Earlier this decade the artist Theaster Gates began dropping hints that he might not be long for the confines of the art world. Instead, Gates said, he wanted to focus on what he called “practicing life”. What could be interpreted as an abstract idea made sense when you look at Gates’s work, most prominently a series of project spaces in South Side Chicago that located art outside the walls of galleries and institutions.

In the African American neighborhood south of the Midway, Gates gutted a string of condemned buildings and then turned them into sculpture, covertly turning his collectors into patrons of urban renewal. “If you draw a circle around a thing, stand in the middle of the thing, invite others to stand in it with you and pray and work and move your body, that place won’t be the same any more,” he says of the project.

He took former crack houses and turned them into cinemas, showing everything from Mario Van Peebles’s back catalog to Car Wash. Under his guidance, a crumbling bank became a center for art and held dance classes. Along with Turner prize winners Assemble, he’s at the heart of a new way of thinking of regeneration as art itself.

It is a time-honored role for artist as designator, to point at the stuff of the physical world and revision it as art, harkening back to the readymade. But Gates’s decision to “bump off from art” and live “in the sphere of dirt, the dirty, the stuff that we think is in the ground” was revelatory, leading to invitations to Davos and a TED Talk, where he talked about how he revived a neighborhood with imagination and hard graft. In the insistence that the scrap material framing black lives has important pedigree – and in the starkness by which Gates’s interventions with lumber and screws made refuse into investment-class commodity – was also the flat-out thrill of seeing a broken trickle system work, even but once.

Now he’s back with But To Be A Poor Race, Gates’s first show with Los Angeles gallery Regen Projects, and he is in Washington DC with an invitation to the White House in the final days of the Obama presidency. “I feel like I’m settling into my values,” says Gates, who will follow the Regen Projects show with an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. “It is a set of things that I want to explore deeply, like, where does real power come from? What does one do with power? And who’s really the poor race, and who really won?”

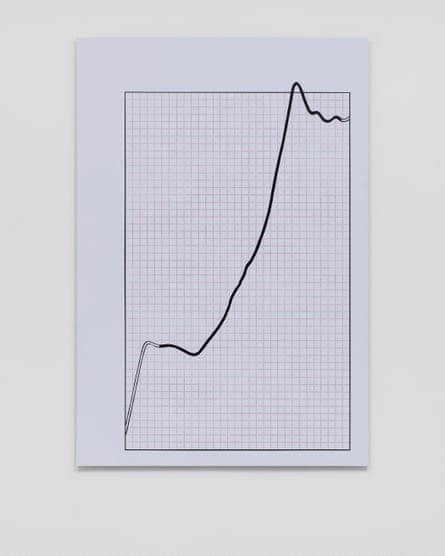

Gates’s new show takes those questions further and draws its title from the WEB DuBois book The Souls of Black Folk, and the NAACP co-founder’s line about that greatest of hardships, “but to be a poor race in the land of dollars”. Canonized as a sociologist and civil rights activist, DuBois created visualization aids for the 1900 Paris Exposition – charts showing black achievement in the 40 years after the end of the civil war. By documenting how many people owned their homes or owned land, had kitchen appliances or farm apparatuses, or went to college, DuBois and his colleagues turned statistics into unfurling lines and the blocks of color that united them. They were not only “great and handy at the thing that we know they’re great and handy at, but DuBois was an artist”, Gates says. “There was no market for his artistry except for the invention of black platforms that would elevate black people.”

Like Gates’s color-field paintings responding to DuBois’s datasets, a new suite of tar paintings made on-site in Los Angeles bind mark-making to its labors. The paintings situate black resilience and longing within the history of abstraction, when postwar artists such as Barnett Newman sought another way to confront the damage without reinforcing it through representation, lest we “become victim to it” and “believe that is ultimately the truth”, as Gates explains. “An inability to face the horrors of violence, and a desire to sing a new steadier song – abstraction, that’s what abstraction is.” Within the refusal to be literal also is the repositing of what it means to be “a byproduct of a certain poverty, a certain poorness, to use [DuBois’s] term, is an imaginative resilience that then allows people to conjure things,” Gates says.

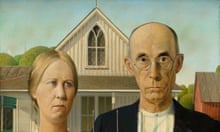

The work also confronts ideas of appropriation and imperialism head on. A bronze sculpture from a series recalling African reliquary masks in But To Be A Poor Race pulls even deeper past, heavy with the shifting weight of talismans into requisitioned modernist forms. “They were pillaging our shit,” Gates says, speaking of the modernists, who were influenced by deliberately abstracted proportions and forms in African figural carvings, often meant to represent more than one person. “As they were creating a gross poverty, a systematic poverty, they were at the same time feeding themselves the kind of black philosophy that would yield a new era of art, would bring them out of the artistic dark ages.”

“These objects for me are studies in black power. I want to be in conversation with black power,” and Gates does not mean anything as temporal as the 1960s. “I want to ask my ancestors things. Like, how did you figure out the orchestration of stars, and do it with such precision?”

When Gates travels, he says he is often asked about the violence in Chicago, and he goes instead to the lives that are “unamplified”: the “intellectual rigor, the care that black people have for one another”, he says. “Instead of just pondering it with the western rational mind, I want to get in the zone of the ecstatic, of the hallucinogenic, of the otherworldly. I want to get in the zone of the eternal. I want to be inside of those sculptural objects. I want to re-ritualize. I want to knead them so they might be a channel for power, be a protection from powers, be a hedge around my head, be the hem of Christ’s garment. I want to believe that there is power in my poverty.”

Gates, who has worked in clay and once created a fictional Japanese potter to be the ostensible author of his work in mud and water, has infused humble materials with mythology, over and again. From the roots of gospel, his band the Black Monks of Mississippi bend their voices towards something incantatory, a hum from these bodies and also beyond it. In a video at Regen Projects, Sweet Land of Liberty, the stanzas of the American patriotic anthem My Country ’Tis of Thee disintegrate in Gates’s singing of them, into the soft, fine romantic dream fragments of “we land of liberty”, “from every mountainside”, and “let freedom ring”. “They’re actually so beautiful, the kind of movement from one note to the next; they’re like salves,” he says. “It’s like Mariah Carey missing her lip-synch. All I can do is try to mouth these things. I can entertain people with the lyrics, the same way a modernist could grab an image of a big nose or a Fijian girl and put it in a painting. I could appropriate the lyric of white power, but in fact I am still just part of a poor race.”

In another clip, Gates catches the singer Yaw Agyeman coming out of a chant of devotion and overlays it with the rising intro notes of Soul Train, the long-running Chicago-born institution and “unifying mechanism” where people could gather and dance. “And so I decided to counterbalance Yaw’s nam myoho, which is a way to channel a meditative unity by using sound,” Gates says of his own filmed duet, and the shared sounds “that, in a way, don’t have meanings in and of themselves, but when done with others make meaning”. In these diverse mediums, Gates’s interrogations and redemptions of black history take visibility as pliable, and thus too are the makings of power, spun through this life and out of our attentions: “To be a poor race is a gift,” he says, “if you can see the richness.”

But To Be A Poor Race opens at Regen Projects in Los Angeles on 14 January

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion