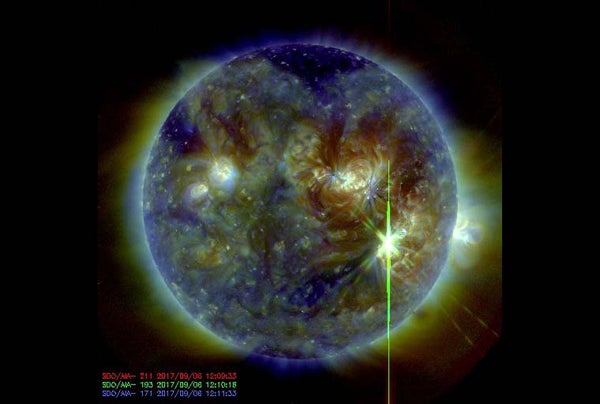

Early this morning (Sept. 6), the sun released two powerful solar flares—the second was the most powerful in more than a decade.

At 5:10 a.m. EDT (0910 GMT), an X-class solar flare—the most powerful sun-storm category—blasted from a large sunspot on the sun's surface. That flare was the strongest since 2015, at X2.2, but it was dwarfed just 3 hours later, at 8:02 a.m. EDT (1202 GMT), by an X9.3 flare, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Space Weather Prediction Center (SWPC). The last X9 flare occurred in 2006 (coming in at X9.0).

According to SWPC, the flares resulted in radio blackouts: high-frequency radio experienced a "wide area of blackouts, loss of contact for up to an hour over [the] sunlit side of Earth," and low frequency communication, used in navigation, was degraded for an hour. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Solar flares occur when the sun's magnetic field—which creates the dark sunspots on the star's surface—twists up and reconnects, blasting energy outward and superheating the solar surface. X-class solar flares can cause radiation storms in Earth's upper atmosphere and trigger radio blackouts, as happened earlier this morning.

During large solar flares, the sun can also sling a cloud of energetic plasma from its body, an event called a coronal mass ejection (CME).

"It was accompanied by radio emissions that suggest there's a potential for a CME," SWPC space scientist Rob Steenburgh told Space.com. "However, we have to wait until we get some coronagraph imagery that would capture that event for a definitive answer."

The sunspot responsible for this morning's flares, active region 2673, is the smaller of two massive spots on the sun's surface, at only seven Earths wide by nine Earths tall, according to astrophysicist Karl Battams.

Yesterday, that same sunspot emitted an M-class solar flare—one-tenth the size of an X-class flare—leading to a coronal mass ejection aimed toward Earth that could cause auroras tonight as far south as Ohio and Indiana.

The orbiting Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, a joint project between NASA and the European Space Agency, is currently out of contact with Earth because of its location, so observers will not be able to see any coronal mass ejections caused by this morning's flares until 10:30 p.m. EDT (1830 GMT), Battams wrote on Twitter.

If aimed toward Earth, such an ejection could lead to even more spectacular auroras, but could also damage satellites, communications and power systems. That cloud of charged plasma would arrive within 1 to 3 or 4 days, Steenburgh said, although CMEs triggered by energetic flares generally come quickly.

The surge of activity might seem surprising, as the sun is approaching its solar minimum, with the lowest levels of activity in its 11-year cycle.

"We are heading toward solar minimum, but the interesting thing about that is you can still have events, they're just not as frequent," Steenburgh said. "We're not having X-flares every day for a week, for instance—the activity is less frequent, but no less potentially strong."

"These kind of events are just part of living with a star," Steenburgh added.

EDITOR'S RECOMMENDATIONS

Space Weather: Sunspots, Solar Flares & Coronal Mass Ejections

Totally Active: Eclipse Photos Reveal Sunspots, Solar Flares

Copyright 2017 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.