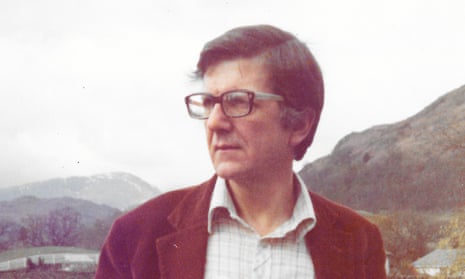

The poet and critic Bernard Bergonzi, who has died aged 87, was long associated with the teaching of 20th-century English literature at Warwick University. His books shed new light on the English writing of the first world war and the 1930s, and on developments in criticism since the 60s, which he largely disliked. Monographs on HG Wells, TS Eliot, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Thomas Arnold and Graham Greene showed Bergonzi at his sensible and lucid best.

Though principally known as a critic, it was as a poet that Bergonzi began to find a place in the English literary scene in the early 50s. Within a year of beginning research on the early writings of Wells in 1958, he was appointed assistant lecturer at Manchester University. A full lectureship soon followed. He published two books while at Manchester: The Early HG Wells (1961) and a study of the literature of the first world war, Heroes’ Twilight (1965), in which he gave innovative attention to David Jones and the nearly forgotten Henry Williamson. In the following year he was appointed senior lecturer at Warwick, where he remained until he formally retired in 1992. He became professor of English in 1971 and served as pro-vice-chancellor from 1979 until 1982. His career was closely tied to the ascending fortunes of the Warwick English department.

For a time Bergonzi sought to be something of an arbiter of contemporary writing. A series of talks, Novelists of the Sixties, was broadcast on the Third Programme and he became a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books. He edited Innovations (1968), an influential collection of essays on the avant garde, which may have given the impression that he was devoted to experimental writing. He was not. In The Situation of the Novel (1970), he expressed much liberal bafflement at the “facile apocalypticism” of 60s fiction.

Writers such as Thomas Pynchon began to make their presence felt in Bergonzi’s writing. But his book hardly celebrated new cultural energies. Nor was he particularly interested in American literature or French critical theories. In truth he posed “the ideology of being English” as a direct challenge to the cult of experimentalism. The English, he wrote, are an untheoretical people, who cherish their idiosyncrasies and amateurishness, and have a distaste for the systematic and the doctrinaire. Bergonzi hoped that “happy enclave of tradition and liberalism” might long endure.

He wrote with gusto against the perversity of Marxist, structuralist and psychoanalytic criticism. Feminist criticism seemed to him little more than special pleading. In The Myth of Modernism (1986) and Exploding English (1990) he argued that the gang of theorisers led by Terry Eagleton would find a happier home outside traditional English departments. The emergence of theory in literary education was itself a “symptom of disorder”. He deplored the fact that literary judgment no longer seemed to have a place in the global anglophone academy. Remaining true to the idea of evaluative criticism, he proposed an English degree course that would concentrate on the study of poetry, without its “culturalist” baggage. In all this, Bergonzi thought of himself as a defender of humane values against leftwing onslaughts.

His biographical and critical study TS Eliot appeared in 1972, avoiding the awkward personal questions about Eliot’s marriage and his politics that increasingly preoccupied critics in the decades after Eliot’s death in 1965. When the lawyer and academic Anthony Julius raised important questions of antisemitism in Eliot’s work in TS Eliot, Antisemitism and Literary Form (1996), Bergonzi was fair-minded in responding to a topic that he had largely ignored in his own study.

He attempted a wider survey of the major figures of the 30s in Reading the Thirties (1978). To his credit, when discussing the rightwing writers of that decade Bergonzi did not duck the question of Wyndham Lewis’s admiration for fascism, or Roy Campbell’s authoritarianism and Catholic triumphalism. But the politics of that supremely political generation is downplayed. Bergonzi published a critical b iography of Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1977, and in 1981 The Roman Persuasion, a novel set in 1936-38, about a pious Catholic literary family negotiating the perilous political crises of that decade. It offers a counter-history to the mythologies of the antifascist left in the 30s. As a novel, the family councils of the Cartwrights and Tolleybeares perhaps go on a bit too long about the church’s “infallible wisdom”.

In 1982 an essay by Bergonzi was included in Why I Am Still a Catholic, a collection edited by Robert Nowell. Bergonzi remained a lifelong practising Catholic, though of a distinctly liberal temperament. Occasionally describing himself as a “papist critic,” he was a man of the second Vatican council, and the winds of change that were blowing through the church in the 60s.

Bernard was born in Lewisham, south-east London, the son of Carlo Bergonzi, a dance band musician in the 20s and later a white-collar worker in factories, and his wife Louisa (nee Lloyd). Ill-health, which resulted in an operation on his ear in 1937, dogged his childhood but spared him what he later came to regard as “ignorant and unenlightened” Catholic schooling.

Strong on the need for authority and discipline and deeply suspicious of private judgment, Catholicism in the 40s was a difficult natural home for an inquiring spirit such as Bergonzi. He caused some consternation when he asked his parish priest if he might see a copy of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the list of books and authors proscribed by the church to which Jean-Paul Sartre was added in 1948 and André Gide in 1952. (The Index was discontinued in 1966.) Bergonzi found few English writers on it, but was quietly shocked at how questions about the Index, and whether it actually applied to his own reading, were dismissed as being of little consequence.

After leaving school before his 16th birthday, he worked as a junior clerk in the City, and continued to read widely if unsystematically in Catholic books and periodicals. The wartime Faber edition of Eliot’s collected poems, bought in 1946, had pride of place in his small library. He read successive issues of Penguin New Writing, greatly admiring an essay by John Wain on William Empson in the last number in 1950. Bergonzi thought of himself as an autodidact, not unlike the unfortunate Leonard Bast in EM Forster’s Howards End.

In his 20s he began to write poetry, strongly influenced by Eliot. Two of his poems were featured in Wain’s radio series First Reading on the Third Programme in 1953. Later that year he participated in a reading to launch Springtime, an anthology of poetry edited by GS Fraser and Iain Fletcher. Kingsley Amis, who was also a contributor, wrote to Philip Larkin the day after the reading that “a chap named Bernard Benghazi or some such name was good, I thought”.

Bergonzi contributed to George Hartley’s literary magazine Listen in 1954 and became co-editor of the later numbers of Oscar Mellor’s Fantasy Poets series. Godolphin & Other Poems appeared in 1952. A more substantial collection, Descartes and the Animals, followed in 1954. Three small-press pamphlets of poems, containing careful, disciplined and thoughtful work, were subsequently published.

At the suggestion of Fraser, in the autumn of 1953 Bergonzi enrolled at Newbattle Abbey, an adult residential college near Edinburgh. In 1955 he won a mature entrant scholarship at Wadham College, Oxford, where his tutor was FW Bateson. Bergonzi was an active member of the Critical Society, founded by Al Alvarez in the early 50s, and became friends with Martin Dodsworth and Christopher Ricks. He thought of himself as an ambitious, upwardly mobile scholarship boy.

The energy he displayed as a writer continued well after he became professor emeritus. His broad range of interests, and approach to the business of introducing literature to the general public, changed little over the decades. Wartime and Aftermath (1993), a study of English literature and its background in the 40s and 50s, drew heavily on his earlier publications and established judgments. War Poets and Other Subjects appeared in 1999. A Victorian Wanderer (2003), a biography of Thomas Arnold, brother of the Victorian poet, was warmly received. It was followed by A Study in Greene (2006).

Deploring those academics who chose to write for each other in jargon-laden prose, Bergonzi particularly objected to the way theorists seemed to ignore general readers. He was undogmatically certain that he had always written with those readers in mind, however much England and Englishness had changed since he began his career as a writer and teacher.

He is survived by his second wife, Anne Samson, whom he married in 1987, and three children, Ben, Clarissa and Lucy, by his first wife, Gabriel Wall, who died in 1984.

Eric Homberger

David Lodge writes: Bernard Bergonzi was one of my oldest friends. We met for the first time at a conference in Cambridge in 1961, when Bernard told me he had recently read my first novel, The Picturegoers (1960), and recognised its setting as the rather shabby part of south-east London, incorporating Lewisham, New Cross and Brockley, where like me he had grown up. He was six years older, but we had other things in common: both Catholics, both only children (an unusual combination) of lower-middle-class parents, both in the early stages of academic careers, specialising in modern literature, trying to add to it in poetry and fiction respectively, and earning extra income from reviewing.

When Bernard moved with his family from Manchester to the new Warwick University, less than an hour from Birmingham, where I was a lecturer, the friendship developed to include regular Sunday lunches at both venues. After the devastating death of his first wife, Gabriel, from cancer at the age of 46, this custom was revived during his second marriage, to Anne. I always looked forward to these meetings because we had plenty to talk about: new books, our current projects, literary and academic gossip, and the state of the Catholic church. Bernard took a particular interest in my novels that dealt with this last subject, and wrote perceptively but not uncritically about them.

In his prime he was an imposing figure, confident, witty and urbane, a man of letters in a traditional mould, and this was a personal triumph over a disadvantaged childhood, including two years in hospital that seriously retarded his education. The long row of his books on my shelves display an impressively wide knowledge of modern literature and culture, communicated in effortlessly readable prose at a time when academic criticism became increasingly heavy with jargon. Bernard deplored the impact on his profession of structuralism and poststructuralism, in which I found some ideas of value, but unlike many hostile commentators he read the work of their proponents carefully and described it fairly. He was a gentleman of letters.

Bernard Bergonzi, poet, critic and academic, born 13 April 1929; died 20 September 2016

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion