting as the chorus of Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds. Although San Francisco is now one of the most expensive places on Earth, it’s still the home of dreams and big ideas, a reminder that other worlds are possible.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion