Found 10 results for boys

Shannon Hale

Life is short, so live extra lives. Read books.

After reading my post about boys shamed for wanting to read “girl” books, a teacher emailed me this experience.

“One of my colleagues at work shared on facebook a blogpost you wrote about giving a reading at a school and the principal had decided that the author of’ The Princess Academy’ would only draw the interest of female students. I loved what you wrote, and it reminded me so clearly of something I experienced at [high school name redacted] – in IB English of all places! – that I HAD to write to you. I was astounded when several male students in IB English – in the mid-90s – opted out of all reading of Jane Austen. I’m sure we were reading “Pride and Prejudice” and it fit into some theme we were reading in World Lit. The young men who just chose not to read and not participate in discussions (etc) were superb, straight-A students, that kind. But they had already decided that this was girly stuff and their masculinity was not going to have to suffer through that. I reminded them that all the young women in the class had made their way through ‘David Copperfield’ and a myriad of male-narrated works, but it made no difference. Stubborn, stubborn, stubborn. Of course, during the most stubborn student’s IB oral exam, I lifted an eyebrow and asked him a follow-up question about Austen’s work, and he put together something garnered from class discussions.

…

It’s a deep issue – the common male refusal to empathize with a female character, as some kind of attack on masculinity, while women are all the time stretching empathy muscles to understand all the characters (in general, I think – a fascinating area of prejudice and fear that lingers long past the discussion of equal rights).”

No Boys Allowed: School visits as a woman writer

I’ve been doing school visits as part of my tour for PRINCESS ACADEMY: The Forgotten Sisters. All have been terrific–great kids, great librarians. But something happened at one I want to talk about. I’m not going to name the school or location because I don’t think it’s a problem with just one school; it’s just one example of a much wider problem.

This was a small-ish school, and I spoke to the 3-8 grades. It wasn’t until I was partway into my presentation that I realized that the back rows of the older grades were all girls.

Later a teacher told me, “The administration only gave permission to the middle school girls to leave class for your assembly. I have a boy student who is a huge fan of SPIRIT ANIMALS. I got special permission for him to come, but he was too embarrassed.”

“Because the administration had already shown that they believed my presentation would only be for girls?”

“Yes,” she said.

I tried not to explode in front of the children.

Let’s be clear: I do not talk about “girl” stuff. I do not talk about body parts. I do not do a “Your Menstrual Cycle and You!” presentation. I talk about books and writing, reading, rejections and moving through them, how to come up with story ideas. But because I’m a woman, because some of my books have pictures of girls on the cover, because some of my books have “princess” in the title, I’m stamped as “for girls only.” However, the male writers who have boys on their covers speak to the entire school.

This has happened a few times before. I don’t believe it’s ever happened in an elementary school–just middle school or high school.

I remember one middle school 2-3 years ago that I was going to visit while on tour. I heard in advance that they planned to pull the girls out of class for my assembly but not the boys. I’d dealt with that in the past and didn’t want to be a part of perpetuating the myth that women only have things of interest to say to girls while men’s voices are universally important. I told the publicist that this was something I wasn’t comfortable with and to please ask them to invite the boys as well as girls. I thought it was taken care of. When I got there, the administration told me with shrugs that they’d heard I didn’t want a segregated audience but that’s just how it was going to be. Should I have refused? Embarrassed the bookstore, let down the girls who had been looking forward to my visit? I did the presentation. But I felt sick to my stomach. Later I asked what other authors had visited. They’d had a male writer. For his assembly, both boys and girls had been invited.

I think most people reading this will agree that leaving the boys behind is wrong. And yet–when giving books to boys, how often do we offer ones that have girls as protagonists? (Princesses even!) And if we do, do we qualify it: “Even though it’s about a girl, I think you’ll like it.” Even though. We’re telling them subtly, if not explicitly, that books about girls aren’t for them. Even if a boy would never, ever like any book about any girl (highly unlikely) if we don’t at least offer some, we’re reinforcing the ideology.

I heard it a hundred times with Hunger Games: “Boys, even though this is about a girl, you’ll like it!” Even though. I never heard a single time, “Girls, even though Harry Potter is about a boy, you’ll like it!”

The belief that boys won’t like books with female protagonists, that they will refuse to read them, the shaming that happens (from peers, parents, teachers, often right in front of me) when they do, the idea that girls should read about and understand boys but that boys don’t have to read about girls, that boys aren’t expected to understand and empathize with the female population of the world….this belief directly leads to rape culture. To a culture that tells boys and men, it doesn’t matter how the girl feels, what she wants. You don’t have to wonder. She is here to please you. She is here to do what you want. No one expects you to have to empathize with girls and women. As far as you need be concerned, they have no interior life.

At this recent school visit, near the end I left time for questions. Not one student had a question. In 12 years and 200-300 presentations, I’ve never had that happen. So I filled in the last 5 minutes reading them the first few chapters of The Princess in Black, showing them slides of the illustrations. BTW I’ve never met a boy who didn’t like this book.

After the presentation, I signed books for the students who had pre-ordered my books (all girls), but one 3rd grade boy hung around.

“Did you want to ask her a question?” a teacher asked.

“Yes,” he said nervously, “but not now. I’ll wait till everyone is gone.”

Once the other students were gone, three adults still remained. He was still clearly uncomfortable that we weren’t alone but his question was also clearly important to him. So he leaned forward and whispered in my ear, “Do you have a copy of the black princess book?”

It broke my heart that he felt he had to whisper the question.

He wanted to read the rest of the book so badly and yet was so afraid what others would think of him. If he read a “girl” book. A book about a princess. Even a monster-fighting superhero ninja princess. He wasn’t born ashamed. We made him ashamed. Ashamed to be interested in a book about a girl. About a princess–the most “girlie” of girls.

I wish I’d had a copy of The Princess in Black to give him right then. The bookstore told him they were going to donate a copy to his library. I hope he’s brave enough to check it out. I hope he keeps reading. I hope he changes his own story. I hope all of us can change this story. I’m really rooting for a happy ending.

Stories for all

A school librarian introduces me before I give an assembly. “Girls, you’re in for a real treat. You will love Shannon Hale’s books. Boys, I expect you to behave anyway.”

I’m being interviewed for a newspaper article/blog post/pod cast, etc. They ask, “I’m sure you’ve heard about the crisis in boys’ reading. Boys just aren’t reading as much as girls are. So why don’t you write books for boys?”

Or, “Why do you write strong female characters?” (and never asked “Why do you write strong male characters?”)

At book signings, a mother or grandmother says, “I would buy your books for my kids but I only have boys.”

Or, “My son reads your books too—and he actually likes them!”

Or, a dad says, “No, James, let’s get something else for you. Those are girl books.”

A book festival committee member tells me, “I pitched your name for the keynote but the rest of the committee said ‘what about the boys?’ so we chose a male author instead.”

A mom has me sign some of my books for each of her daughters. Her 10-year-old son lurks in the back. She has extra books that are unsigned so I ask the boy, “Would you like me to sign one to you?” The mom says, “Yeah, Isaac, do you want her to put your name in a girl book?” and the sisters all giggle. Unsurprisingly, Isaac says no.

These sorts of scenarios haven’t happened just once. They have been my norm for the past twelve years. I’ve heard these and many more like them countless times in every state I’ve visited.

In our culture, there are widespread assumptions:

1. Boys aren’t going to like a book that stars a girl. (And so definitely won’t like a book that stars a girl + is written by a woman + is about a PRINCESS, the most girlie of girls).

2. Men’s stories are universal; women’s stories are only for girls.

But the truth is that none of that is truth. In my position, not only have I witnessed hundreds examples of adults teaching boys to be ashamed of and avoid girls’ stories, I’ve also witnessed that boys can and do love stories about girls just as much as about boys, if we let them. For example, I’ve heard this same thing over and over again from teachers who taught Princess Academy: “When I told the class we were going to read PRINCESS ACADEMY the girls went 'Yay!’ and the boys went 'Boo!’ But after we’d read it the boys liked it as much or even more than the girls.”

Most four-year-old boys will read THE PRINCESS IN BLACK without a worry in the world. Most fourth grade boys won’t touch PRINCESS ACADEMY—at least if others are watching. There are exceptions, of course. I’ve noticed that boys who are homeschooled are generally immune. My public-school-attending 11-year-old son’s favorite author is Lisa McMann. He’s currently enjoying Kekla Magoon’s female-led SHADOWS OF SHERWOOD as much as he enjoyed the last book he read: Louis Sachar’s boy-heavy HOLES. But generally in the early elementary years, boys learn to be ashamed to show interest in anything to do with girls. We’ve made them ashamed.

I want to be clear; if there’s a boy who only ever wants to read about other boys, I think that’s fine. But I’ve learned that most kids are less interested in the gender of the main character and more interested in the kind of book—action, humor, fantasy, mystery, etc. In adults’ well-meant and honest desire to help boys find books they’ll love, we often only offer them books about boys. We don’t give them a chance.

Whenever I speak up about this, I am accused of trolling for boy readers when they aren’t my “due.” So let me also be clear: I have a wonderful career. I have amazing readers. I am speaking up not because I’m disgruntled or demand that more boys read my books but because my particular career has put me in a position to observe the gender bias that so many of us have inherited from the previous generations and often unknowingly lug around. I’ve been witnessing and cataloging widespread gender bias and sexism for over a decade. How could I face my kids if I didn’t speak up?

And here’s what I’ve witnessed: “great books for boys” lists, books chosen for read alouds, and assigned reading in high schools and colleges, etc. are overwhelmingly about boys and written by men. Peers (and often adults) mock and shame boys who do read books about girls. Even informed adults tend to qualify recommendations that boys hear very clearly. “Even though this stars a girl, boys will like it too!”

This leads to generations of boys denied the opportunity of learning a profound empathy for girls that can come from reading novels. Leads to a culture where boys feel perfectly fine mocking and booing things many girls like and adults don’t even correct them because “boys will be boys.” Leads to boys and girls believing “girlie” is the gravest insult, that girls are less significant, not worth your time. Leads to girls believing they must work/learn/live “like a man” in order to be successful. Leads to boys growing into men who believe women are there to support their story, expect them to satisfy men’s desires and have none of their own.

The more I talk about this topic, the more I’m amazed at how many people haven’t really thought about it or considered the widespread effect gendered reading causes. I was overwhelmed by the response to a blog post I wrote earlier this year. To carry on this conversation, I’m working with Bloomsbury Children’s Books to create #StoriesForAll. Each day this week we’ll feature new essays on this topic from authors, parents, teachers, librarians, booksellers, and readers. On twitter, instagram, and tumblr, join us with the #StoriesForAll hashtag to share experiences, photos, book recommendations. Discuss: How deep is the assumption that there are boy books and girl books? Does it matter? What have you witnessed with regards to gendered reading? What damage does gendered reading cause to both girls and boys? What can each of us do to undo the damage and start making a change?

I yearn for that change. For our girls and for our boys.

——————

Shannon Hale is the New York Times bestselling author of over 20 books, including the Ever After High trilogy and the Newbery Honor winner Princess Academy. She co-wrote The Princess in Black series and Rapunzel’s Revenge with her husband, author Dean Hale. They have four children.

Books connect far-away family

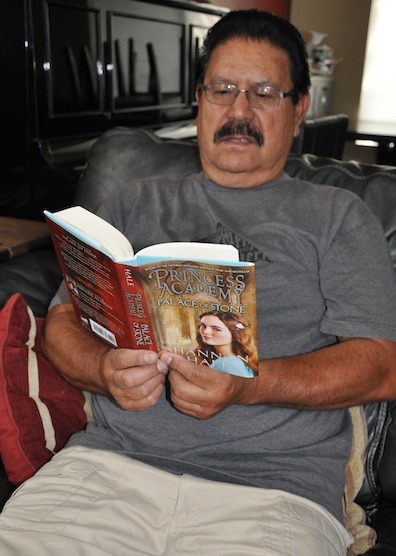

I want to tell you a quick story, with permission from who told it to me, of the unexpected ways books connect us. A few years ago I did a photographic essay of men and boys reading Princess Academy to illustrate that, yes, this does happen and yes, it is okay for heaven’s sake. One of the participants is this man, who I’ve known for years:

He is a family man. He has many children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren and is hands-on involved in their lives in an active, loving manner. He’s a treasure. A few years ago one of his grandchildren gave up her two precious children for adoption. As is often the case, even though it was for the best, it was still very hard for the whole family.

The two kids, a brother and sister, joined a loving family. And not knowing that their birth grandparents knew me, they apparently became fans of my books. One day the grandson is reading through my past blog posts and sees the above picture. He recognizes “Papa.” And so the boy has his mother take a picture of him reading Princess Academy in the same manner, recreating the photo. His adoptive mother sends the picture to his birth mother, who shows the birth grandparents. And today, with tears, they showed it to me.

Re: boys shamed for reading “girl” books

I’m loving the conversations going on re: my last post. Here are a few:

From Delicious Cake

I’ve always thought that a majority of the so-called differences between men and women are largely cultural constructs. (Even differences that are considered innate, like brain structure. We are treated differently from the moment of birth, different things are expected of us—just think of the effect that can have on a developing brain). Stories like this author’s point not only to our culture’s different expectations of boys and girls, but to its lingering misogyny as well. When a girl likes “boy things” it is often seen as a sign of strength and independence, and is encouraged. When a boy likes “girl things”? It is a sign of weakness and needs to be stomped out.

Growing up as a “tomboy” (with a sweet Fisher-Price plastic tool set that my parents totally let me use to hammer real nails) I never felt any shame for my interests. They were a source of strength in a difficult childhood. But the boys I knew who showed any interest in toys or activities that were deemed feminine were ridiculed and humiliated. It made them targets. Masculinity is celebrated in our culture. Femininity is a weakness that must be overcome.

Revolt. Revolt, every child. Find what it is you are and embrace it. We are the librarians, and we will fight for your right to grow.

And to add onto that, it leads boys to start making fun of “girl things” to defend themselves- to clutch at weak reasons for why they’re denied these things.

They reason it’s denied because it’s bad, and because it’s a “girl thing,” and in this way, simply, irreversibly, “girl things” become “bad things.”

It’s weird because even as a girl, in elementary school “girly” things were pretty much shunned. And anyone acting “girly” was also shunned. I grew up with this idea and to this day can’t stand anyone calling me “girly” or doing “girly” things. It’s not bad to be a tomboy, but I don’t think it’s right to say that acting like a girl is bad.

I just generally dislike that “girly” is bad and “manly” is good. Doesn’t make sense to me.

And the message that media sends when it says “We can’t have a female lead because women identify with male leads, but men don’t identify with female leads” is that men are such craven failures of people that they can’t identify with another human being because of sex bits and a skirt. It is also saying that women are less than men: that a male character can transcend boundaries in his humanity, in his worth. But a female character is first and foremost a female, the sex-class, the lesser half, and fundamentally inscrutable to men.

And in that way it contributes to sexism; because men simply can’t understand women because they are so different and so much less. And that contributes to violence on women, because when there is a they and it is okay, it is encouraged, it is required to think of them as other and not quite the same, not quite human, it becomes okay to hurt them.

We don’t live in a void; media does not come from nowhere; everything is linked; all roads intersect one other.

We’re Ready: a post for #kidlitwomen

I was presenting an assembly for kids grades 3-8 while on book tour for the third PRINCESS ACADEMY book.

Me: “So many teachers have told me the same thing. They say, ‘When I told my students we were reading a book called PRINCESS ACADEMY, the girls said—’”

I gesture to the kids and wait. They anticipate what I’m expecting, and in unison, the girls scream, “YAY!”

Me: “'And the boys said—”

I gesture and wait. The boys know just what to do. They always do, no matter their age or the state they live in.

In unison, the boys shout, “BOOOOO!”

Me: “And then the teachers tell me that after reading the book, the boys like it as much or sometimes even more than the girls do.”

Audible gasp. They weren’t expecting that.

Me: “So it’s not the story itself boys don’t like, it’s what?”

The kids shout, “The name! The title!”

Me: “And why don’t they like the title?”

As usual, kids call out, “Princess!”

But this time, a smallish 3rd grade boy on the first row, who I find out later is named Logan, shouts at me, “Because it’s GIRLY!”

The way Logan said “girly"…so much hatred from someone so small. So much distain. This is my 200-300th assembly, I’ve asked these same questions dozens of times with the same answers, but the way he says "girly” literally makes me take a step back. I am briefly speechless, chilled by his hostility.

Then I pull it together and continue as I usually do.

“Boys, I have to ask you a question. Why are you so afraid of princesses? Did a princess steal your dog? Did a princess kidnap your parents? Does a princess live under your bed and sneak out at night to try to suck your eyeballs out of your skull?”

The kids laugh and shout “No!” and laugh some more. We talk about how girls get to read any book they want but some people try to tell boys that they can only read half the books. I say that this isn’t fair. I can see that they’re thinking about it in their own way.

But little Logan is skeptical. He’s sure he knows why boys won’t read a book about a princess. Because a princess is a girl—a girl to the extreme. And girls are bad. Shameful. A boy should be embarrassed to read a book about a girl. To care about a girl. To empathize with a girl.

Where did Logan learn that? What does believing that do to him? And how will that belief affect all the girls and women he will deal with for the rest of his life?

At the end of my presentation, I read aloud the first few chapters of THE PRINCESS IN BLACK. After, Logan was the only boy who stayed behind while I signed books. He didn’t have a book for me to sign, he had a question, but he didn’t want to ask me in front of others. He waited till everyone but a couple of adults had left. Then, trembling with nervousness, he whispered in my ear, “Do you have a copy of that black princess book?”

He wanted to know what happened next in her story. But he was ashamed to want to know.

Who did this to him? How will this affect how he feels about himself? How will this affect how he treats fellow humans his entire life?

We already know that misogyny is toxic and damaging to women and girls, but often we assume it doesn’t harm boys or men a lick. We think we’re asking them to go against their best interest in the name of fairness or love. But that hatred, that animosity, that fear in little Logan, that isn’t in his best interest. The oppressor is always damaged by believing and treating others as less than fully human. Always. Nobody wins. Everybody loses.

We humans have a peculiar tendency to assume either/or scenarios despite all logic. Obviously it’s NOT “either men matter OR women do.” It’s NOT “we can give boys books about boys OR books about girls.” It’s NOT “men are important to this industry OR women are."

It’s not either/or. It’s AND.

We can celebrate boys AND girls. We can read about boys AND girls. We can listen to women AND men. We can honor and respect women AND men. And And And. I know this seems obvious and simplistic, but how often have you assumed that a boy reader would only read a book about boys? I have. Have you preselected books for a boy and only offered him books about boys? I’ve done that in the past. And if not, I’ve caught myself and others kind of apologizing about it. "I think you’ll enjoy this book EVEN THOUGH it’s about a girl!” They hear that even though. They know what we mean. And they absorb it as truth.

I met little Logan at the same assembly where I noticed that all the 7th and 8th graders were girls. Later, a teacher told me that the administration only invited the middle school girls to my assembly. Because I’m a woman. I asked, and when they’d had a male author, all the kids were invited. Again reinforcing the falsehood that what men say is universally important but what women say only applies to girls.

One 8th grade boy was a big fan of one of my books and had wanted to come, so the teacher had gotten special permission for him to attend, but by then he was too embarrassed. Ashamed to want to hear a woman speak. Ashamed to care about the thoughts of a girl.

A few days later, I tweeted about how the school didn’t invite the middle school boys. And to my surprise, twitter responded. Twitter was outraged. I was blown away. I’ve been talking about these issues for over a decade, and to be honest, after a while you feel like no one cares.

But for whatever reason, this time people were ready. I wrote a post explaining what happened, and tens of thousands of people read it. National media outlets interviewed me. People who hadn’t thought about gendered reading before were talking, comparing notes, questioning what had seemed normal. Finally, finally, finally.

And that’s the other thing that stood out to me about Logan—he was so ready to change. Eager for it. So open that he’d started the hour expressing disgust at all things “girly” and ended it by whispering an anxious hope to be a part of that story after all.

The girls are ready. Boy howdy, we’ve been ready for a painful long time. But the boys, they’re ready too. Are you?

I’ve spoken with many groups about gendered reading in the last few years. Here are some things that I hear:

A librarian, introducing me before my presentation: “Girls, you’re in for a real treat. You’re going to love Shannon Hale’s books. Boys, I expect you to behave anyway.”

A book festival committee member: “Last week we met to choose a keynote speaker for next year. I suggested you, but another member said, 'What about the boys?’ so we chose a male author instead.”

A parent: “My son read your book and he ACTUALLY liked it!”

A teacher: “I never noticed before, but for read aloud I tend to choose books about boys because I assume those are the only books the boys will like.”

A mom: “My son asked me to read him The Princess in Black, and I said, 'No, that’s for your sister,’ without even thinking about it.”

A bookseller: “I’ve stopped asking people if they’re shopping for a boy or a girl and instead asking them what kind of story the child likes.”

Like the bookseller, when I do signings, I frequently ask each kid, “What kind of books do you like?” I hear what you’d expect: funny books, adventure stories, fantasy, graphic novels. I’ve never, ever, EVER had a kid say, “I only like books about boys.” Adults are the ones with the weird bias. We’re the ones with the hangups, because we were raised to believe thinking that way is normal. And we pass it along to the kids in sometimes overt (“Put that back! That’s a girl book!”) but usually in subtle ways we barely notice ourselves.

But we are ready now. We’re ready to notice and to analyze. We’re ready to be thoughtful. We’re ready for change. The girls are ready, the boys are ready, the non-binary kids are ready. The parents, librarians, booksellers, authors, readers are ready. Time’s up. Let’s make a change.

Why boys don’t read girls (sometimes)

When I do book signings, most of my line is made up of young girls with their mothers, teen girls alone, and mother friend groups. But there’s usually at least one boy with a stack of my books. This boy is anywhere from 8-19, he’s carrying a worn stack of the Books of Bayern, and he’s excited and unashamed to be a fan of those books. As I talk to him, 95% of the time I learn this fact: he is home schooled.

There’s something that happens to our boys in school. Maybe it’s because they’re around so many other boys, and the pressure to be a boy is high. They’re looking around at each other, trying to figure out what it means to be a boy–and often their conclusion is to be “not a girl.” Whatever a girl is, they must be the opposite. So a book written by a girl? With a girl on the cover? Not something a boy should be caught reading.

But something else happens in school too. Without even meaning to perhaps, the adults in the boy’s life are nudging the boy away from “girl” books to “boy” books. When I go on tour and do school visits, sometimes the school will take the girls out of class for my assembly and not invite the boys. I talk about reading and how to fall in love with reading. I talk about storytelling and how to start your own story. I talk about things that aren’t gender-exclusive. But because I’m a girl and there are girls on my covers, often I’m deemed a girl-only author. I wonder, when a boy author goes to those schools with their books with boys on the covers, are the girls left behind? I want to question this practice. Even if no boy ever really would like one of my books, by not inviting them, we’re reinforcing the wrong and often-damaging notion that there’s girls-only stuff and you aren’t allowed to like it.

I hear from teachers that when they read Princess Academy in class (by far the most girlie-sounding of all my books) that the boys initially protest but in the end like it as much as the girls, or as one teacher told me recently, “the boys were even bigger fans than the girls.”

Another staple in my signing line is the family. The mom and daughters get their books signed, and the mom confides in me, “My son reads your books on the sly” or “My son loves your books too but he’s embarrassed to admit it.” Why are they embarrassed? Because we’ve made them that way. We’ve told them in subtle ways that, in order to be a real boy, to be manly, they can’t like anything girls like.

Though sometimes those instructions aren’t subtle at all. Recently at a signing, a family had all my books. The mom had me sign one of them for each of her children. A 10-year-old boy lurked in the back. I’d signed some for all the daughters and there were more books, so I asked the boy, “Would you like me to sign one to you?” The mom said, “Yeah, Isaac, do you want her to put your name in a girl book?” and the sisters all giggled.

As you can imagine, Isaac said no.

Boos for girls

I don’t know how many school assemblies I’ve done over the past 12 years. 200-300 is my best guess. Something I’ve found is that boys feel okay booing and mocking things they see as “for girls” but that girls never mock the “boy” things. Here’s an example. This exact scenario has repeated at every elementary and middle school assembly I’ve done in the past year and a half - at least 30, maybe more, in over a dozen states.

Me: I went to Mattel headquarters. Mattel is the largest toy maker in the world. They make Thomas the Train, Justice League Figures, Matchbox Cars–

Boys: Yay!

Me: Barbie–

Boys: BOO!!!

Me: I was going to write a book for their new toy line, but it was so secret, we had to put in a security code to go down a secret hallway, into a second locked door where on a table under a shroud they had the prototypes for the new toys. I lifted the shroud and this is what I saw: (switches to slide of Ever After High dolls)

Girls: Yay!

Boys: BOOO!!! BOOOO!!!

Notice the girls did not boo Thomas or Justice League or cars. Many cheered those things too. But the boys booed Barbe and EAH in unison, loudly, as if it was only natural, expected.

I’ve put up with it for awhile. And all this booing is after I’ve even talked with the kids about how unfair it is that people claim there are boy books and girl books. How untrue. Why can girls read anything but boys are told that they can only read half the books? And we’ve talked frankly about this. Still, the loud, fearless, angry mocking of any mention of “girl” media.

I’ve stopped putting up with it. When they boo, I stop them now. I demand respect. “I don’t know who told you it was okay to boo anything that you think girls like, but it’s not okay with me. That will stop. Girls, you don’t have to put up with that. The things you like deserve respect. You deserve respect.” I don’t know if they listen. But I’m going to say it all the same.

I think that by being “polite” and pretending to ignore the boos, I was actually reinforcing their opinion that this was okay. Tolerating something out of civility sure looks like complicity if you’re a girl in the audience. I won’t be complicit anymore. Which is “kinder”: ignoring the boos or calling them on it?

They say boys won’t read “girl” books. Pbbth! Some photos from my blog post, “Real men read Princess Academy.” Send me your photos of a guy reading a book about/by a girl to enter the contest!

Stories for all: author Jon Scieszka

Shannon’s idea of Stories For All is absolutely fantastic … and absolutely vital.

Fifteen years after founding Guys Read (a web-based literacy initiative for boys at www.guysread.com) in response to the dismal underachievement of boys in reading, I still get questions that let me know we have a long way to go in understanding the role gender might play in reading. And a long way to go in using this understanding to help kids become real readers.

I get questions like:

1. “Why do you have women authors in the Guys Read story collections?”

2. “What should I put in a book if I want to write for boys?”

3. “Why don’t you like girls?”

One of the primary goals of Guys Read is to promote a discussion of gender and reading – how gender might effect reading, how our assumptions about gender might effect reading. Maybe the answers I try to give to these questions can help add to our Stories For All discussion.

1. The Guys Read story collections are original short stories, grouped by genre, by some of the best writers in kids’ books. So OF COURSE they would have women authors.

Boys can, and should read writing by men and women.

Check out this amazing bunch of authors who have contributed to the first six volumes: Kate DiCamillo, Margaret Peterson Haddix, Gennifer Choldenko, Jackie Woodson, Anne Ursu, Shannon Hale, Rebecca Stead, Candace Fleming, Sy Montgomery, Elizabeth Partridge, Thanhha Lai, Lisa Brown, Adele Griffin, Claire Legrand, Rita Williams-Garcia, Kelly Barnhill, and Nikki Lofton.

Who wouldn’t want to read those authors?

And yes, girls can read the Guys Read books too.

2. No one should be writing for boys. Or writing for girls. Please don’t do that.

Our job as authors is to write the best stories we can, and maybe help those stories find their best readers.

If that reader happens to be a boy – great!

If that reader happens to be a girl – great!

3. Efforts to help boys are not efforts to hurt girls.

Literacy is not a zero-sum proposition. Good things we do for boys can make a better reading world for girls.

The more literate any citizen is, the better off we all are.

While working as our first National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, my platform was “Reaching Reluctant Readers”. Visiting schools, speaking at conventions, presenting at libraries, I quickly found that what we had learned about reaching reluctant boy readers applies to every reader. Here are some tips and strategies we can all try. For every reader.

– expand the definition of “reading” to include non-fiction, graphic novels, or genres like sci-fi, even if you personally don’t particularly enjoy them

– allow readers a chance for choice. Their choice.

– treat every reader as an individual.

And most importantly

– raise awareness about gender issues and reading.

Suspend quick judgment and blame, and have a discussion.

What I love most about Stories For All is Shannon’s call to hear from the experts – teachers, librarians, booksellers, moms, dads, and the kids themselves. This is not a test with a simple right answer or a wrong answer. It’s a discussion, a process, a chance to make a change for better reading for all.

Let’s.

———————-

Jon Scieszka is the award-winning and bestselling author of a boatload of books, including The True Story of the Three Little Pigs!, The Stinky Cheese Man, the Time Warp Trio series, the Trucktown series, and the Frank Einstein series. He was the USA’s first National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature and is the founder of Guys Read. Jon lives in Brooklyn with his wife. They have two children.