‘The idea of making ourselves into a vocal orchestra came to us when songs were difficult to remember, and we longed to hear again some of the wonderful melodies and harmonies that uplifted our souls in days gone by.’

So explained multi-talented missionary Margaret Dryburgh as she stood before her fellow prisoners and introduced the very first performance of the women’s vocal orchestra in a prisoner-of-war camp in Sumatra. The idea of a vocal orchestra was conceived by her fellow internee and Royal Academy of Music graduate, Norah Chambers. The date was 27 December 1943, some twenty months since they had first been imprisoned by the Japanese. By this point in their internment the women were experiencing terrible cuts in their already woeful food rations, malaria and dysentery were rife across the camp, and energy levels and morale were very low. It was Norah’s hope that this new vocal orchestra would transport both its audience and its singers beyond the confines of the camp and help to give them some of the strength they would need to survive the nightmare of captivity. Singing to survive.

This was by no means the women’s first foray into entertainment. In their previous camp – a compound of houses and garages in Palembang – there had been sing-songs, glee nights, country dance classes, even a fashion show. Sunday services, led by Miss Dryburgh (she was rarely if ever referred to by her first name in the camps as a mark of respect), in Garage 9 had become a weekly highlight for many. On 5 July 1942 attendance was rewarded with the very first performance of The Captives’ Hymn, a beautiful, uplifting masterpiece that she had composed herself and first sang with Shelagh Brown and Dorothy MacLeod to the gathered internees.

Throughout her captivity Miss Dryburgh was a vital source of spiritual and musical sustenance to her fellow prisoners and was cited by survivors of the camps as a beacon of hope during their long ordeal. Soon after the debut of The Captives’ Hymn, Miss Dryburgh joined forces with Norah Chambers to further contribute to the camp’s various music groups and events, with the former arranging the harmonies and the latter writing out the manuscripts. As Norah Chambers later remembered of her musical collaborator: ‘You could go to her, hum a tune and straight away she could write it down and harmonise it,’ while Chambers’s own skill was in copying the sheet music at great speed.

The pair became a close and highly-productive team as Chambers recalled:

‘We got on so well together… when I look back over all our music, I cannot imagine how we did it all in two short years.’

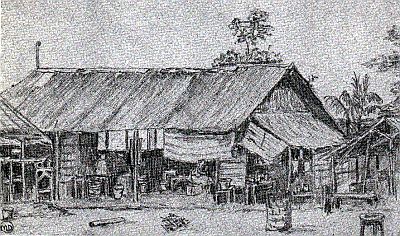

In the early months of 1943, after the women sought to celebrate their first Christmas in camp, with the choral society providing as much festive cheer as they could muster, the stresses and strains of camp life started to tell. Increasing ill health and further cuts to rations (which Margery Jennings described in her diary as ‘not enough to feed a mouse’) had a serious affect on the women’s morale, but worse was yet to come. In September, the women were moved to a barracks camp that had previously held their male counterparts and was therefore referred to as ‘the Men’s Camp’. Some 600 women and children were held in this new camp. British, Dutch, Australian and 21 other nationalities were all crammed into a deeply insanitary compound with over 50 to a hut and 27 inches of bed space each.

Molly Smith (formerly Ismail) later recalled:

‘I felt utterly desolate. At least in the bungalows [of the previous camp] there was some semblance of a home and a community. This seemed totally a prison and somehow final, as if this is what had been waiting us all along.’

Despite their reduced circumstances, which also included the total absence of instruments – they had no choice but to leave behind three pianos in the previous camp – Norah Chambers remained undeterred. In October 1943, while Margaret Dryburgh was out of action with Dengue Fever and morale was faltering, Norah hit upon the idea of starting a vocal orchestra, using voices in place of instruments. She felt it would be a way to bring various nationalities together as words were not needed, and help take their minds off their hunger and distress. Chambers, a violinist, who had a great love of orchestral music and had received excellent training in the Royal Academy Orchestra for three years under Sir Henry Wood, thought:

‘Why not use some of the marvellous orchestral or piano music which we all remember and love. We could arrange these as a ‘string quartet’ using 1st and 2nd sopranos and 1st and 2nd altos to ‘sing’ the notes of the conventional 1st and 2nd violins, viola and cello.’

Margaret Dryburgh’s initial reaction to Norah’s scheme was: ‘Ooh! I’m not sure if that will work, but let’s give it a try’ and together they set to work. They condensed complex works, taking main themes with the right modulations and harmonic changes, then weaving them into miniature works – complete in themselves. It was total collaboration. Norah chose the works they could try and Margaret worked most of them out with Norah doing those she did not know (such as Ravel’s Bolero) or when she ran into difficulties.

Norah later recounted how they started with a ‘simple piece,’ Tchaikovsky’s Andante Cantabile for Strings, ‘which was only four voices… we hummed to get sounds and used consonants to get rhythms, and light and colour from the voices.’ Norah then started training the groups as only about six out of the thirty could read music. The singers were divided into 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th parts. She took each group separately at first then together in rehearsals. While the parts practised individually around the camp out of earshot of the guards, the rehearsals, which Norah conducted usually twice a week, took place in the Dutch kitchen at dusk or at night. Margaret sang with 2nd altos (fourths) and with perfect pitch, always gave the starting notes. Norah remembered:

‘We clean forgot where we were during those rehearsals and you see that was so important.’

A concert was planned for 27th December 1943 to mark their second Christmas in captivity. Among the singers in the vocal orchestra were Norah’s best friend in the camps, Audrey Owen; Norah’s sister, Ena Murray; Shelagh Brown and Dorothy MacLeod who had been part of the trio to first sing Margaret Dryburgh’s The Captives’ Hymn; British nurse Olga Neubronner; Dutch sisters Antoinette and Alette Colijn; Dutch nun, Sister Catharinia; three Australian nurses, ‘Mickey’ Syer, ‘Flo’ Trotter and Betty Jeffrey; and Sigrid Stronck, a Dutch mother of two. In this way the orchestra united different nationalities in the camp as the music they learned together helped to break down barriers.

Four of the Vocal Orchestra members: Sister Catharinia, Flo Trotter, Betty Jeffrey and Sigrid Stronck

The ‘Christmas Concert’ as it would later be coined, was keenly anticipated by the internees, as Helen, the eldest of the three Colijn sisters, recalled: ‘The camp still didn’t know what the programme would be. The new choir had been practising in the greatest secrecy. But those of us not involved with the programme sensed that it was going to be something special. In my barrack, several women were ‘dressing up’ for the event.’ Not everyone in the camp was enthusiastic, either because they believed that the choral activity was a waste of precious energy or because they were fearful of Japanese reprisals for the organisation of a mass social gathering, as these were not permitted. Helen’s account continues:

‘Someone had scratched letters on one side of the dirt floor… O.R.C.H.E.S.T.R.A, I read. Was someone trying to be funny? There wasn’t a single musical instrument in this camp… At 4:30 sharp, 30 women filed behind Norah Chambers from the central kitchen towards the pendopo [a sheltered area in the centre of the compound]. Each carried pieces of paper in one hand and a little stool in the other [the women being too weak to stand throughout the performance]. I saw no instruments.’

Prisoners gather in the centre of the compound to listen to the first Vocal Orchestra concert in the film ‘Paradise Road’ (© Fox Searchlight Pictures)

Margaret Dryburgh introduced the concert, explaining how the vocal orchestra had come about and how it would seek to reproduce music performed by a traditional orchestra. After detailing the pieces in the programme, which included Dvorak’s Largo from the New World Symphony, Chopin’s Raindrop Prelude, and Debussy’s Reverie, she explained:

‘We do not profess to reproduce the effects or quality of stringed or reed instruments, but as the lovely melodies and harmonies of the Great Masters greet your ears you may imagine you hear them’.

She also requested that the audience closed their eyes and imagined themselves in a better place. Largo was the first piece and immediately entranced those gathered. Helen Colijn recalled:

‘The music soared into its first rich and full crescendo. I felt a shiver go down my back. I thought I had never heard anything so beautiful before.’

Despite the threat briefly posed by the arrival of several guards, who rather than calling a halt to proceedings, elected to stay and listen instead, the programme went without a hitch and concluded with Auld Lang Syne, which proved an even more appropriate ending when, due to popular demand, the entire concert was repeated in its entirety a few days later on New Year’s Day.

Orchestra member Flo Trotter later recounted:

‘That concert did wonders for the camp. The women said it helped to renew their sense of human dignity and feeling of being stronger than the enemy. That night, everyone forgot about the rats and the filth.’

For a time the vocal orchestra continued alongside the glee and variety nights, and the choral group, although some women who were singing with several groups suggested saving their energies for the vocal orchestra. Of the latter, Betty Jeffrey wrote in her diary: ‘It is absolutely marvellous, the most fascinating thing I have ever done. A wonderful experience, and out of this world singing this music.’

However, after the third concert on 17 June 1944, recorded in Margery Jennings’ diary as ‘not as good as before’, presumably due to further weakened state of its members, the orchestra did not perform again.

As the women and children entered their final year of captivity and endured two dreadful journeys to new and even more insanitary camps, at Muntok on Bangka Island and later back on Sumatra in Belalau,near Loebuk Linngau, many of them finally succumbed to malnutrition and disease. Norah Chambers later reflected: ‘Our vocal orchestra was silenced forever when more than half had died and the others were too weak to continue…..it was wonderful while it lasted.’

Margaret Dryburgh, who had played such an important role in so many camp activities, not the least of which was her wonderful contribution to the musical life of the camps, died in April 1945, shortly after their arrival at their final camp. Norah Chambers however was to survive the war, along with several members of the vocal orchestra, and would not only live to see the music she had worked on in the camps with Margaret published, but in the Eighties also performed in the United States and the Netherlands. Later the music would also be performed across Australia.

In 1986, original orchestra member Shelagh Lea (formerly Brown), on hearing a cassette of a Dutch vocal orchestra conducted by Dirk Jan Warnaar, commented:

‘My wish at the first camp concert was that… If only we could be heard at home… at least the notes could get up and out of that dreary place. Now after all these years, here they came back to us. Thank you ….amazing.’

In October 2013, as the 70th anniversary of that first concert approaches, British voices will give a performance of the vocal orchestra material, as well as recounting the incredible story of the two inspiring British women, Margaret Dryburgh and Norah Chambers, who collaborated to bring hope and the will to survive through music. They may no longer be with us (Norah Chambers died in June 1989) but their inspirational work lives on today, an anthem for triumph over adversity.

References and acknowledgements: This history of the Vocal Orchestra, written by Andy Priestner, contains excerpts from the following books: ‘Women Beyond the Wire’ by Lavinia Warner and John Sandilands; ‘White Coolies’ by Betty Jeffrey, and ‘Song of Survival: Women Interned’ by Helen Colijn. It also benefited from information, suggestions, and corrections gratefully received from Diane Whitehead, Cara Kelson, and Shelagh Lea’s daughter, Margaret Caldicott.