John Cryan was originally trained as a neuroscientist to focus on everything from the neck upwards. But eight years ago, an investigation into irritable bowel syndrome drew his gaze towards the gut. Like people with depression, those with IBS often report having experienced early-life trauma, so in 2009, Cryan and his colleagues set about traumatising rat pups by separating them from their mothers. They found that the microbiome of these animals in adulthood had decreased diversity, he says.

The gut microbiome is a vast ecosystem of organisms such as bacteria, yeasts, fungi, viruses and protozoans that live in our digestive pipes, which collectively weigh up to 2kg (heavier than the average brain). It is increasingly treated by scientists as an organ in its own right. Each gut contains about 100tn bacteria, many of which are vital, breaking down food and toxins, making vitamins and training our immune systems.

Cryan’s study didn’t attract much attention, but a few years later, Japanese scientists bred germ-free animals that grew up to have an elevated stress response. This alerted Cryan and his colleagues that they might be able to target the microbiome to alleviate some of the symptoms of stress, he says.

The hope is that it may one day be possible to diagnose some brain diseases and mental health problems by analysing gut bacteria, and to treat them – or at least augment the effects of drug treatments – with specific bacteria. Cryan and his colleague Ted Dinan call these mood-altering germs “psychobiotics”, and have co-written a book with the American science writer Scott C Anderson called The Psychobiotic Revolution.

The psychobiotics of the title are probiotics that some scientists believe may have a positive effect on the mind. Probiotics are bacteria associated with healthy gut flora – such as the Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis we see advertised in “live” yoghurt. More diverse bacterial cocktails can also be bought as food supplements, but they’re expensive.

Cryan and his team went on to work with germ-free mice. “In these mice, the brains don’t develop properly,” he says. “Their nerve cells don’t talk to each other appropriately, thus implicating the microbiome in a variety of disorders ... We’ve also shown changes in anxiety behaviour, fear behaviour, learning, stress response, the blood-brain barrier. We found a deficit in social behaviour, so for social interactions we have an appropriate repertoire of bacteria in the gut as well.”

Over the past decade, research has suggested the gut microbiome might potentially be as complex and influential as our genes when it comes to our health and happiness. As well as being implicated in mental health issues, it’s also thought the gut microbiome may influence our athleticism, weight, immune function, inflammation, allergies, metabolism and appetite.

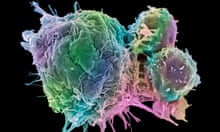

The past month alone has seen studies linking the gut microbiome with post-traumatic stress disorder (people with PTSD had lower than normal levels of three types of gut bacteria); fathoming its connection with autoimmune disease; finding that tea alters the gut microbiome in anti-obesogenic ways; showing that “ridiculously healthy” 90-year-olds have the gut microbiome of young adults; and how targeting mosquitos’ gut flora could help beat malaria by increasing the malaria-attacking bacteria in their guts. And last week, two groundbreaking studies provided evidence that gut biodiversity influences whether or not immunotherapy drugs shrink tumours in cancer patients.

One story that caught the public’s imagination during the summer implied that “poop doping” (AKA microbiome enhancement via faecal transplant; what has been delicately described as a “reverse enema”) could become the new blood doping for elite cyclists. Lauren Petersen, a research scientist at the Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine in Connecticut, looked at the stool samples of 35 cyclists, comparing those of elite and amateur cyclists. So sure was she that she would benefit from having some of the bacteria found in the gut microbiome of elite cyclists that she doped herself with the faeces one had donated. An endurance mountain biker herself, she swears (but can’t prove scientifically) that this took her from feeling too weak to train to winning pro cycling races. However, when you consider that one gram of faeces is home to more bacteria than there are humans on Earth – and how little we understand about the vast majority of them, good and bad – this is definitely not recommended.

An understanding of the gut’s importance to our wellbeing now fuels a global probiotic market projected to grow to $64bn (£48bn) by 2023. This month in Washington DC, the microbiome is a headlining topic at the world’s largest international neuroscience conference, for its potential role in helping to diagnose and slow the progress of degenerative brain diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

The challenge lies in pinpointing the cause and effect of specific bacteria, and translating the results into treatments. This isn’t easy. Giulia Enders, who wrote the international bestseller Gut, says: “We can check the stool for typical pathogens that would cause diarrhoea or viruses, but we have no idea what all the seemingly normal bugs are doing. We don’t really know which bacteria does what in who, so it is a big experiment.”

It’s a long, expensive process to test each strain in isolation, so scientists have started with small-scale human studies. Cryan tested Lactobacillus rhamnosus, which had reduced stress in his mice, on 29 people and found no benefit when compared with a placebo. But when he gave 22 healthy men a strain called Bifidobacterium longum 1714 for four weeks, the subjects presented lower levels of anxiety and stress hormone than before, and made between two and five fewer mistakes in memory tests. It looks as though B longum 1714 could be a bona fide psychobiotic, although Cryan says larger-scale human studies are needed.

Philip WJ Burnet, associate professor at the psychiatry department at the University of Oxford, has had promising results testing the effects of prebiotics on mood. Prebiotics are complex carbohydrates that humans can’t digest, but that probiotic bacteria thrive on. Essentially, prebiotics “are dietary fibres that feed bacteria already in our gut,” he says. “I argued that instead of proliferating the growth of single species as in taking a probiotic, if you eat these fibres you grow lots of species of good bacteria, so you’re more likely to get a hit.”

A very small, short trial – three weeks and involving 45 healthy volunteers – tested a commercially sold prebiotic called Bimuno, and suggested this might have the potential to reduce anxiety. “When you give someone an antidepressant,” says Burnet, “before you see a change in their depression or anxiety, it changes some underlying psychological mechanisms. You’re more vigilant to the positive, for example, if you’re on an antidepressant or are happy.”

In his study, people without the supplement or in the placebo group paid more attention to negative imagery because, he says, “I think we’re naturally morbid … But those on Bimuno paid more attention to the positive.” He is cautious to point out, however, that when people take antidepressants, these early changes don’t necessarily lead to their depression and anxiety symptoms improving. He also stresses: “Prebiotics, or indeed any dietary supplements, are unlikely to replace the drugs used for the treatment of psychiatric illnesses. But they might be useful in helping medication work better in people who do not respond very well to them.”

Should the worried well be hitting the prebiotics? “More studies are needed to test if they are a quick fix for brain disorders per se,” he says. “But if someone is unwell or feeling down from a cold, because the bacteria modulate the immune system, a quick fix would be prebiotics.” People hate hearing it, he says, but supplements can’t replace a healthy, varied diet. Lentils, asparagus and jerusalem artichokes are examples of natural prebiotic sources. “But who wants to eat a bowl of jerusalem artichokes when you can just pour some prebiotic powder on your cornflakes or on top of your McDonald’s?”

This year, the health journalist Michael Mosley tested the sleep-enhancing effects of prebiotics for his documentary The Truth About Sleep, and Burnet oversaw the five-day experiment. At the start of the trial, Mosley spent 21% of his time in bed awake – by the end that had shrunk to 8%. Of all the strategies Mosley tested to treat his insomnia, he found prebiotics the most effective. Bimuno promptly sold out.

“I’m still getting people asking if I want to do a full-scale study and wanting to be a participant, or saying after trying Bimuno, ‘I’ve never slept better in all my life,’” says Burnet. But after getting the Mosley thumbs-up, the company has no need to fund a study. “A bit of a bummer,” says Burnet. “I don’t know if it really works or if it’s mass hysteria.”

There have been further suggestions that the microbiome could also be the key to athletic ability. The APC Microbiome Institute in Cork published a paper in 2014 reporting its findings that the gut flora of the Ireland rugby team was more diverse than that of a healthy control group. So will people in future follow Peterson’s example and experiment with faecal transplants from top athletes? It’s not something you can do at home. The donor’s blood and stool needs to be screened for disease before being expertly delivered to the colon via a colonscope. Sedation is required. The trouble with faecal transplants, says Orla O’Sullivan, one of the APC researchers, is “you just don’t know what you’re transferring. If the donor has some undiagnosed mental health issue, then that’s what you’re going to be getting in your poo.” She mentions companies that are developing “artificial poop”, as a safer option that is more likely to be approved by health authorities. “A definite angle for this could be identifying probiotics that are elevated in athletes and that are obviously giving them some benefit, and putting them into products, whether it be for other athletes or the general public.”

The advantage of a faecal transplant is that you are inserting a ready-made microbiome into your gut, whereas oral supplements can’t be guaranteed to take up residence, and usually contain only one or a few strains. To make long-term changes to your gut flora, however, faecal transplants cannot work alone. With a bad diet, sedentary lifestyle or a dose of antibiotics, chances are your gut flora will be stripped of its diversity. As Jane A Foster, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioural neurosciences at McMaster University, Ontario, says: “The microbiome is partly driven by our own genetics, partly by environmental factors – stress, diet, age, gender. All these things affect the composition and they probably also affect the function of the bacteria that are there.”

Enders thinks it’s only a matter of time before bacteria supplements are available to support weight loss. Bacteria associated with leanness and obesity have already been identified (if you give mice bacteria from an obese human, the mice will become obese too; and if you give mice bacteria from a lean human, they will stay lean). And the common Lactobacillus reuteri increases levels of leptin, a hormone that makes you feel full up, while lowering the hunger hormone ghrelin. The bacteria could even be controlling our appetites, sending amino acids to our brains to trigger dopamine and serotonin rewards when we give them a treat.

In her book, Enders writes that multiple studies “have shown that satiety-signal transmitters increase considerably when we eat the foods that our bacteria prefer”. That is not to say, she warns, that “other aspects of weight gain should be put aside, but it could be a great additional help”.

It’s interesting that, even though there’s more work to be done, gut experts pay heed to current hypotheses in their personal lives. Enders, who analysed her healthy 97-year-old grandma’s stool out of scientific curiosity, says: “If I had a disease that research linked one specific bacteria to, I would still want to know if I had it. Like Prevotella copri with rheumatism or Acinetobacter baumannii with multiple sclerosis. But it is unclear if tackling this would help after the disease is already happening.”

Foster, who is working towards using the gut microbiome as a biomarker for predicting and diagnosing mental health problems, says she doesn’t take probiotic supplements (“I am stress-free, resilient, high-energy – I don’t need one”), although “probioticking” is a verb in her household. “I have two adolescents, a 16- and a 19-year-old. I probiotic them both at times. If one is feeling under the weather, she does a three-week probiotic course along with extra vitamins. She already has a fabulous diet, but if you feel a little bit down, sure, I would completely recommend it.”

They are all keen to point out, however, that no matter how repetitive the advice, and difficult to achieve in the west, a varied diet rich in fresh vegetables and fermented foods such as sauerkraut, along with exercise and stress management, is the route to sustained gut (and general) health.

Cryan’s official line is that we are five years off cracking the human gut microbiome, but of course there’s no way of knowing. Could it be a similar case to that of the human genome – another great hope in predicting disease and personalised preventative medicine, but which becomes more impenetrably complex the more we learn about it? “It could be,” he admits. “The only difference is that, unlike your genome, which you can’t do an awful lot with, your microbiome is potentially modifiable.”

Enders agrees. “I think the belief that many or even all diseases are rooted in only the gut bacteria will have to turn out as wrong,” she says. “Humans are wonderfully complex animals with multiple connections to mind, food, life and the environment. The cool thing is that it is far easier to change the gut compared with our genes.”

The Psychobiotic Revolution: Mood, Food and the New Science of the Gut-Brain Connection will be published on 30 November by National Geographic (£17.99). To order a copy for £15.29 go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846. Free UK p&p over £10, online orders only. Phone orders min p&p of £1.99.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion