This story was supported by the journalism non-profit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

When I plunged from the middle class into poverty in 2013, a lot of things I took for granted went down the chute, including my six-figure salary, my comfortable lifestyle, and my self-esteem. But my finances, under long-term repair after a bitter divorce, crashed and burned.

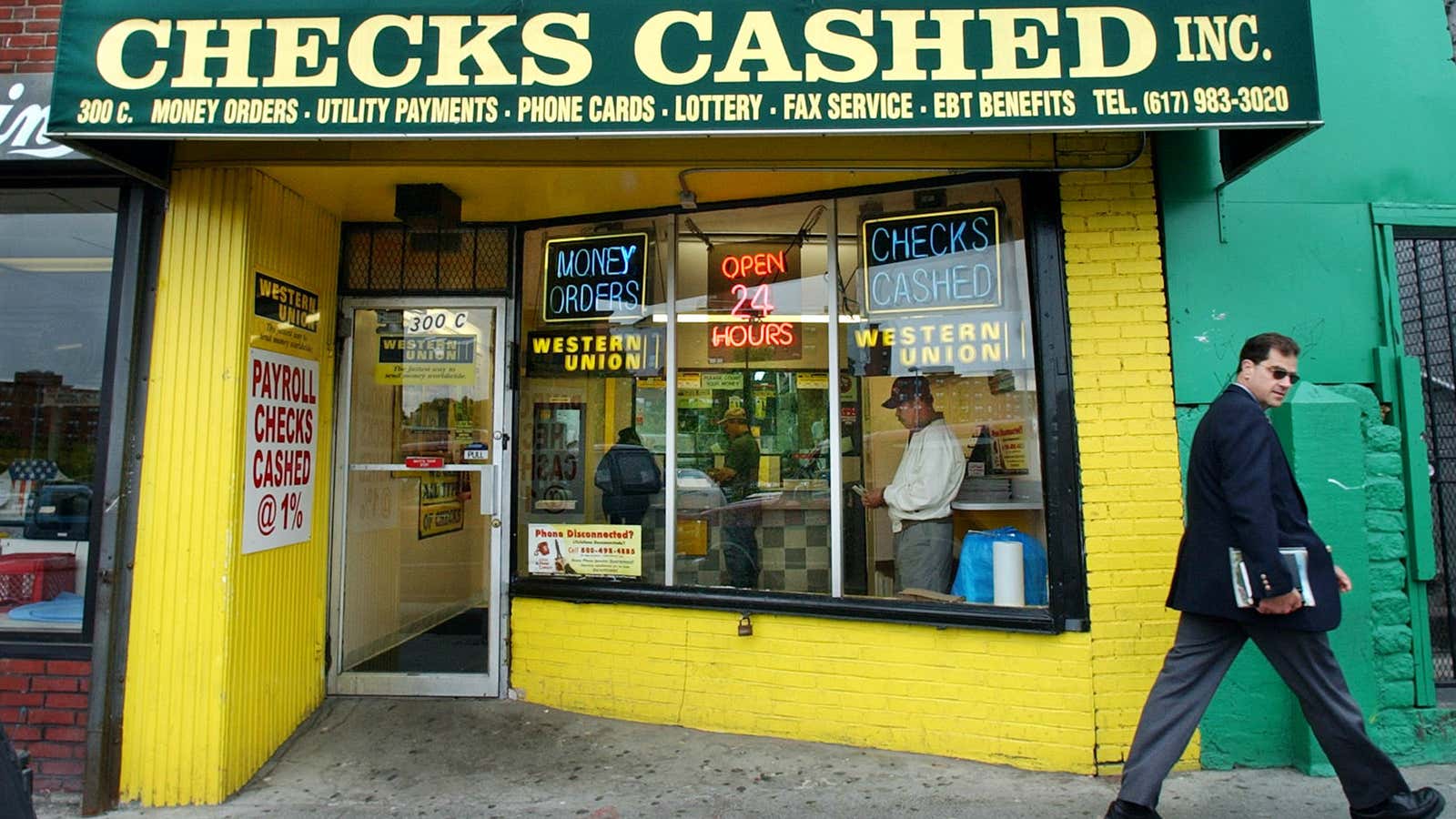

Overnight, I became reliant on so-called “alternative” banking services—check-cashing stores, payday loans, and prepaid credit cards—that I barely knew existed beforehand. I did so to get by in my miserable new life.

Out of necessity and desperation, I was suddenly beholden to an industry that has triple-digit interest rates, hidden user fees, and financial trap doors built into nearly every transaction. I found myself routinely dealing with people, going to places, and doing questionable things that I, and many of the inhabitants of my old middle-class life, could barely imagine.

Working-class African Americans and Hispanics with no college education remain the demographics most likely to use check-cashing and payday-loan stores; I’m black and I have a college degree. But banking-industry experts and economists say a new profile has emerged: college-educated borrowers, like me.

People who, we assume, should know better.

The transactions happen at places like the Ace Check Cashing store, a no-frills, fluorescent-lit parody of a bank, dead in the heart of the H Street Northeast corridor, a gentrifying neighborhood in Northeast Washington. Next door to a grubby city social-services office—an unhappy place with a perpetual clutch of black and brown seniors, and twenty-something couples and their children, looking for government help—Ace Check Cashing was a financial outpost for the black and poor, and my high-priced financial oasis in desperate times.

Yet outfits like it—along with pay-as-you-go credit cards, payday loans with interest rates of 400%, and the other “alternative-banking” services like the ones I used to keep me afloat—are creeping up the class ladder from the working poor to what’s left of the middle class. A growing number of consumers with homes, decent jobs, families, and mainstream bank accounts are showing up at places like Ace, or going online, to take out pricey payday loans, desperately trying to maintain their place in the middle.

Lisa Servon, a University of Pennsylvania professor who spent four months working in a check-cashing store as part of her research of unbanked households says there’s no doubt that more middle class people are using them as banks of last resort.

“A lot of the people I talked to had public-sector jobs, jobs with decent salaries,” says Servon, author of The Unbanking of America: How the New Middle Class Survives, her first-person account of the alternative-banking industry. “But for a lot of reasons they weren’t able to save [for an emergency] or make ends meet.”

A recent study from the Chicago Federal Reserve put a finer point on it.

“As might be expected, payday borrowing is lowest among those with a college degree,” according to the study, produced in 2015. “However, when examining changes from 2007 through 2013, payday borrowing rates for those with some college roughly doubled from 3.8% in 2007 to 7.7% in 2013.

“In contrast, for those without a high school diploma,” the study says, “payday borrowing was only a bit higher in 2013, at 3.0%, than it was in 2007 at 2.9%.”

Not surprising, says Servon.

“What happens is that people suffer some kind of a shock that they’re not prepared for,” Servon says, like a young adult child that’s lost her hourly-wage job and can’t pay her rent, or a drug-addicted relative who needs to go to rehab.

The frayed social safety net, an economy in transition, a middle class hollowed out by the Great Recession, and other factors have made a sizable chunk of Americans—already working harder than their parents did, just to stay in place—less able to have a rainy-day fund of a few thousand dollars in the bank.

That means they’re not only more susceptible to suffer an economic free-fall than they were just a few years ago, they’ll probably crash hard, broke, and desperate, if they do.

Enter the payday lenders and check cashers, purveyors of just-in-time funds with relatively low payments—dirty credit (or no credit) acceptable! Just fill out a few forms, or make some clicks online, and anywhere from $300 to $5,000 can appear in just minutes.

But the downside to getting money from Hail-Mary sources can be substantial, including fees and interest-rate percentages that might make Tony Soprano jealous. In the case of payday loans, that means minimum monthly payments that are enticing but that barely make a dent in the principal, and revolving credit designed to keep the borrower on the hook for as long as possible, paying as much as $1,000 in interest on a $300 loan.

“Payday loans are sold as two-week credit products that provide fast cash, but borrowers actually are indebted for an average of five months per year,” according to a 2012 study by the nonprofit Pew Charitable Trust. Moreover, “despite its promise of ‘short-term’ credit, the conventional payday loan business model requires heavy usage to be profitable—often, renewals by borrowers who are unable to repay upon their next payday.”

Servon saw the evidence first-hand.

“I did interviews with payday borrowers. One woman had worked for a paralegal—she was put on furlough,” Servon says. “It was totally unexpected, nothing that was her fault.”

Her cash, however, ran out before another job came through.

“She took out payday loans,” Servon says, “and she’s still paying them back.”

* * *

My odyssey from the middle class to Ace Check Cashing, speaking with a teller through a window of three-inch-thick bulletproof-glass, was simultaneously surreal and jarring.

On paper, I’d done everything right: bachelor’s degree, on full scholarship, from a good school, career job straight out of college, steady climb up the journalism ladder, one rung at a time, moving from one major media outlet to another and gaining responsibility and visibility as I went. Not long after arriving in Washington in 2005, I became a cable-news talking head, analyzing politics for Politico. I was middle-aged but still on the rise, ugly divorce notwithstanding. Bright future, shades on.

It came to a crashing halt in 2012, after I lost my lost my high-profile job. In the frenzy of Washington political gossip that followed, personal details from my ugly divorce surfaced. Then, on live TV, I said that Mitt Romney, then a 2012 Republican presidential candidate, was uncomfortable around minorities. Angry conservatives combed my social media accounts and found a tasteless joke I’d repeated about Romney. The career killshot: I’d been charged with assault after an intense argument with my ex-wife a few months earlier. When I got fired, my court file was leaked to a DC gossip columnist. I plummeted from rising star to fallen hero, demolishing my finances on the way down.

Six months later, unemployed and essentially blackballed from journalism, I fell behind on rent and was evicted from my $2,000-a-month, two-bedroom apartment in suburban Maryland, destroying my already fragile credit score. My mainstream megabank kicked me out after I blew through meager savings and racked up $1,600 in overdraft fees. My credit card melted after just a few weeks’ use.

I ultimately crash-landed in Northeast Washington, living out of a suitcase in the cramped basement guest room—full-sized bed, ground-level window, lamp, nightstand—of an incredibly generous family I barely knew who owned a renovated, four-bedroom townhome just off H Street NE. I’d skidded to a halt in the ranks of the newly poor.

That fall through the looking glass involved applying for food stamps at the social services office, navigating the hardscrabble section of their neighborhood, and mowing a friend’s lawn for $50 a cut (pocket money for hanging out with my kids). Among the things I found disturbing, though, was my time as Alice-in-Payday-Lending Land, new patron of a complex world of financial services for the poor.

Going to the Ace Check Cashing store and taking my place in line behind an elderly black man in shabby clothes, leaning on a cane, and a tired-looking young Hispanic woman wearing a T-shirt plastered with the name of a cleaning company, was a decision that was easy and difficult at the same time.

Both my parents are Great Depression babies who grew up poor under Jim Crow in rural Maryland but worked and sacrificed to carve out a middle-class lifestyle for me and my sisters. Preaching thrift and financial responsibility, their sermons clung to me, but didn’t always stick. When I fell on hard times, the lessons went completely out the window.

Walking into Ace, at the corner of 6th and H streets in DC’s Atlas neighborhood, felt like strolling into a strip club on Sunday morning: Embarrassing and shameful, a betrayal to my parents’ values. “Places like this,” I thought, “are for other people—that hard-hat worker with muddy boots and a cigarette behind his ear, filling out a loan application at the counter. That tattooed mom in the nurse’s scrubs behind me, wrestling with her hyperactive four-year-old son. My crackhead cousin, somewhere in the Baltimore projects. My kinfolk in the Maryland countryside, getting by on government disability.”

The people I believed I was better than.

My brain, my empty wallet, my growling stomach, and the $50 check in my pocket argued different: ”You need food, and you have the kids next weekend. The bus ain’t free and you can’t eat pride. Go in, and cash the damn check.”

In the queue at Ace that summer evening in 2014, exhausted, sweaty, waiting to fork over a Happy Meal’s-worth of the money I just earned—taking my place behind a middle-aged woman in denim shorts, T-shirt and cheap sneakers, and pink foam rollers peeking out from under her scarf—a James Baldwin quote lit up in the back of my stressed-out brain. I couldn’t remember where I’d heard it; maybe in college or a PBS documentary, but in that moment the context was as bright as the buzzing neon sign out front.

“Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty,” Baldwin once wrote, “knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.”

* * *

I might have been a stranger to the world of the underbanked, but research shows I wasn’t alone. The same economic hurricanes that have eroded the middle class—declining wages, rising costs of living, employers squeezing the work of two employees out of just one, the ruinous housing bust—gave me plenty of metaphorical company.

“Twelve million American adults use payday loans annually,” according to the Pew survey. Researchers found “about 5.5% of adults nationwide have used a payday loan in the past five years, with three-quarters of borrowers using storefront lenders and almost one-quarter borrowing online.”

At the same time, “while lower income is associated with a higher likelihood of payday loan usage, other factors can be more predictive of payday borrowing than income,” the survey found. “For example, low-income homeowners are less prone to usage than higher-income renters: 8% of renters earning $40,000 to $100,000 have used payday loans, compared with 6% of homeowners earning $15,000 up to $40,000.”

Servon says middle-income earners who survived the Great Recession, only to see their homes foreclosed upon, their jobs outsourced, and entire industries collapsing, are facing stiffer economic headwinds than their parents or grandparents.

“Then there’s income volatility, especially with the gig economy,” she says; think Uber driver, an independent-contractor, no-benefits job where the size of a paycheck is determined by the number of hours spent behind the wheel, or workers holding down two or three jobs to take care of themselves or their families. “People are less able to predict their income from month to month. Their income profile is marked by spikes and dips.”

Throw in the retraction of public and private safety nets—shrinking government unemployment and food benefits, higher health-insurance premiums, child care that can cost as much as a college tuition—and it’s clear why the middle class savings rate is collapsing as alternative banking booms, raking in roughly $7.4 billion in annual profits.

Take unemployment insurance, a Great Society godsend that can hold households together short-term. The payouts, however, vary from state to state, are only available for 26 weeks, and can be as low as $200 a week—hardly enough to cover groceries and gas, let alone rent or doctor’s bills, for a family of three in most places.

Even relatively generous unemployment benefits in Washington don’t go very far in the nation’s third-costliest city, where a studio apartment in a decent neighborhood can set you back $1,600 a month, you’ll spend around $130 a month in utilities for that apartment, and round-trip subway fare to work (or a job interview) runs about $6, conservatively, each day—or, $140 a month.

The financial shock of a laid-off worker plummeting into the social safety net “used to be absorbed by the public and private sector,” Servon says: Healthy severance packages, including job-placement help, along with public assistance used to be the norm. Now, as cash aid becomes stingier, families are harder-pressed to scrape together $2,000, in savings or on a credit card, for red-light emergencies—a major car breakdown, a sudden medical catastrophe, an unexpected death in the family.

“Now,” she says, “a lot of that [shock absorption] is forced on the individual.” Under those circumstances, payday lending and check cashing can make sense. The urgent, short term need—money right now—outweighs the greater, long-term costs. And the new profile of the alternative-banking customer tells the economic tale.

“When we looked at people’s situations, we looked at their households,” says Servon, describing her analysis of the average customer at the store in which she worked. “I encountered a lot of people who were helping their older children” who’d moved back home because of a financial disaster.

At the same time, many borrowers are succumbing to pressure of maintaining the middle-class lifestyle they knew, including paying for homes with underwater mortgages or writing checks for their child’s college tuition in an era of stingier state and federal student financial aid. A decade ago, Servon says, a middle-class income might have covered those expenses, with some left over for the piggy bank.

“They feel like there’s something they should be doing but they can’t do,” Servon says.

“The landscape has changed.”

* * *

When it was my turn to see the cashier at Ace, there wasn’t a lot of chit-chat like with the tellers at my old megabank. She handed me a form—name, address, phone, and social security numbers—then had me stand in front of a camera fastened on top of a computer terminal, taking a photo to enter into the system along with my information.

“Fraud protection,” she said.

Five minutes later, I had my cash. The price was $8 and a chunk of my self-respect.

Yet there are signs that check-cashing stores and payday loans aren’t going away; in fact, the concept is entering the mainstream—a sign of the financial times.

Sensing an opportunity to get in on the alternative-banking cash machine, a growing number of megabanks are tacking on a $5 or $6 surcharge to cash a check for customers who don’t hold accounts, a new revenue stream. Walmart charges $3 for every check under $1,000, and $6 for larger amounts. Smaller banks are offering middle-interest, short-term micro-loans to help customers out until they get paid again.

And it makes sense: According to the Chicago Federal Reserve, America’s big banks processed 5.4 billion checks in 2015, with an average dollar amount of $1,487 per check. But as direct-deposit services, bank-sponsored smartphone apps, and no-envelope ATMs have exploded—along with person-to-person money-transfer apps like Venmo and PayPal—the cost to process a paper check has plunged along with its frequency, and going to the bank to do it has become almost obsolete.

Unless, of course, you’re among the working poor.

I made a handful more visits to Ace that summer, cashing birthday checks or quickie loans from my relatives, until I got a regular job in 2015 and used my credit union savings account to manage my earnings. Since then, I’ve moved into my own place and am on more solid financial ground.

While I’d like to claim I went back to Ace, closed my account, and put that unhappy storefront behind me for good, I can’t: My current, full-time journalism job, which I love, still pays me $45,000 less per year than I earned before my great fall, my wrecked credit is still in drydock, and my daughter is headed to college in August. I’ve got two part-time freelance jobs to bring in extra money, but I’m keeping Ace is in my back pocket. Because, you never know.

While my story has only a somewhat less-than-happy ending, a lot of people aren’t so lucky, locked into paying exorbitant fees to payday lenders and check cashers to keep things together. And, sadly, it’s likely to get worse.

President Donald Trump and his GOP allies on Capitol Hill are itching to roll back post-Great Recession banking regulations, gut rules governing payday lending, defang federal watchdogs like the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and relax Congressional oversight designed to prevent the sort of predatory banking I fell prey to as a member of the working poor.

Indeed, Trump has given the Republican-majority Congress a green light to swing the wrecking ball at president Barack Obama’s financial reforms. In May, as Wall Street egged them on, GOP senators held hearings on plans to rewrite the Dodd-Frank oversight laws, and urged Trump to fire Richard Cordray, the CFPB’s first and only director.

The safeguards protecting me and others in the same economic boat are getting weaker, and the economy shows no sign of a rising tide that would lift us back into the middle class.

Bottom line: While I’m better off now than I was three years ago, I’m still a long way from where I used to be. And this might be as good as it gets.